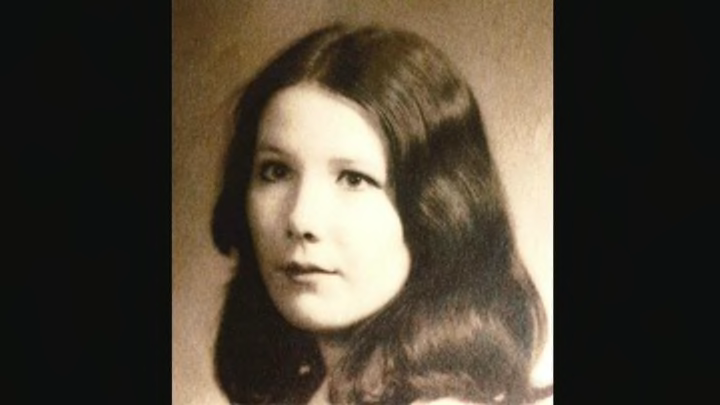

On the morning of January 7, 1969, anthropology graduate students at Harvard University gathered to take their general examinations—one last hurdle they’d have to jump before beginning their doctoral theses. One student, however, was missing: 23-year-old Jane Britton.

It wasn't like Britton to miss a test, especially one this important. Her parents, a Radcliffe College vice president and a medieval history scholar, had raised her to take her education seriously, and she had graduated magna cum laude from Radcliffe College in 1967. At Harvard, she served as a teaching assistant, helped discover the remains of a Neolithic community during an archaeological dig in Iran, and dazzled everyone with her quick wit. In short, she was more than a model student.

Her classmate and boyfriend, James Humphries, called her—but she didn’t answer. So he set off for her fourth-floor apartment at 6 University Road and knocked on her door just after noon.

Again, no answer.

Humphries’s knocking was loud enough to draw Britton’s neighbor and fellow anthropology student Donald Mitchell from his nearby apartment, and the two men decided to enter Britton’s unlocked residence.

They found her lying facedown on her bed in a blue nightgown, her body partially obscured by blankets and a fur coat. Mitchell uncovered her head, realized she was caked in blood, and promptly called the Cambridge police, who, upon arrival, asked medical examiner Dr. Arthur McGovern to come to Britton’s apartment as well.

McGovern soon confirmed the worst: Britton was dead. It was obvious that she had been the victim of a brutal murder, but there was no murder weapon in sight. With no weapon, no eyewitnesses, and the public demanding answers, detectives embarked on an arduous and baffling hunt for the truth—one that would last half a century.

The Night Of

The night before her murder, Britton and Humphries joined some classmates for dinner at the Acropolis Restaurant and ice skating at Cambridge Common. She and Humphries retired to her apartment for hot cocoa around 10:30 p.m., and, when Humphries left an hour later, Britton visited the Mitchells to retrieve her cat, Fuzzy, and enjoy a glass of sherry before returning to her own apartment at about 12:30 a.m.

Though Donald Mitchell and his wife, Jill, hadn’t seen or heard anything suspicious, two other residents had [PDF]: A neighbor heard noises on Britton’s fire escape that night, and someone else reported seeing a 6-foot-tall, 170-pound man running in the street below at 1:30 a.m. Unfortunately, neither of these testimonies gave authorities much to investigate, and they couldn’t even be certain that the murderer had in fact used the fire escape to gain access into Britton’s apartment—they saw no evidence of forced entry, and her front door had been unlocked.

As police continued their inspection of Jane's apartment, Dr. George Katsas autopsied Britton’s body at Watson Funeral Home and determined her cause of death to be “the result of multiple blunt injuries of the head with fractures of the skull and contusions and lacerations of the brain.” It was later confirmed that Britton had also been the victim of sexual assault, and a toxicology report proved that since the sherry had never entered her bloodstream, she must have died within an hour of having returned to her apartment that night.

The fact that Britton’s door was unlocked caused something of a public outcry, because it wasn’t the first time that someone had been killed in the building. Just six years earlier, Boston University student Beverly Samans had been stabbed to death in her apartment by Albert DeSalvo, better known as the Boston Strangler. After Britton’s murder, The Harvard Crimson reported that the front doors of the “littered and dingy” building didn’t even have locks, and that Britton’s apartment door was often left unlocked not out of negligence, but because it was “almost impossible to lock.” Students had allegedly complained about the lousy security in the past, though a university representative denied those claims.

A Trail of Dead Ends

Meanwhile, police were considering the possibility that someone from the university had committed the crime. They started questioning members of Harvard’s anthropology department, some of whom were Britton’s companions on the dig in Iran during the previous summer.

While canvassing the crime scene, police had found traces of red ochre—a powder-like clay—sprinkled both on Britton’s body and around her apartment. Since red ochre was once used in ancient Persian burial rites, investigators were looking for a suspect likely to have an in-depth knowledge of the subject.

It wasn’t the only reason that Jane's former companions seemed like a promising place to start: According to some media reports published in the wake of the murder, there had also been hostility among the nine participants. But, as the interrogations failed to produce any viable suspects, investigators were forced to conclude that the media reports had been exaggerated.

“There were complaints about too much tuna fish,” Professor C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky told The New York Times when asked to address the rumors. Hardly a compelling motive for cold-blooded murder. The perplexing presence of red ochre turned out to be insignificant, too—it was later determined to be nothing more than residue from Britton’s paintings.

With a bone-dry suspect pool, police focused instead on evidence from the crime scene. Though they had managed to find traces of semen left behind by the killer during the sexual assault, the existing technology wasn't advanced enough for them to use that DNA to locate a match. They also discovered that a sharp stone—perhaps sharp enough to kill— Britton had received as an archaeological souvenir from the Mitchells had gone missing from her residence.

Then, just two days after Britton’s body was found, Cambridge Chief of Police James F. Reagan announced a black-out on any further news of the investigation until he himself decided to release more information, citing inaccuracies in media coverage of the crime. He wouldn’t elaborate, but he did give one last parting update: They had located the sharp stone.

As for any other details—where they found it, for example, or if it happened to be smeared with blood—Reagan didn’t say. The public was left to assume that the potential murder weapon was yet another dead end.

Remembering Janie

In the absence of any official updates, people looked back on Britton’s life both to honor her memory and search for some clue they might have missed. She was a bright, spirited young woman who rode horses, played the piano, and decorated her apartment walls with drawings of animals.

“She could interact with a lot of different types of people very well,” Jill Mitchell told The New York Times. “She had manners, yet was very down to earth.” While Britton's varied hobbies and active social life made her a well-rounded, well-liked young woman, she was also exceptionally focused on her career goals: She specialized in Near Eastern archaeology, and planned to become an archaeologist after graduation.

Some considered the many accounts of Britton’s all-around winning personality proof that her assailant must have been a complete stranger.

“The police have a mass of material and I think it will all lead to the conclusion that no one would want to kill Janie,” her friend Ingrid Kirsch said.

Others, however, simply generated the kind of ugly gossip that so often rears its head during tragedies. One popular conspiracy theory suggested that Britton’s murder was connected to her alleged involvement in the counterculture movement of the time.

“She knew a lot of odd people in Cambridge—the hangers-on and acid heads who you would not call young wholesome Harvard and Radcliffe types,” an unnamed friend, who had known Britton in 1966, told The New York Times. “She went to a lot of their parties and was very kind to them.”

But time wore on without any news from the police department, and eventually, even the foundationless rumors petered out.

The murder of Jane Britton became another cold case. Her parents passed away—her mother, Ruth, in 1978, and her father, J. Boyd, in 2002—without knowing the truth about their daughter's tragic death.

A Belated Breakthrough

Then, in 2017, several public requests for the district attorney’s office to publicly release the case file prompted investigators to pore over the materials once again, and they decided to test the DNA sample using the latest forensic technology.

Incredibly, they found a match: Michael Sumpter, a convicted murder and rapist who had died in 2001. Without new DNA from Sumpter to verify their findings, they turned to the next closest thing—a DNA sample from his brother, whom they located through services like Ancestry.com.

The sample from Sumpter’s brother matched the original sample, ruled out 99.92 percent of the male population, and proved within reason that Michael Sumpter was in fact responsible for the rape and murder of Jane Britton.

According to the Middlesex district attorney’s office, Sumpter was no stranger to Cambridge. He lived there as a child, worked just a mile from Britton’s apartment in 1967, and was convicted of assaulting a woman in the area three years after Britton’s murder.

In November 2018, Middlesex district attorney Marian Ryan confirmed that, after nearly 50 years, Britton’s case was closed.

“A half-century of mystery and speculation has clouded the brutal crime that shattered Jane’s promising young life and our family,” Britton’s brother, Reverend Boyd Britton, said in a statement [PDF]. “The DNA evidence match may be all we ever have as a conclusion. Learning to understand and forgive remains a challenge.”