Victorian London was a fast-growing, sprawling metropolis. The crowded streets, ramshackle slums, and overflowing sewers meant that just walking through the city could cause sensory overload. With so many people living on top of each other, the city was thronged with bodies jostling for space—and that went for the dead, too.

According to The Lady's Newspaper, by 1849 there were 52,000 deaths each year in London, yet the total space set aside for burial only allowed for 100,000 bodies. Churches and chapels provided small graveyards—often crammed between buildings—for locals, and sometimes offered up their basements as secure burial sites, safe from the ever-present threat of body-snatchers. But it was hardly enough room.

A sanitary reformer named George Walker, nicknamed "Graveyard Walker," made it his mission to combat the cemetery overcrowding. Like others of his era, he was convinced (incorrectly) that the foul miasmas floating up from the ground—clouds of gases from decomposing bodies—were responsible for diseases like malaria and cholera. He referred to London's many burial grounds as "so many centers of foci of infection ... generating constantly the dreadful effluvia of human putrefaction." According to his research, the majority of London’s 182 parochial graveyards were unable to keep to the 136 burials per acre recommended by graveyard reformers. Many reported over 1000 burials per acre, and St John’s in Clerkenwell admitted to an amazing 3073 burials per acre.

To save space, bodies were often piled one on top of the other in vast pits, the wooden coffins tossed aside and burned for firewood. There were so many burials that in many churchyards the ground was raised considerably above street level. Unscrupulous vicars, keen to protect the burial fee each churchyard was permitted to charge for internment, found ever more ingenious ways of cramming yet more bodies into their overflowing burial grounds. And none was more unscrupulous than one of Walker's favorite targets, Baptist minister W. Howse of Enon Chapel near The Strand.

THE BODIES BELOW

Enon Chapel had opened around 1822 with rooms on the top floor for worship and teaching, and a basement assigned to burials. The space allotted for the dead in the basement was a mere 59 by 29 feet (about the size of a volleyball court), and the chapel above was separated from the burial pit by just a thin layer of creaky floorboards. The gaps in between allowed a putrid stench to waft through the chapel; worshippers reported a foul taste in their mouths after attending services, and said that clothes needed to be immediately aired or washed to get rid of the rancid smell. Insects caused a real nuisance, too: Sunday school children reported that “body bugs” blighted the school room, and worshippers complained that creepy-crawlies swarmed their hair and hats. But Howse charged considerably less for a burial space than other nearby parishes, and as a result the local poor overlooked the appalling state of the basement.

Such unsanitary conditions were not uncommon in London at the time, but by 1839, the situation at Enon Chapel had become so extreme something needed to be done. The chapel blamed the open sewers below the basement for the problems. But when representatives for the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers looked underneath the chapel, they discovered hundreds of decomposing corpses piled up, many of which had fallen into the open sewer, creating heaps of bloated, rotten remains.

Despite this gruesome discovery, the burial space wasn't closed; instead, the sewer was vaulted over to prevent the bodies from dropping into the water. Howse continued his unhygienic ways—and came up with even more nefarious methods to dispose of the bodies.

With over 500 bodies a year to bury and limited space to do it, Howse began paying workmen to dump wheelbarrows full of decayed corpses into the River Thames, thus clearing space for new burials. Besides the fact that Londoners used this water for bathing and drinking, there was the horror of the fact that body parts occasionally went astray on their way to the river, with passersby often coming into contact with the grisly detritus. On one occasion, an almost perfectly formed hand was discovered on the street where the chapel was located. It was quickly snatched away by the sexton.

Eventually, Howse just decided to speed up decomposition by pouring quicklime into the burial pit. The quicklime effectively turned the bodies to liquid, which oozed out of the pit and leached into the surrounding ground.

Enon Chapel became notorious as one of the worst of its kind across London, and numerous newspaper editorials bemoaned the unsavory state of burials there and in other church buildings. Some connected it to the cholera epidemics of the time (like the one in 1831-1832 that killed about 31,000 people across Great Britain), since it was believed that the foul gases emanating from decomposing bodies contributed to the spread of disease. Yet many churches continued to allow burials in their basements, provided the dead were interred in lead coffins.

This created a different—yet equally foul—problem. As the bodies decomposed, the coffins filled with gas and liquid, which if left too long had a nasty habit of exploding. To prevent this, the grave diggers needed to “tap” the lead coffins. As one such unfortunate described the practice to The Morning Chronicle in August 1842: “If you tap it underneath, if there is any dead water or ‘soup’ as it is called, it runs into a pail, and then it is taken or thrown into some place or another.”

DANCING ON THE DEAD

In June 1840, as reports on the unhygienic burial of bodies within churches abounded, the House of Lords Select Committee on the Health of Towns called Walker to give evidence. During the hearing, Walker frequently cited Enon Chapel as an example of the worst excesses of inner city London burials. By his account, 12,000 bodies had been crammed in the chapel's basement over 15 years—buried at a rate of about 30 a week. Pointing to the lack of regulation, Walker said, “I am quite amazed that such a place should have been permitted to exist.”

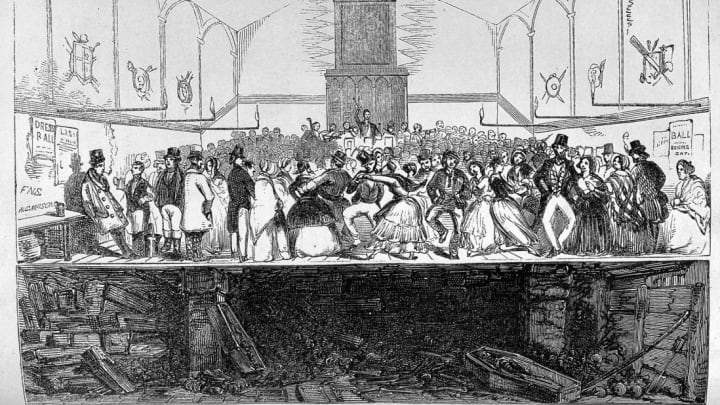

Ultimately, however, it wasn't regulation that ended the scandal at Enon Chapel—it was Howse's death in 1842. The chapel was then closed and changed hands several times before being rebranded as a temperance dance hall, even though the bodies remained buried below. The venue shamelessly played up its ghastly associations: A leaflet advertising the events read “Enon Chapel—Dancing on the Dead—Admission Threepence. No lady or gentleman admitted unless wearing shoes and stockings.”

These macabre dances—a Boxing Day gala was especially popular—continued for about four years. Around 1848, Walker managed to buy the former chapel and began exhuming the numerous bodies. He moved them to a new, peaceful resting place at the recently established West Norwood Cemetery, located seven miles from central London.

But the scandal at Enon Chapel wasn't for nothing. Public health campaigners brought the conditions there, and at locations like it, to widespread public attention, using them as evidence to force the British government to act. In 1852, Parliament passed the first in a series of Burial Acts, which prohibited burials (royalty excepted) within the city limits. This ultimately led to the closure of all burial grounds in the City of London—the historic central core of the city.

A distasteful period in London’s history had ended, and with it began a new era of grand Victorian garden cemeteries, such as Highgate and Kensal Green in Greater London. Here, burials took place in beautiful landscaped grounds far from the bustling city, where people could bury their loved ones, secure in the knowledge that the dead could rest in peace.