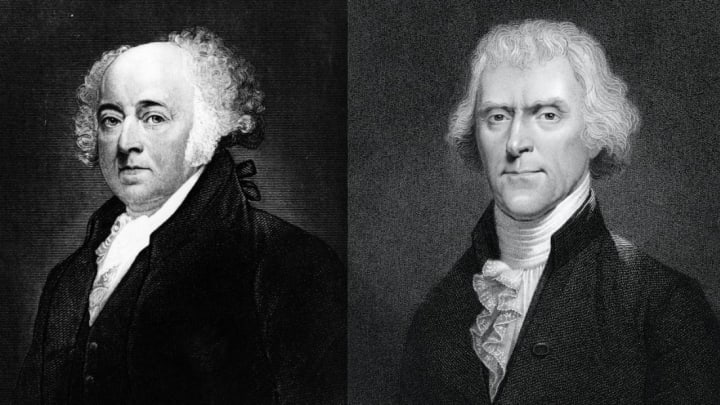

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were not impressed when they visited Stratford-Upon-Avon in 1786. Adams, who was serving as the United States’s British Ambassador at the time, called William Shakespeare’s birthplace “small and mean,” while Minister to France Jefferson complained about the entrance fee. What was meant to be a highlight of the tour—a chair that was said to be the writer’s—also failed to live up to expectations. Positioned in the corner of a room where Shakespeare used to write beside the fire, the seat was in such a sorry state that anyone who got too close risked a splinter.

Perhaps thinking they deserved a consolation prize for the underwhelming experience, the future presidents decided they weren’t going away empty-handed. Before leaving Shakespeare’s writing room, they cut off a sliver of wood from his chair to take home as a souvenir. Adams wrote afterwards: “They shew Us an old Wooden Chair in the Chimney Corner, where He sat. We cut off a Chip according to the Custom.”

Stealing an artifact from a historic site is rarely a good look for politicians, but in this case, Jefferson and Adams were just keeping with tradition.

The Tourist Scavenging Tradition

“Tourist scavenging” was a widely accepted practice among 18th and 19th-century Britons. Instead of picking up a keychain from a gift shop to remember their experience as we do today, visitors to significant places would break off pocket-sized keepsakes from actual artifacts they were there to see. It didn’t matter how old, rare, or priceless the attraction was. People traveling to Stonehenge often arrived with hammers in hand, ready to claim a chip of ancient stone for themselves—and if they forgot theirs at home, they could always rent tools from the nearby town of Amesbury when they arrived.

Many English folk brought this custom with them on their travels around the world. One English tourist in Egypt wrote his mother in 1861 to report that he had seen the Sphinx and broken “a bit of its neck to take home with us, as everyone else does.” In Literature of Travel and Exploration: An Encyclopedia, Jennifer Speake describes pilfering stones from Greek ruins as “wishing to combine adventurous travel in romantic locations with a little archaeologizing.”

This destructive method of collecting souvenirs had gotten so out of hand that by 1830 it had been given an unfortunate nickname: the English disease. British painter Benjamin Robert Haydon wrote in a diary entry coining the term: “On every English chimney piece, you will see a bit of the real Pyramids, a bit of Stonehenge! a bit of the first cinder of the first fire Eve ever made, a bit of the very fig leaf which Adam fist gave her. You can’t admit the English into your gardens but they will strip your trees, cut their names on your statues, eat your fruit, & stuff their pockets with bits for their musaeums.”

A Souvenir from Shakespeare's Chair

The chair displayed in Shakespeare's childhood home was one of the worst victims of the trend. (Though whether it was actually Shakespeare's chair, or even a replica of the chair, is unclear—but merely the fact that it was said to be is all that would have mattered to souvenir hunters.) In 1769, the year that was thought to be the 200th anniversary of the writer’s birth, Stratford-Upon-Avon exploded into one of England’s biggest tourist attractions. To mark the Jubilee, several Shakespearean relics were installed at the site, including gloves that belonged to the Bard and items carved from a Mulberry tree he allegedly planted. The chair in Shakespeare’s writing room was a favorite with visitors, and it wasn’t long before they expressed their admiration through vandalism.

Instead of cracking down on this behavior, the proprietor of Shakespeare’s birthplace found a way to profit from it. He began selling fragments of the chair for a shilling a piece. Guests looking for a little something extra could opt to buy bigger pieces. In 1785, Royal Navy officer Admiral John Byng took home a hunk “the size of a tobacco-stopper” as well as the chair’s entire lower crossbar.

By the time John Adams and Thomas Jefferson made their pilgrimage to Stratford-Upon-Avon, the piece of furniture was a dilapidated skeleton of its former self. But even if the chair didn’t look as impressive as the day it debuted, the two men couldn’t resist taking a slice—if only because everyone else was doing it at the time.

Jefferson's Piece of the Chair

Shakespeare’s chair is no longer at his birthplace, but the wood chip Adams and Jefferson collected from it is still around. It went on display at Monticello in 2006 with a tongue-in-cheek note from Jefferson reading: “A chip cut from an armed chair in the chimney corner in Shakespeare’s house at Stratford on Avon said to be the identical chair in which he usually sat. If true like the relics of the saints it must miraculously reproduce itself.”

Today, tighter security around artifacts of historic significance—as well as a greater overall respect for those objects and an understanding that they aren’t indestructible—means that tourist scavenging as a cultural tradition has mostly disappeared. Many sites had to endure decades of abuse to reach that point. The practice continued long enough for Thomas Jefferson to become the target of it: In the years following his death in 1826, many visitors to Monticello went home with bits of stone chiseled from his tomb.