In the 19th century, cities were grimy places, where thousands of people lived in overcrowded tenement buildings and walked streets polluted with trash, sewage, and the carcasses of dead animals. Unsurprisingly, these cities were also hotbeds of infectious disease.

One of the leading causes of death was tuberculosis, which spreads from person to person in the tiny droplets that spray through the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes. "In the 19th century, tuberculosis [was] the greatest single cause of death among New Yorkers," explains Anne Garner, the curator of rare books and manuscripts at the New York Academy of Medicine Library and the co-curator of the Museum of the City of New York’s new exhibition, "Germ City: Microbes and the Metropolis."

In the 19th century, tuberculosis killed one in every seven people in Europe and the U.S., and it was particularly deadly for city dwellers. Between 1810 and 1815, the disease—then commonly known as consumption, or the white plague—was to blame for more than a quarter of the recorded deaths in New York City. While New York wasn't alone among urban centers in having startlingly high rates of tuberculosis, its quest to eradicate the disease was pioneering: It became the first U.S. city to ban spitting.

"BEWARE THE CARELESS SPITTER"

In 1882, Robert Koch became the first to discover the cause of tuberculosis: a bacterium later named Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which he isolated from samples taken from infected animals. (Koch won the Nobel Prize in 1905 for his work.) He determined that the disease was spread through bacteria-infected sputum, the mix of phlegm and spit coughed up during a respiratory infection. That meant that rampant public spitting—often referred to as expectorating—was spreading the disease.

In 1896, in response to the growing understanding of the threat to public health, New York City became the first American metropolis to ban spitting on sidewalks, the floors in public buildings, and on public transit, giving officials the ability to slap wayward spitters with a fine or a jail sentence. Over the next 15 years, almost 150 other U.S. cities followed suit and banned public spitting [PDF].

The New York City health department and private groups like the National Tuberculosis Association, the Women’s Health Protective Association, and the Brooklyn Anti-Tuberculosis Committee generated anti-spitting slogans such as "Spitting Is Dangerous, Indecent, and Against the Law," "Beware the Careless Spitter," and "No Spit, No Consumption." They made posters decrying spitting (among other unhealthy habits) and reminding people of the ban. Members of the public were encouraged to confront defiant spitters, or, at the very least, give them the stink eye. While there were many other factors to blame for the spread of tuberculosis—like dangerously overcrowded, poorly ventilated tenement housing and widespread malnutrition—public spitters became the literal poster children of infection.

New York City officials followed through on the threat of punitive action for errant spitters. More than 2500 people were arrested under the statute between 1896 and 1910, though most only received a small fine—on average, less than $1 (in 1896, that was the equivalent of about $30 today). Few other cities were as committed to enforcing their sputum-related laws as New York was. In 1910, the National Tuberculosis Association reported that less than half of cities with anti-spitting regulations on the books had actually made any arrests.

Despite the law, the problem remained intractable in New York. Spitting in streetcars posed a particularly widespread, and disgusting, issue: Men would spit straight onto the floor of the enclosed car, where pools of phlegm would gather. Women wearing long dresses were at risk of picking up sputum on their hemlines wherever they went. And the law didn’t seem to stop most spitters. As one disgusted streetcar rider wrote in a letter to the editor of The New York Times in 1903, “That the law is ignored is evident to every passenger upon these public conveyances: that it is maliciously violated would not in some cases be too strong an assertion.”

The situation wasn’t much better two decades later, either. “Expectorating on the sidewalks and in public places is probably the greatest menace to health with which we have to contend,” New York City Mayor John Francis Hylan said in a 1920 appeal for citizens to help clean up the city streets.

THE BLUE HENRY

Spitting laws weren't the only way that health authorities tried to rein in the spread of TB at the turn of the century. Anti-tuberculosis campaigns of the time also featured their own accessory: the sputum bottle.

Faced with the fact that sick people would cough up sputum no matter what a poster in a streetcar told them, in the late 19th century, doctors and health authorities all over the world began instructing people with tuberculosis to spit into pocket-sized containers, then carry it around with them. “A person with tuberculosis must never spit on the floor or sidewalk or in street cars, but always into a cuspidor or into a paper cup, which he should have with him at all time, and which can be burned,” advised the New York City Department of Health’s 1908 publication Do Not Spit: Tuberculosis (Consumption) Catechism and Primer for School Children. These containers were known as cuspidors, spittoons, or simply sputum cups or sputum bottles.

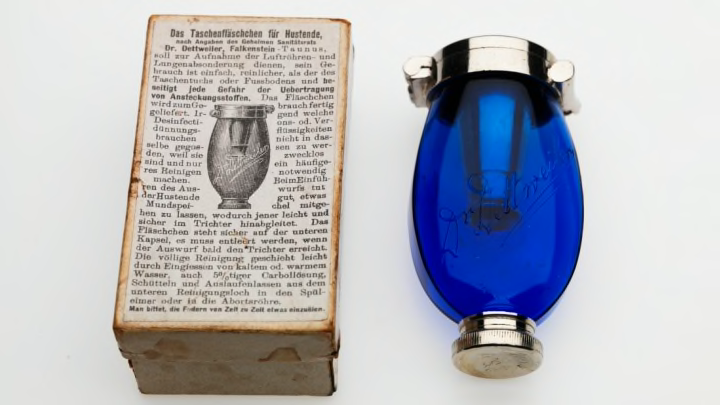

Among the most well-known of these sputum-carrying receptacles was the “Blue Henry,” a pocket flask made of cobalt-blue glass that was originally manufactured by the German sanatorium pioneer Peter Dettweiler, who himself had suffered from tuberculosis.

“The sputum bottle was like a portable flask that could be used to collect this sticky phlegm that was produced by the irritated lungs of a person suffering from tuberculosis,” Garner says. While they came in various shapes, sizes, and materials, the fancier versions would have a spring-loaded lid and could be opened from both sides, so that you could spit into a funnel-like opening on one side and then unscrew the bottle to clean out the sputum receptacle later.

Dettweiler's device and the similar devices that followed became popular all over the world as doctors and governments sought to contain the spread of tuberculosis. These receptacles became a fixture in hospitals and at sanatoriums where tuberculosis patients went to recuperate, and were a common hand-out from anti-tuberculosis charities that worked with TB-afflicted patients.

In the early 1900s, the New York Charity Organization Society was one of them. Its Committee for the Prevention of Tuberculosis raised money to buy its New York City-based clients better food, new beds, and of course, sputum cups. (Likely the paper kind, rather than the glass Dettweiler flasks.) The generosity wasn't unconditional, though. The society would potentially pull its aid if charity workers showed up for a surprise home inspection to find unsanitary conditions, like overflowing sputum cups that were not being properly disinfected [PDF].

Eventually, the city itself began handing out sputum cups. In an effort to reduce the contagion, by 1916 a large number of cities—such as Los Angeles, Seattle, and Boston—dedicated part of their municipal budgets to paying for tuberculosis supplies like paper sputum cups that would be handed out to the public for free.

Though paper sputum cups could be burned, glass or metal flasks had to be cleaned regularly. Doctors recommended that the sputum bottles contain a strong disinfectant that could kill off the tuberculosis bacilli, and that the receptacles be cleaned and disinfected every morning and evening by rinsing them with a lye solution and boiling them in water. As for the sputum itself, burning was the preferred method of sanitizing anything contaminated with TB at the time, and sputum was no exception—although rural consumptives were encouraged to bury it in the garden if burning wasn’t practical.

In an era where infectious disease was often associated with poor, immigrant communities, sputum bottles made it possible to go out in public without drawing the same attention to your condition that hacking up phlegm into the street would. “You could discreetly carry them around and then take them out and people wouldn’t necessarily know that you were suffering from the disease,” Garner explains. Or at least, somewhat discretely, since they soon became widely associated with consumptives. A Dr. Greeley, for one, argued that ordinary sputum bottles were “so conspicuous as to be objectionable," and suggested people spit into toilet paper and put that in a pouch instead. That idea didn't quite take off.

And while hiding your infectious status is not good for public health, the sputum flasks did lower the risk that you were infecting the people around you as you coughed and sneezed. “As long as you were doing it into the bottle, you probably were not infecting other people,” Garner says.

Not many of these sputum bottles have survived, in part because it was standard practice to burn everything in a tuberculosis patient’s room after they died to prevent germs from spreading. Those that remain are now collector's items, held in the archives of institutes like Australia's Museums Victoria; the Museum of Health Care in Kingston, Canada; and the New York Academy of Medicine Library.

TUBERCULOSIS TODAY

Unfortunately, neither anti-spitting propaganda nor sputum flasks managed to stop the spread of tuberculosis. Real relief from the disease didn’t come until 1943, when biochemist Selman Waksman discovered that streptomycin, isolated from a microbe found in soil, could be an effective antibiotic for tuberculosis. (He won the Nobel Prize for it, 47 years after Koch won his.)

And while carrying a cute flask to spit your disease-ridden phlegm into sounds quaint now, tuberculosis isn’t a relic of the past. Even with medical advances, it has never been eradicated. It remains one of the most devastating infectious agents in the world, and kills more than a million people worldwide every year—the exact number is debated, but could be as high as 1.8 million. And, like many infectious diseases, it is evolving to become antibiotic resistant.

Sputum flasks could come back into fashion yet.