Maybe it’s Max Weinberg’s fault. In the opening seconds of Bruce Springsteen’s 1984 single “Born in the U.S.A.,” Weinberg, the drummer for Springsteen’s E Street Band, laid down some ferocious snare hits, invoking cannon blasts and fireworks and all the national pride associated with those sounds. The track explodes before Springsteen even utters a single word, casting red, white, and blue filters on a set of lyrics imbued with many more colors and layers.

Casual radio listeners in 1984 were bound to hear “Born in the U.S.A.” as an ode to patriotism, and the perfect soundtrack for President Reagan’s “Morning In America” campaign. Reagan himself invoked Springsteen’s name during an August 1984 campaign stop in New Jersey. “America’s future rests in a thousand dreams inside your hearts,” Reagan said. “It rests in the message of hope in songs so many young Americans admire: New Jersey’s own Bruce Springsteen.”

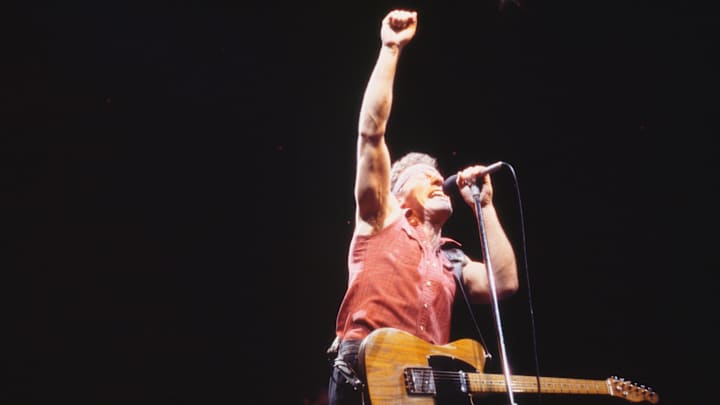

From a distance, Springsteen looked the part of the jingoistic flag-waver. The scruffy, sinewy rocker pictured on the cover of 1975’s star-making Born to Run album had evolved into a musclebound, headband-wearing, stadium-wrecking legend-in-the-making. When he sang, “I was born in the U.S.A.,” it sounded like a declaration of pride and faith.

But “Born in the U.S.A.,” the title track off Springsteen’s blockbuster seventh album, wasn'’t the nationalistic singalong many people thought it was. In his 2016 memoir Born to Run, Springsteen rightfully called it “a protest song," and the angry tone ought to be clear from the opening line: “Born down in a dead man’s town / The first kick I took was when I hit the ground.”

The song's lyrics tell of a local loser who’s railroaded into military service during the Vietnam War, scarred by his experiences in Southeast Asia, and completely forgotten about by his country when he returns home. Springsteen’s protagonist can’t find work or shake the image of the brother he lost in Khe Sanh. Ten years after the war, he’s got nothing left except a claim to his birthplace. And he’s not sure what that’s worth.

- “So they put a rifle in my hand / Sent me off to a foreign land”

- “Come back home to the refinery / Hiring man says ‘Son if it was up to me’ ”

- “I’m ten years burning down the road / Nowhere to run ain’t got nowhere to go”

“So they put a rifle in my hand / Sent me off to a foreign land”

Springsteen wrote “Born in the U.S.A.” after reading Born on the Fourth of July, Vietnam veteran and antiwar activist Ron Kovic’s memoir (which Oliver Stone later adapted into an Oscar-winning film starring Tom Cruise). Springsteen purchased the book at a gas station in Arizona in 1978 and was moved by Kovic’s story of a young man who enlists in the Marines and returns from Vietnam in a wheelchair, paralyzed from the waist down.

Not long after Springsteen read the book, he happened to meet Kovic by the pool at Hollywood’s Sunset Marquis hotel. They struck up a friendship, and Springsteen wound up staging an August 1981 benefit concert for the fledgling Vietnam Veterans of America.

In writing “Born in the U.S.A.,” Springsteen was also motivated by survivor’s guilt—or perhaps more correctly, avoider’s guilt. By his own admission, Springsteen was a “stone-cold draft dodger.” When he was called up by his local draft board in the ’60s, Springsteen used all the tricks in the book to avoid being selected. According to Rolling Stone, Springsteen’s “efforts to convince a Newark, New Jersey, selective service board of his abject unsuitability for combat in Vietnam apparently extended to claiming he was both gay and tripping on LSD, but none of it was necessary.” In the end, Springsteen was dismissed not for any of those made-up reasons, but because a concussion he had suffered in a motorcycle accident resulted in him failing his physical. He was classified 4F, or unfit for service.

“As I grew older, I sometimes wondered who went in my place,” Springsteen wrote in Born to Run. “Somebody did.” In fact, Springsteen knew some people who lost their lives in Vietnam, including Bart Haynes, the drummer in his first band. During concerts in the ’80s, Springsteen would often share the memory of Haynes coming to his house and telling him he’d enlisted, and that he was going to Vietnam, a country he couldn’t find on the map.

“Come back home to the refinery / Hiring man says ‘Son if it was up to me’ ”

Springsteen began writing what would become “Born In the U.S.A.” while compiling material for 1982’s stark acoustic album Nebraska. The original title was “Vietnam,” and an early version of the lyrics have the protagonist’s girlfriend ditching him for a rock singer. At some point in the process, Springsteen picked up a screenplay that Paul Schrader, the writer behind Taxi Driver, had sent him. It was called Born in the U.S.A., and while it was about a Cleveland bar band, not the plight of Vietnam vets, Springsteen recognized the power of the title.

Another influence was the 1979 book Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. As Brian Hiatt reveals in his 2019 book Bruce Springsteen: The Stories Behind the Songs, one draft of “Born In the U.S.A.” advocates rough justice for Nixon, suggesting we should “cut off his balls.” That line didn’t survive the editing process, but Springsteen’s anger certainly did.

There are conflicting stories about how “Born In the U.S.A.” became such a colossal-sounding song in the studio. E Street keyboardist Roy Bittan credits himself with latching onto a six-note melody Springsteen sang when sharing the song with the band for the first time. Those six notes became the central riff of the song. Having listened to Springsteen’s lyrics, Bittan aimed for a “Southeast Asian sort of synthesized, strange sound” on his Yamaha CS-80 synthesizer. It sounded even more impactful once Weinberg began slapping that snare behind it.

In Weinberg’s version of events, the floor-shaking final version of “Born In the U.S.A.” grew out of a sparser “country trio” arrangement. When Springsteen switched up and began strumming his guitar in a style reminiscent of The Rolling Stones’ "Street Fighting Man," Weinberg drummed along, and soon the whole band followed.

“I’m ten years burning down the road / Nowhere to run ain’t got nowhere to go”

Regardless of how it transpired, Springsteen was definitely down with “Born In the U.S.A.” being a rager. In the studio, engineer Toby Scott ran Weinberg’s drums through a broken reverb plate, putting a custom spin on the “gated reverb“ sound popularized by Phil Collins earlier in the ’80s. Weinberg is well-deserving of his nickname, “Mighty Max,” but technology helped to give his thunderous playing that extra oomph it needed.

The version heard on the album is an early live take, with some additional jamming removed to keep the runtime under five minutes. Springsteen has subsequently done more somber acoustic versions of “Born In the U.S.A,” but they lack the juxtapositions that make the studio version so compelling—and confusing for some listeners.

“On the album, ‘Born In the U.S.A.’ was in its most powerful presentation,” Springsteen wrote in Born to Run. “If I’d tried to undercut or change the music, I believe I would’ve had a record that would’ve been more easily understood but not as satisfying.”

“Born In the U.S.A.” ultimately is a patriotic song—just not the kind President Reagan was looking for. Springsteen’s traumatized, unemployed protagonist wants to believe that being American means something. Sex Pistols frontman Johnny Rotten once said that he didn’t write the incendiary 1977 punk single “God Save the Queen” because he hates the English—but rather because he loves them and thinks they deserve better. “Born In the U.S.A.” is the same type of song, even if some people will never understand it.

“Records are often auditory Rorschach tests,” Springsteen wrote in his memoir. “We hear what we want to hear.”

Read More About the Vietnam War in Pop Culture:

A version of this story ran in 2020; it has been updated for 2025.