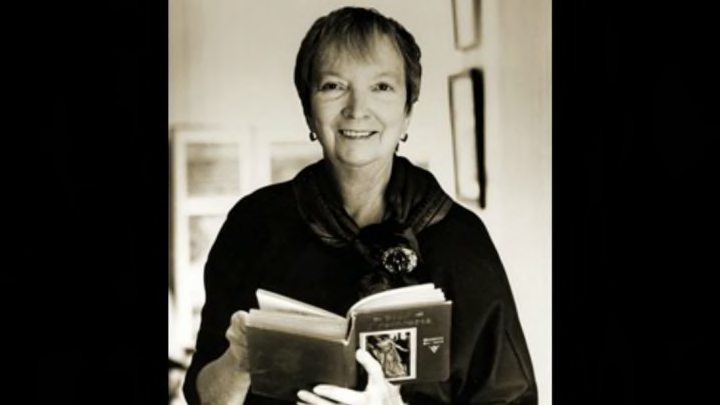

Madeleine L'Engle was a novelist, an essayist, and a poet, but she will always be best remembered for A Wrinkle in Time, in which she folded reality so that we could cross vast distances in a pinch.

As a stellar creator of families born from both her own experiences and her broad imagination, L'Engle gave us The Austins, The Murrys, and The O’Keefes. But, through her writing, she also made us members of those families. Maybe it happened when we were kids, or maybe we came to her books when we were older. But her particular skill was in conjuring responses to her adventures from readers of all ages.

On what would have been her 100th birthday, here are 10 facts about Madeleine L'Engle—a woman who will forever be in the pantheon of YA royalty.

1. She started writing at a very young age.

Madeleine L'Engle was the only child of a pianist mother and a writer father who embraced creativity. They gave her the space to read, write, play music, draw, and otherwise inhabit an internal dream world. “I’ve been a writer ever since I could hold a pencil,” she told the National Endowment for the Humanities.

2. Her dedication to individualism came from her time at boarding school.

One main theme of A Wrinkle in Time and L'Engle's other works is the danger of vast conformity. Sameness is depicted as a hellish slog, and heroes often win out because of their unique characteristics. That preference for individuality sprung from her English boarding school's convention for labeling its students with numbers instead of names. It imbued her with what she described as "an intense passion to be known by a name, not a number. You take away a name, you take away a person’s reality."

3. Her faith influenced her writing.

L'Engle, who converted to Christianity in adulthood, was clear about her dedication to religious faith and its impact on her work. Her fantasy and sci-fi writings are sprinkled with Biblical references, and she published several reflections on the Bible. A Wrinkle in Time is her counterargument to stiff-minded German theologians who had no room for seeing things differently and, as she told The Washington Post, acted as her "affirmation of a universe in which I could take not of all the evil and unfairness and horror and yet believe in a loving Creator."

4. Her books were banned in many Christian bookstores.

Even though Christianity guided her art, L'Engle rejected the “Christian author" label, as she found it reductive. It was probably just as well, as some Christians were hostile toward her books, going so far as to ban them from Christian stores and petition to have them removed from school libraries. The backlash confused and angered L'Engle, but she eventually came around to rationalizing it as good publicity.

5. A Wrinkle in Time was rejected 26 times.

When L'Engle began pitching A Wrinkle In Time to publishers under the working title Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which, they were unimpressed. Editor after editor declined the opportunity to print the novel that would go on to become a powerhouse of popularity. Though she remained convinced of the book’s potential, the dozens of rejection letters fractured her confidence as a writer for the rest of her career. Still, she refused to significantly alter the book just to see it in public (one editor suggested she cut it in half!), and she was right to remain so steadfast. John C. Farrar of Farrar, Straus and Giroux agreed to publish it in 1962, and it was an instant hit.

6. She decided to quit writing at 40 ... but kept writing anyway.

L’Engle felt guilty about all the time she spent writing that didn’t amount to a paycheck. She had published three books in the 1940s—The Small Rain, Ilsa, and And Both Were Young—but a series of failures shook her so badly that she resolved to stop writing altogether when she received yet another rejection letter in 1958, on her 40th birthday. Against her own promises, she continued writing anyway. And two years later she published Meet the Austins, which kicked off the most prolific, successful era of her career.

7. She believed that In order to write for children, you had to think like a child.

In a piece for The New York Times that ran shortly after the success of A Wrinkle in Time, L'Engle wrote that to write great literature for children, authors needed to be sincere, create layered stories, trust children to understand what adults often do not [PDF], and connect on a level that once came naturally to all of us. "Our knowledge is so often incomplete and faulty that it can stand in the way of wisdom, and only by turning back to the intuitive understanding of his own childhood can the writer transmute what he has learned into art," she said.

8. She has her own crater on Mercury.

If you’re visiting the south pole of Mercury any time soon, be sure to stop at the L’Engle crater. The International Astronomical Union officially named it in 2013 to honor her just after the Messenger Spacecraft finished mapping the planet’s surface.

9. She refused to save a character that her son didn't want to see die.

Some writers see themselves as the all-powerful architect of a story while others see themselves as conduits for emerging truths. L’Engle was in the latter camp. This tendency led her to keep story details and whole characters who popped up from outside her best laid plans, and forced her to kill Joshua [PDF] in The Arm of the Starfish—even though her son begged her to save him.

10. She had a perfect response when told A Wrinkle in time was "too difficult for children."

L'Engle firmly believed you had to trust children, especially because they would be more willing to go along with the kind of outlandish story elements at which adults might scoff. Even when A Wrinkle in Time found a publisher, they told her to expect low sales [PDF] because it was “too difficult for children.” Her response? “The problem wasn’t that it was too difficult for children. It was too difficult for adults."