With its inviting pastel packaging, the pink Ouija board for girls fit right in on toy shelves when it was released in 2008. The moon and sun symbols, normally depicted in a Victorian-era style, had been redesigned as generic cartoons. It came with a purse-like carrying case and cards with questions like Will I be a famous actor someday? and Who will call/text me next? From the opposite end of the game aisle, the new board could have been mistaken for Pretty Pretty Princess or Mystery Date—but it didn't fail to catch the attention of some sharp-eyed parents.

News of the product began spreading around the internet soon after its debut, with religious blogs accusing the toy's manufacturer, Hasbro, of marketing the occult to kids. There was a movement to boycott Toys "R" Us and Hasbro in 2010 because of it. "Hasbro is treating it as if it's just a game," Christian activist Stephen Phelan told Fox News. "It's not Monopoly."

But despite the sudden public reaction, Ouija boards had in fact been marketed as a game for a century by the time "Ouija for girls" hit toy stores.

Parlor Trick to Party Game

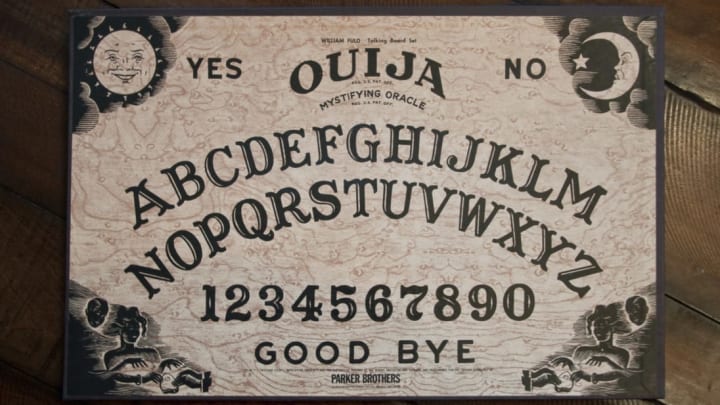

Ouija boards, or "talking boards," are a fairly recent invention. They were an outgrowth of Spiritualism, a 19th century religious movement that believed in communicating with the dead. Among other types of early technology they used to try and reach the deceased, Spiritualists would sometimes paint the alphabet onto a table and use a rolling pointer, or planchette, to spell out otherworldly messages letter by letter. Soon other elements, like a Yes and No in the top corners, the word GOODBYE at the bottom, and the numbers 0 through 9 beneath the alphabet, became standard in the design. The components were simple enough that anyone with curiosity in the supernatural could assemble their own board at home.

In 1890, three entrepreneurs named Elijah Bond, Charles Kennard, and William H.A. Maupin decided to monetize the parlor game. They secured the patent for the Ouija board (Kennard claimed the term ouija was an ancient Egyptian word for good luck) and started selling the wooden games for $1.50 a pop. Even though the board sold well, the original team dissolved after several years due to internal conflicts, and an employee of their novelty company, William Fuld, took over the rights. He was instrumental in transforming Ouija into an iconic toy brand—by the time of his passing in 1927, Fuld held over 21 Ouija-related patents and copyrights.

Fuld—and after his death, the Fuld family company—weren't afraid to play up the sense of mystery surrounding the boards in order to sell games. A 1920 advertisement in The Metropolitan magazine featured promises of a talking board that "Prophesies—Forewarns—and Prefigures, Your Destiny" beneath an eerie illustration of a disembodied face floating behind a player's shoulder—an image that would become part of the board's design. In 1938, the Fuld company sent out a mailer that read: "Call it a game if you like—laugh at the weird, uncanny messages it brings you if you dare, but you'll have to admit that mystifying Oracle Ouija gives you the most intensely interesting, unexplainable entertainment you've ever experienced."

Fascination with Spiritualism was still strong in early 20th century America, and Ouija board sales reflected that, with Fuld personally making $1 million from the game before he died in 1927. Ouija boards allowed members of the general public to dabble in mysticism without fully committing to hiring a medium. Guiding the planchette also provided a way for courting couples to touch and flirt discreetly, as Norman Rockwell's May 1920 cover for The Saturday Evening Post showed.

Investing in the New Age Movement

Ouija continued to be a money-maker for the Fuld family until it eventually caught the attention of one of America's largest toy companies. Parker Brothers bought the manufacturing rights to the Ouija board in 1966, and instead of giving it a family friendly-makeover in keeping with the other games in their stable, the board game company decided to maintain the darker marketing style that had worked for the product in the past. Boxes displayed a mysterious shrouded figure waving a hand as if casting a spell. The packaging advertised that games were made in Salem, Massachusetts—the town where Parker Brothers was founded as well as the site of America's most infamous witch trials.

The Ouija brand turned out to be a savvy purchase for Parker Brothers. The New Age movement was starting to form in the mid- to late-1960s, and the public was more interested in Spiritualism and the occult than it had been since the beginning of the century. In 1967, the year after Parker Brothers bought Ouija, the game outsold Monopoly.

Even the board's frightening appearance in 1973's The Exorcist and the Satanic Panic of the 1980s weren't enough to keep people from buying the game. By the 1980s and '90s, it had gone from a Spiritualist activity for adults to a game that kids and teenagers broke out at get-togethers. "Back then Ouija boards were still a staple of sleepover parties," Mitch Horowitz, author of the book Occult America, tells Mental Floss. "Kids gathered in basements to smoke pot and listen to Led Zeppelin IV and play with the Ouija board."

Advertisements from this period targeted kids directly. One early '90s commercial shows a group of boys asking the board questions like "Will I ever be tall enough to slam dunk?" and "Will my parents let me go to the concert?" while zany music plays in the background.

Slumber Party Staple

Hasbro acquired the rights to the game when it absorbed Parker Brothers in 1991, and Ouija board commercials aimed at children have since disappeared from airwaves. Today, even though the Spiritualist movement that spawned the board has faded from public consciousness, the game's connection to the era is still part of its appeal—even if users aren't fully aware of it.

"It really is the one and only object from the age of Spiritualism that's still part of American life," Horowitz says. "Ask most people 'Have you attended a seance?' and you'll get looked at funny, but if you ask them 'Have played with the Ouija board?' and most people will say, 'Oh yes, I had a scary experience,' or 'My kid had a scary experience with something of that nature.' It's not too far off from asking someone if they've been to a seance—it just happens to be product-based."

The game has also proven harder to modernize than other classic board games; it's a tactile experience, Horowitz points out, which makes it tricky to digitize. But that doesn't mean Hasbro hasn't tried to bring the game into the 21st century: Past attempts included a Ouija board that glowed in the dark and a pink board that fit every stereotype about what young girls like—the same one that drew ire from religious groups.

But none of these reinventions have successfully replaced the classic Ouija board most people are familiar with. If you look up Ouija on Hasbro's website today, you'll find a game that resembles the same weathered, wooden tables mediums used to create their first talking boards in the 19th century—a design that may be enough to make users forget they're playing with a copyrighted board game meant for kids, and not an occult artifact.

This story has been updated for 2020.