It’s not exactly clear how Mack Mattingly first became aware of the fact that taxpayer money was going toward funding the publication of Playboy, but he didn’t like it. The Republican senator from Georgia told the House as much in 1981, specifically condemning the magazine’s salacious jokes and reader-contributed erotica.

It's not unusual for a politician to assert that such material is indecent and contributes to moral turpitude. What was unusual about Mattingly’s specific complaint was that it was directed at a version of Playboy that consisted almost entirely of blank pages. There were no pictures, no cartoons, and no nudity. The edition was produced in Braille, so by default was almost certainly the least objectionable version of the men’s magazine that could possibly be offered.

This didn’t concern Mattingly. To him, the idea of issuing a Braille Playboy was a waste of congressional funds. And for a time, he got the House of Representatives to agree. It was a sensational bit of censorship directed solely at a disadvantaged demographic. But Playboy—and the First Amendment—would not go down without a fight.

Since 1931, the Library of Congress has financially supported Braille editions of several popular magazines under their National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. Titles like Good Housekeeping, Boy’s Life, National Geographic, and a host of other magazines were and are made available for free to the visually impaired. The Library picks up the fees associated with these limited editions; in 1985, their budget was $33.8 million.

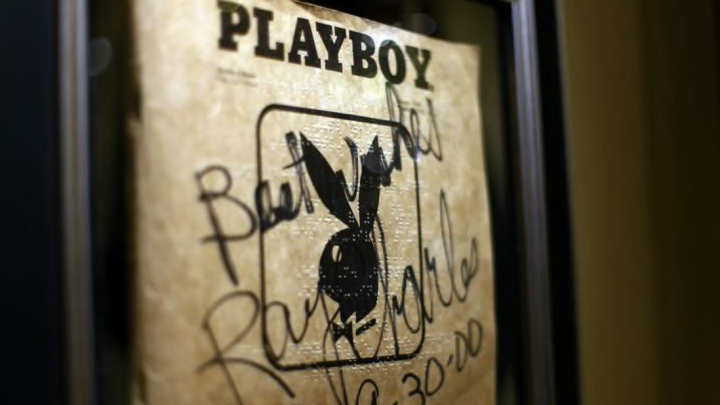

Playboy was picked up as a Braille publication beginning in 1970 and eventually became the sixth most popular periodical in the Library’s Braille magazine catalog. Most all of the content from the regular edition was included, except for the cartoons, photographs, and advertisements. Like other Braille titles, its heavy pages were closer to the density of grocery bags and embossed on both sides. It would usually be four times as many pages as an issue for a sighted audience. The only visible ink appeared on the cover, which featured the magazine’s title and familiar bunny logo.

While Playboy obviously appealed to many readers for its lurid content, the magazine also had a rich history of publishing electric journalism and short fiction from a variety of notable writers such as Ernest Hemingway, Gay Talese, and Norman Mailer. It invested thousands of words in intimate interviews with such important figures as Martin Luther King Jr., Muhammad Ali, and presidential candidates like Jimmy Carter.

Mattingly didn’t appear to have qualms with the government paying for that content to be translated. During a 1981 assembly to hash out a new budget, the senator tried to push through a proposal that would eliminate the magazine’s Party Jokes, Ribald Classics, and Playboy Forum content, arguing that translating those steamier passages was a waste of taxpayer money.

The proposal died out that night, though Congress still found time to vote in favor of giving themselves a raise to $60,662.50 a year. But Mattingly’s broaching of the topic made sure the issue began circulating in congressional hallways. Some saw the inherent silliness of it, while others worried it was flirting with censorship.

Chalmers Wylie, a Republican senator from Ohio, was on Mattingly’s side. He argued that the $103,000 of tax money spent annually on the Braille Playboy was $103,000 too much, and made it clear that he wanted the Library of Congress to scrap it entirely.

Playboy, he said, was nothing more than a way to promote "wanton and illicit sex and so forth"—which was a curious position considering the Braille version of the publication was defanged of any visually pornographic content. But one Wylie aide who spoke to the Chicago Tribune said that Wylie was "opposed to the use of federal money to subsidize the dissemination of material designed to persuade people to become promiscuous."

Playboy, the anonymous aide insisted, perpetuated that notion because the centerfold "changes in every issue and supports the notion of frequent changes of sexual partners, which is definitive of promiscuity."

Wylie was essentially arguing against a feature that wasn’t represented in the Braille edition. But on July 18, 1985, he was able to put the amendment to a vote in the House of Representatives, securing a 216-to-193 roll call win in favor of abolishing funding.

In order to get around the issue of censorship, Wylie didn't call for an outright ban on the magazine. Technically, he was pushing for a $103,000 reduction in the Library’s annual budget, which just so happened to be the exact amount earmarked for the Playboy translation.

Daniel Boorstin, the Librarian of Congress at the time, wasn't in favor of the censorship but got the message. He planned to halt production beginning in January of 1986. But Wylie’s motion antagonized two vocal and persistent groups: advocates for the blind and advocates for free speech.

In December 1985, a number of groups—the American Council of the Blind, the Blinded Veterans Association, the American Library Association, and Playboy Enterprises itself—filed a lawsuit in federal court asking a judge to overturn the ban, calling it a violation of the First Amendment.

In the complaint, the groups pointed out that Playboy had been in print for 31 years without ever once being found obscene or indecent by a state or federal court. A lawyer for Playboy, Burton Joseph, called the act "morally blind to the mandate of the First Amendment." Somewhat ironically, the move also provided a degree of indirect harm to a group of handicapped workers tasked with printing the Braille edition of Playboy. The Clovernook Center for the Blind & Visually Impaired in Cincinnati, Ohio lost the $103,000 that Congress paid annually to have the publication issued for the blind.

In an August 1986 ruling, federal district court judge Thomas Hogan declared that Congress had violated the First Amendment and called the withholding of funds a “back door method” of censorship. The Braille edition resumed publication in January 1987. Hogan ordered that the 1986 issues that had been ignored by the Library of Congress should be issued in the form of recordings.

Today, Playboy is still published in Braille, though circulation appears to have dropped from more than 1000 in 1985 to around 500 subscribers.

Undeterred by the ruling, lawmakers continued to patrol the Library of Congress for objectionable content. In 1992, newspaper columnist Roger Simon discovered that several congressman were fond of checking out one book in particular: Sex, a collection of erotic photos featuring Madonna. For educational purposes only, of course.