The woman sat behind a table, tarot cards in front of her, a turban wrapped tightly around her head. In Jamaican-accented patois, she invited viewers to benefit from her gift of second sight. “Call me now,” Miss Cleo said, and she would reveal all.

Mostly, respondents wanted to know if a lover was cheating on them, though there was no limit to Miss Cleo's divinity. No question was too profound. She could speak with as much wisdom about concerns over financial choices as she could sibling rivalries. Her only challenge was time: Miss Cleo could connect with only a fraction of the people looking for her spiritual guidance, leaving callers in the hands of other (potentially psychically-unqualified) operators.

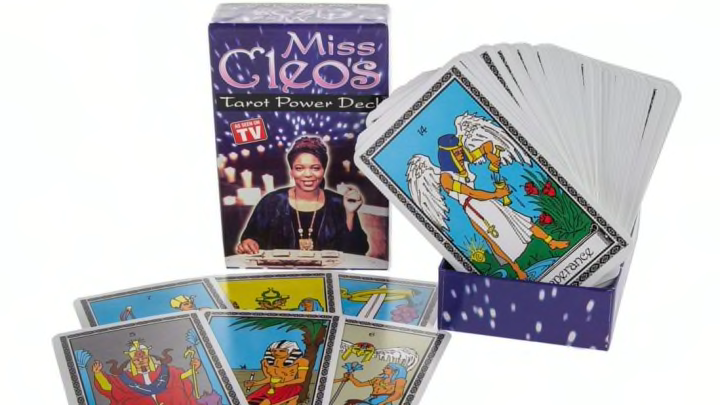

Still, Miss Cleo became synonymous with psychic phenomena, a way to consult with a medium without getting off your living room couch. From 1997 to 2002, she was a virtually inescapable presence on television—the embodiment of a carnival stereotype that annoyed native Jamaicans, who bristled at her exaggerated accent. It was nonetheless effective: Roughly 6 million calls came in to Miss Cleo over a three-year period, with $1 billion in telephone charges assessed.

Not long after, the companies behind Miss Cleo would be forced to give half of that back amidst charges that they had misled consumers. Despite being a cog in the machine, Miss Cleo herself was vilified. Of the $24 million her hotline raked in monthly, she claimed to have earned just 24 cents a minute, or approximately $15 an hour.

Most people didn’t know she was born in Los Angeles, not in Jamaica; that her real name was Youree Dell Harris; and that her late-night infomercial promising psychic assistance was little more than performance art.

Harris may have been raised in California, but Miss Cleo was born in Seattle. While living in Washington in the 1990s, Harris tried her hand at playwrighting, authoring a play titled For Women Only under the name Ree Perris, which she performed at Seattle's Langston Hughes Performing Arts Center. In it, Harris wrote and portrayed a Jamaican woman named Cleo, a clear predecessor to the character that would later pop up in television ads.

After producing three plays, Harris left Seattle amid allegations that she had taken grant money from the Langston Hughes Advisory Council, leaving some of the cast and crew unpaid. (Harris later said she left Seattle due to wanting to distance herself from a bad relationship. She told colleagues she had bone cancer and was leaving the area but that they would be paid at a later date.) She ended up in Florida, where she responded to an ad seeking telephone operators. Harris taped a commercial in character as Cleo—the hotline added the “Miss”—for $1750 and then agreed to monitor a phone line for a set wage. Operators made between 14 and 24 cents a minute, she later said, and she was on the higher end.

Psychic premonitions can be difficult to validate, though Harris never claimed to be a medium. In her own words, she was from a “family of spooky people” and was well-versed in voodoo thanks to study under a Haitian teacher. The Psychic Readers Network and Access Resource Services, a set of sister companies that used workers sourced by a third party for their hotlines, recoiled at the word voodoo and declared her a psychic instead.

If Harris was the genuine article, many of her peers were not. As subcontractors who were not employed by the Psychic Readers Network or Access directly, some responded to ads for “phone actors” and claimed they were given a script from which to work. (Access later denied that operators used a script.) The objective, former "psychics" alleged, was to keep callers on the line for at least 15 minutes. Some customers, who were paying $4.99 a minute for their psychic readings, received phone bills of $300 or more.

When the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) began responding to complaints in 2002, it was not because Harris was portraying a character or because she may have not been demonstrably psychic. It was because the Psychic Readers Network and Access were accused of deceptive advertising. Miss Cleo would urge viewers to call a toll-free 800 number, where operators would then refer them to a paid 900 line to reach a psychic. Miss Cleo also pledged that the first three minutes were free. That was true, though those first three minutes were largely spent on hold.

When people began to dispute their phone charges, Psychic Readers Network and Access were alleged to have referred accounts to collection agencies. Even if a telephone carrier like AT&T canceled the charges, customers would still find themselves subject to harassment over unpaid debt.

Individual states like Missouri and Florida sued or fined the companies, but it was the FTC that created the largest storm cloud. Of the $1 billion earned through the hotline, $500 million remained uncollected from stubborn or delinquent consumers. In a complaint and subsequent settlement, the FTC ordered those debts canceled and imposed a $5 million fine on the companies. Psychic Readers Network and Access did not admit to any wrongdoing.

As for Miss Cleo: Harris was only briefly named in the Florida lawsuit before she was dropped from it; the FTC acknowledged that spokespersons couldn’t be held liable for violations. But the association was enough, and newspaper reporters couldn’t resist the low-hanging fruit. Most headlines were a variation of, “Bet Miss Cleo didn’t see this one coming.”

Outed as a faux-Jamaican and with her Seattle past further damaging her reputation, Harris faded from the airwaves. Her fame, however, was persistent. She recorded a voice for a Grand Theft Auto: Vice City game for a character that strongly resembled her onscreen psychic. Private psychic sessions were also in demand, with Harris charging anywhere from $75 to $250 per person. Her Haitian-inspired powers of deduction, she said, were genuine.

Eventually, enough time passed for Miss Cleo to become a source of nostalgia. In 2014, General Mills hired her to endorse French Toast Crunch, a popular cereal from the 1990s that was returning to shelves. Following both the Grand Theft Auto and General Mills deals, Psychic Readers Network cried foul, initiating litigation claiming that the Miss Cleo character was their intellectual property and that Harris's use was a trademark and copyright violation. General Mills immediately pulled the ads. (The argument against Rockstar Games, which produced Grand Theft Auto, was late in coming: Psychic Readers Network brought the case in 2017, 15 years after the game’s original release. The lawsuit is ongoing.)

Unfortunately, Harris’s continued use of the image would shortly become irrelevant. She died in 2016 at age 53 following a bout with cancer. Obituaries identified her as “Miss Cleo” and related her longtime frustration at being associated with the FTC lawsuit. “According to some articles, I’m still in jail,” she told Vice in 2014. Instead, she was where she had always been: Behind a table, listening, and revealing all.