Just before World War I, an artist and sculptor named Anna Coleman Ladd decided to focus her skills on another method of creative expression: She wrote a novel. The Candid Adventurer, published in 1913, tells the story of a portrait painter named Jerome Leigh who is obsessed with external beauty and unable to see beyond the superficial. The other main character in the book, Mary Osborne, struggles with a sense that she’s out of touch with the problems of the less fortunate. Her privileged social status keeps her “from the touch of life, from humanity in its grossness, its evil, its suffering,” even as her daughter, Muriel, tries to draw her out of her emotional isolation.

The Candid Adventurer offered a degree of foreshadowing for Ladd's own life. In just a few years, she would voluntarily remove herself from a comfortable existence as a celebrated artist in Boston and relocate to Paris, where a queue of soldiers severely injured in battle waited for her help in alleviating their suffering. Using all of the skills she’d acquired as an artist, Ladd crafted custom masks that restored their damaged eyes, missing noses, and shattered jaws. She invited them into her studio, made them feel at home, and allowed them to walk out with a facsimile of what the war had taken from them. What plastic surgery would one day do with a scalpel, Ladd did with little more than copper, plaster, and paint. She did so not only to please the Jerome Leighs of the world, who recoiled at damaged faces, but for the soldiers themselves, who feared they might never again be accepted into society.

Ladd was born Anna Coleman Watts in Pennsylvania in 1878. Thanks to her two wealthy parents, John and Mary Watts, she enjoyed an education rich in literature and the arts, both in America and abroad. She learned sculpting at the side of masters in Rome in 1900. When she returned to the States, women of prominence commissioned private works from her.

Watts’s social position, already gilded, was elevated further when she married physician Maynard Ladd in 1905. Since Maynard was from Boston, the now-Anna Coleman Ladd relocated to his hometown and attended the Boston Museum School for three years. There, she became a local celebrity for her paintings and busts.

Ladd stayed busy with her artwork and novel writing. In 1917, an art critic named C. Lewis Hind drew her attention to an article written by a man named Francis Derwent Wood. An artist by trade, Wood had joined the Royal Army Medical Corps in his early forties. After seeing the brutally disfigured men who had been brought back from the trenches to be treated by his colleague, the London-based surgeon Harold Gillies, Wood opened the Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department in the Third London General Hospital, which soon became known informally as the "Tin Noses Shop." Wood’s intent was to pick up where the surgeon left off, creating cosmetic improvements using fabricated facial appliances that filled in the empty space destroyed by war.

Ladd was convinced her skill set could achieve similar—perhaps even better—results. Through her physician husband's connections, she was able to get an audience with the American Red Cross, which agreed to help her open a studio on the Left Bank of Paris. She arrived in France in December of 1917 and had her space ready for patients by the spring of 1918. She named it the Studio for Portrait Masks.

To understand why Ladd and Wood’s expertise was needed, it helps to contextualize the state of both warfare and medicine in the early 20th century. Combatants in World War I were firing and receiving heavy artillery from automatic weapons; grenades sent shrapnel flying in all directions. Because so many men were embedded in trenches, sticking their heads out often meant receiving direct or ancillary fire. Helmets may have guarded against lethal injuries to the brain, but helmets could also be shattered, sending pieces flying into their face. Of the 6 million men from Britain and Ireland who fought in World War I, an estimated 60,500 suffered injuries to the head or to their eyes.

With parts of their faces now missing or severely damaged, these men would be carted off the field and directed toward medical stations and major hospitals. Their potentially lethal wounds would be treated, but surgical restoration of cosmetic damage was still in a relatively primitive state. Sometimes, a patient who would require several surgeries to achieve an improved appearance could only be afforded one due to a lack of time or a shortage of staff. Gillies was a smart and insightful surgeon who pioneered some of the techniques seen in modern plastic surgery, treating thousands of men at Queen's Hospital, but it was impossible to perform revolutionary procedures for every wounded patient coming through the doors.

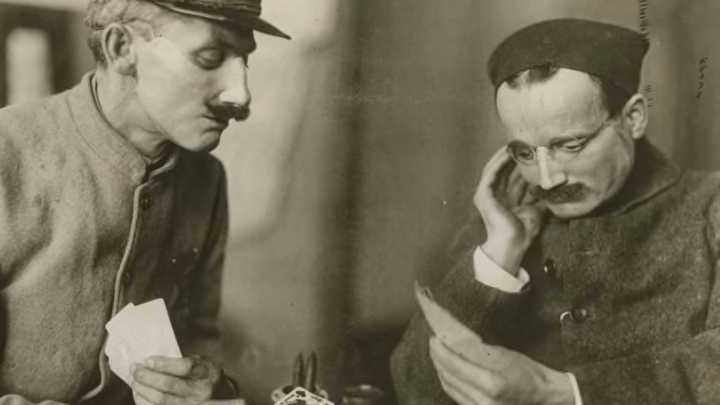

After being treated and released, the men often found great difficulty returning to their normal lives. They were self-conscious about their appearance and sometimes spoke of what they called the Medusa effect: Walking down the street, a passerby would catch sight of their collapsed cheekbones or hollow eye socket and faint. In Sidcup, England, where Gillies practiced, blue park benches near the hospital were reserved for men with disfigured faces; the color also served as a signal that the occupant of the bench might have an alarming appearance. The French referred to these men as mutilés, for mutilated, or Gueules cassées, for broken faces. Some were so despondent over their appearance they committed suicide.

It was these men Ladd sympathized with and was desperate to assist.

Ladd corresponded with Wood to gather information on how such facial injuries could be addressed through facial appliances. Though masks had been worn for centuries by people with deformities, no one had ever tried making them on such a scale before. It's been estimated that 3000 French soldiers were in need of such attention. To visit Ladd, they required a letter of recommendation from the Red Cross.

Ladd eventually settled on a process that involved making a plaster cast of the patient. First, she would invite them into the studio, which she insisted be a warm and welcoming environment. Ladd and her four assistants made the soldiers feel as comfortable as possible; she trained her staff to make jokes and not fixate on the visitors' appearances. Next, Ladd applied plaster over their faces and allowed it to dry, creating a hardened cast from which she could make a copy of the face and craft an appliance in gutta-percha, a rubber-like substance, which was then electroplated in copper. Depending on the work required, Ladd would also sometimes use a silver mesh plate covered in plaster. The missing or disfigured features were designed using reference photographs of her subject from before the war. The copper was just 1/32 of an inch thick and weighed between four and nine ounces. The mask might encompass anything from a missing nose to an entirely destroyed portion of the face, depending on the extent of damage.

Next came the step requiring Ladd’s skills as a painter. She used an oil-based enamel resistant to water and attempted to match her recipient’s skin tone somewhere between how it would look under clouds or dim light and how it might look on a sunny day. (Leaning toward either extreme would only lessen the illusion.) If a mustache was required, she crafted one out of foil. Human hairs were used for eyebrows and eyelashes. The mask was typically attached to a pair of spectacles hooked over the ears to hold it in place, or a strip hooked behind the ear.

The Red Cross produced a film (above) illustrating the process. In 1918, Ladd explained her intentions to a very curious press: “Our work begins when the surgeon has finished,” she said. “We do not profess to heal. After the wounded man has been discharged from the hospital we begin our treatment. Of course, the chief difficulty in making these masks is to accurately match both sides of the face and restore the features so that there will be nothing of the grotesque in the appearance of the covering. A mask that did not look like the individual as he was known to his relatives would be almost as bad as the disfigurement.”

The process took roughly a month before Ladd was satisfied with the result. Though her patients were primarily French soldiers, she made a handful for Americans, who—per the wishes of the American Red Cross—got expedited treatment.

All told, Ladd spent 11 months in Paris. Some estimates put her studio’s production at over 200 masks, but the figure was likely closer to 97. Considering how much time each one took Ladd and her four-person staff, it was a staggering amount of productivity, with roughly nine masks churned out every month. When the war concluded, she returned to Boston to pick up her commercial sculpting career. She was made a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor for her war service in 1932. She died in 1939 in California at the age of 60, just three years after retiring.

In the years following the war, Ladd gave lectures and spoke freely about her experiences fabricating these faces. She received letters from men thanking her for making them more comfortable with their appearance. No extensive study of these soldiers was ever pursued, however, and it’s difficult to say how the masks were incorporated into their day-to-day lives.

The items themselves were also not impervious to wear and wouldn't last more than a few years. Even if they did, the patient would eventually undergo a puzzling metamorphosis: They would age, but the mask would not. Eventually, the contrast between a flawless copper plate and wrinkled or pale skin would become too noticeable.

Some of Ladd’s subjects may have spent years in relative comfort. Others may have only had fleeting moments of normalcy, where favorable light and the company of close friends made them less self-conscious about what the war had taken from them. But in some measure, Anna Coleman Ladd had used her artistic ability to give them a respite from the misfortune that accompanied their bravery. Of those who were photographed wearing her masks, many were smiling.