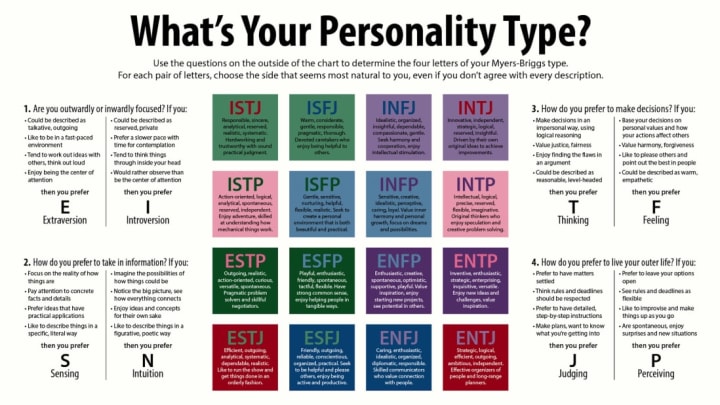

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, or MBTI, is a popular personality test that claims to differentiate 16 distinct personality types, distinguishing the extroverts from the introverts, the sensing from the intuitive, the thinkers from the feelers, and the judgers from the perceivers. Though widely criticized by professional psychologists as pseudoscience, the MBTI is still beloved by HR departments and career counselors around the globe. Here’s some background.

1. The test was the brainchild of a mother-daughter team.

Katharine Cook (married name Briggs) was born in 1875 and went to college at the age of 14, where she studied agriculture and graduated first in her class. While Briggs was expected to live as a traditional homemaker after receiving her diploma, her desire to learn remained unquenchable. She'd pour much of her energy into educating her daughter, Isabel—who, as an adult, would later help her develop the famous test.

2. For Katharine Cook Briggs, childrearing sparked a passion for psychology.

Briggs was fascinated with the “correct” way to raise a child. She began studying developmental psychology, largely kept her daughter out of traditional school, and kept a detailed diary of Isabel's developmental progress. (Briggs referred to her living room a “cosmic laboratory of baby training.”) In the meantime, she wrote about child psychology in popular magazines like The New Republic and Ladies' Homes Journal, usually writing under the pseudonym “Elizabeth Childe.”

3. Briggs began making personality tests after meeting her future son-in-law.

When a grown-up Isabel began attending Swarthmore College, she met a law student named Clarence “Chief” Myers. They two began dating and, eventually, Isabel brought Myers home over Christmas to meet her parents. The young man perplexed Katharine—his personality was so different from everybody else in their family—and she wanted to figure out why. Briggs visited the Library of Congress and began studying the psychology of personalities.

4. Carl Jung's work had a major influence on Briggs.

Everything changed after Briggs discovered Carl Jung’s 1921 book, Psychological Types. Simplified, Jung argues that human consciousness has two perceiving "function-types" (sensation and intuition) and two judging "function-types" (thinking and feeling), which are moderated by a person’s introversion or extraversion. Briggs was so fascinated by Jung’s theories that she began calling his book "The Bible" and wrote him fan mail. In 1926, she published an article in The New Republic distilling his theories into a sort of paint-by-numbers exercise entitled, “Meet Yourself: How to Use the Personality Paint Box.”

5. Isabel’s disillusionment with temp work turned her into an apostle of her mother's work.

One summer, Isabel Briggs Myers (she married "Chief" in 1918) landed an unfulfilling job at a temp agency. She later gave it up for housework, but found homemaking just as lackluster an occupation. In a letter to her mother, Myers expressed a wish for “some highly intelligent division of labor that can be worked out, so everybody works, but not at the wrong things.” (She’d eventually find satisfaction as an author, later writing a detective novel called Murder Yet to Come, which won a $7500 magazine writing contest.) Her preoccupation with finding the right work, however, boosted Isabel's interest in her mother’s research.

6. The First Myers-Briggs test was originally focused on the WWII job market.

With the adoption of the GI Bill and a new influx of working women, World War II saw the American labor force blossom. It was a boon for career consultants, too, who were seeking standardized tests that could sort all of these new workers into their ideal jobs. According to Merve Emre, author of The Personality Brokers, a slew of tests were, “made under the watchful eyes of executives eager to keep both profits and morale high.” Myers would adapt and pitch her mother’s personality tests to a consultant named Edward N. Hay, arguing that they could help people entering the workforce find their career match. Hay loved the idea.

7. The test gained popularity as a way tool for hiring—and firing—employees.

Hay pitched the test to his biggest clients: General Electric, Standard Oil, Bell Telephone, and officials in the U.S. Army. Corporate honchos were quickly convinced that, by directing the right people to the right jobs, the test could help reduce turnover. According to Emre, Myers-Briggs encouraged employers to “reassign or fire people” according to their personality types. (At an electric company, for example, introverts could be assigned clerical work while extroverts were sent out to read meters.)

8. It’s not based on any formal psychology.

One concern with the MBTI is that nobody involved in developing it had any formal education in psychology or psychometrics (the study how to objectively measure psychological traits). Briggs, a devoted autodidact, would say, “One need not be a psychologist in order to collect and identify types any more than one needs to be a botanist to collect and identify plants.” Her critics, however, disagreed.

9. The MBTI is statistically unreliable.

The Myers-Briggs indicator suffers from “low test reliability.” That is: If you take the test more than twice, there’s a good chance you’ll be classified as a different personality type. “If you retake the test after only a five-week gap, there's around a 50 percent chance that you will fall into a different personality category compared to the first time you took the test,” the philosopher Roman Krznaric wrote for Fortune. As a scientific metric, the test is consistently unreliable.

10. Professional psychologists have described the test as a "fortune cookie."

Researchers have described the MBTI as “an act of irresponsible armchair philosophy” and a “Jungian horoscope.” Critics argue that the mother-daughter team misread Jung’s work on types. (Indeed, Jung himself said that slapping personality labels onto people was “nothing but a childish parlor game.”) In the early 1990s, a U.S. Army Research Institute commissioned study concluded, “At this time, there is not sufficient, well-designed research to justify the use of the MBTI in career counseling programs" [PDF] and the psychometric expert Robert Hogan said that, "Most personality psychologists regard the MBTI as little more than an elaborate Chinese fortune cookie." Despite the criticism, the test is still used by a majority of Fortune 100 companies—all to the tune of $20 million a year.