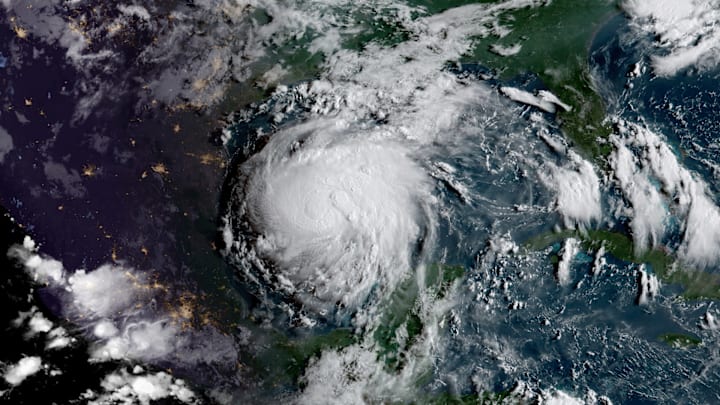

After a slow start, the 2022 hurricane season is now in full force: Hurricane Ian has roared across Cuba and is now heading straight for Florida’s west coast. At this point, we've become accustomed to hearing about hurricanes, and to predicting what sort of damage they might cause based on their category number. But how do meteorologists categorize these often-deadly storms, and how does that scale work?

First, a quick primer: Hurricanes are tropical cyclones that occur in the Atlantic Ocean and have winds with a sustained speed of at least 74 mph. A tropical cyclone, in turn, is a storm system that develops in the tropics and is characterized by a low pressure center and thunderstorms that produce strong winds, rain, and storm surges. Tropical cyclone is a generic name that refers to the storms’ geographic origin and cyclonic rotation around a central eye. Depending on their location and strength, the storms are called different things. What gets dubbed a hurricane in the Atlantic, for example, would be called a typhoon if it happened in the northwestern Pacific.

What’s the difference between a hurricane and a tropical storm?

Simply put: Wind speed. When tropical cyclones are just starting out as general areas of low pressure with the potential to strengthen, they’re called tropical depressions. They’re given sequential numbers as they form during a storm season so the National Hurricane Center (NHC) can keep tabs on them.

Once a cyclone’s winds kick up to 39 mph and sustain that speed for 10 minutes, it becomes a tropical storm and the NHC gives it a name. If the cyclone keeps growing and sustains 74 mph winds, it graduates to a hurricane.

Once we call it a hurricane, how do we categorize it?

In order to assign a numeric category value to a hurricane, meteorologists look to the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, which was developed as a classification system for Western Hemisphere tropical cyclones in the late 1960s and early ’70s by structural engineer Herbert Saffir and his friend, meteorologist Robert Simpson, who was the director of the NHC at the time.

When Saffir was working on a United Nations project to study low-cost housing in hurricane-prone areas, it struck him that there was no simple, standardized way of describing hurricanes and their damaging effects, like the way the Richter scale is used to describe earthquakes. He created a five-level scale based on wind speed and sent it off to Simpson, who expanded on it to include the effects on storm surge and flooding. Simpson began using it internally at the NHC, and then in reports shared with emergency agencies. It proved useful, so others began adopting it and it quickly spread.

How does the Saffir-Simpson scale work?

According to the NHC, the scale breaks down like this. Category 1 storms have sustained winds of 74 to 95 mph. These “very dangerous winds will produce some damage: Well-constructed frame homes could have damage to roof, shingles, vinyl siding, and gutters. Large branches of trees will snap and shallowly rooted trees may be toppled. Extensive damage to power lines and poles likely will result in power outages that could last a few to several days.”

Category 2 storms have sustained winds of 96 to 110 mph. These “extremely dangerous winds will cause extensive damage: Well-constructed frame homes could sustain major roof and siding damage. Many shallowly rooted trees will be snapped or uprooted and block numerous roads. Near-total power loss is expected with outages that could last from several days to weeks.”

Category 3 storms have sustained winds of 111 to 129 mph. This is the first category that qualifies as a “major storm” and “devastating damage will occur: Well-built framed homes may incur major damage or removal of roof decking and gable ends. Many trees will be snapped or uprooted, blocking numerous roads. Electricity and water will be unavailable for several days to weeks after the storm passes.”

Category 4 storms have sustained winds of 130 to 156 mph. These storms are “catastrophic” and damage includes: “Well-built framed homes can sustain severe damage with loss of most of the roof structure and/or some exterior walls. Most trees will be snapped or uprooted and power poles downed. Fallen trees and power poles will isolate residential areas. Power outages will last weeks to possibly months. Most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks or months.”

Finally, Category 5 storms have sustained winds of 157 mph or higher. The catastrophic damage entailed here includes: “A high percentage of framed homes will be destroyed, with total roof failure and wall collapse. Fallen trees and power poles will isolate residential areas. Power outages will last for weeks to possibly months. Most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks or months.”

Is there any hurricane worse than a Category 5?

Not on paper, but there have been hurricanes that have gone beyond the upper bounds of the scale. And that may happen more frequently in the future: The storms use warm water to fuel themselves and as ocean temperatures rise due to climate change, climatologists predict that potential hurricane intensity will increase.

Both Saffir and Simpson have said that there’s no need to add more categories because once things go beyond 157 mph, the damage all looks the same: really, really bad. Still, that hasn't stopped several scientists from suggesting that maybe the time has come to consider a Category 6 addition.

Timothy Hall, a senior scientist at The Climate Service, told the Los Angeles Times in 2018 that if the current global warming trends continue, he can foresee a time—likely by the end of the century—where wind speeds could blow past 230 mph, which could create conditions similar to a F-4 tornado (which has the power to lift cars off the ground and send them hurtling through the air with relative ease).

“If we had twice as many Category 5s—at some point, several decades down the line—if that seems to be the new norm, then yes, we’d want to have more partitioning at the upper part of the scale,” Hall said. “At that point, a Category 6 would be a reasonable thing to do.”

An earlier version of this article appeared in 2013; it has been updated for 2022.