At approximately 12:40 p.m. on February 13, 1960, more than 100 well-dressed college students—most of them Black—appeared at the segregated lunch counters of a trio of five-and-dime stores in downtown Nashville: Woolworth’s, McLellans, and Kress. There, they purchased menu items, took their seats, and spent the afternoon quietly reading or writing.

These coordinated activities were the first in a long series of sit-ins organized by up-and-coming leaders of the civil rights movement. Among them were Reverend James Lawson, Jr.; Fisk University student Diane Nash; and 19-year-old John Lewis, then a student at the American Baptist Theological Seminary (now American Baptist College). Following the Gandhian teachings of Martin Luther King, Jr., Lewis and his fellow activists intended these sit-ins to be completely peaceful—and for about two weeks, they were.

“Although crowds of white youths gathered in several of the stores, there was no violence,” the Tennessean reported after the third sit-in on February 20, 1960. “Many of the Negro students did their homework as they sat at the counters. Others read books or magazines. One, John Lewis, a ministerial student at American Baptist seminary, worked on a sermon.”

By that point, the number of participants in Nashville had more than tripled, and students across the country were starting to stage similar events in their own cities.

“We can’t use all the volunteers we have,” Nashville protester Luther Harris told the Tennessean at the time. “Even though we work in shifts, there just isn’t room for everybody.”

But as participation and enthusiasm for the Nashville sit-ins grew, so too did the tension with hostile segregationists who came to witness these protests for themselves.

John Lewis's Rules of Conduct

On the morning of Saturday, February 27, 1960, the protesters were gathered in Reverend Kelly Miller Smith’s First Baptist Church, preparing for that afternoon’s sit-in, when Reverend Will Campbell showed up to warn them that the police planned to let those tensions finally boil over. There would be violence, he warned, as well as arrests. But the group was undeterred.

“[W]e said we had to go,” Lewis recalled in a 1981 interview with Southern Exposure. “We were afraid, but we felt that we had to bear witness.”

For his part, Lewis was tasked with devising a code of conduct to help the protesters maintain composure and de-escalate possibly violent situations whenever possible. "Don’t strike back or curse back if abused,” “Don’t block entrances to the stores and aisles,” and “Sit straight and always face the counter” were among the tips he offered his fellow activists [PDF]. Lewis also included important reminders to “Remember the teachings of Jesus Christ, Mohandas K. Gandhi, and Martin Luther King” and “Remember love and non-violence.”

Copies of Lewis's rules were handed out to participants and fanned out to several stores downtown.

Violence Breaks Out

Just because the protestors weren't looking for trouble didn't mean those who opposed them were maintaining a similarly peaceful position. That very same afternoon's sit-ins devolved into violence when a white man struck a white protester and the Black woman beside him at Woolworth’s. It didn’t take long for other white spectators to become belligerent.

“The whites harassed the students,” the Tennessean reported, “Kicking them, spitting on them, calling them vulgar names, and putting cigarets [sic] out on their backs.”

The protestors endured the brutality with heroic stoicism, rarely straying from Lewis’s rules. Police officers looked on, but did nothing to help the victims of these vicious attacks—and eventually even began arresting some of them. While every single member of the white mob walked free, approximately 80 sit-in participants were taken to jail.

“It was the most scandalous thing that’s happened in the South since Emmett Till,” Harris told the Tennessean. “The police just pulled out and left us unprotected. Something’s got to be done. The Negro in the South has taken a lot but there is just so much he can take.”

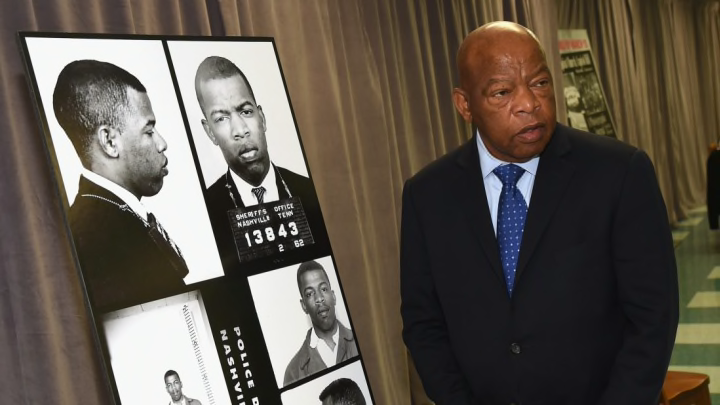

John Lewis was among those who were arrested—a first for the future Congressman, but hardly the last. Over the course of his career as a civil rights activist, Lewis was arrested more than 45 times.

“We didn't welcome arrest. We didn't want to go to jail,” Lewis said. “But it became … a moving spirit. Something just sort of came over us and consumed us. And we started singing ‘We Shall Overcome,’ and later we started singing ‘Paul and Silas bound in jail, had no money for their bail ...’ It became a religious experience that took place in jail.”

Lewis and his fellow protestors were released late that night, and Nashville Mayor Ben West agreed to meet with a coalition of Black ministers regarding the injustice of the arrests on Monday. Though West’s openness toward dialogue was a promising sign for the movement, it would be months before he actually began to dismantle segregation in the city.

A Pivotal March

The Nashville sit-ins continued into the spring. Then, after a bomb exploded on the property of NAACP civil rights attorney Z. Alexander Looby on April 19, 1960, thousands of protesters marched to City Hall. West met them on the front steps, and when Nash asked him if he recommended the desegregation of lunch counters, he said yes.

“That’s up to the store managers, of course, what they do,” West clarified. “I can’t tell a man how to run his business.”

It wasn’t exactly a definitive end to segregation at lunch counters, but West's public declaration did help get the ball rolling. In the following weeks, civil rights leaders and local business owners worked on a plan to end segregation at six lunch counters in Nashville, including Woolworth’s, McLellans, Kress, Walgreens, Harveys, and Cain-Sloan. On May 10—much like they had done at their first sit-in—Black students entered the establishments, purchased their meals, ate undisturbed, and left.

The Beginning of "Good Trouble"

Nashville was the first city to desegregate its lunch counters, and the long months of sit-ins served as a testament to the efficacy of peaceful protests. Even Martin Luther King, Jr. praised the “electrifying movement of Negro students [that] shattered the placid surface of campuses and communities across the South.”

For John Lewis, who would come to work closely with King, it was the beginning of a lifelong commitment to what he so memorably referred to as “getting in good trouble.”

“The underlying philosophy was the whole idea of redemptive suffering—suffering that in itself might help to redeem the larger society,” Lewis said of the sit-ins. “We talked in terms of our goal, our dream, being the beloved community, the open society, the society that is at peace with itself, where you forget about race and color and see people as human beings. We dealt a great deal with the question of the means and ends. If we wanted to create the beloved community, then the methods must be those of love and peace.”

On Friday, July 17, 2020, John Lewis died at the age of 80 following a six-month battle with pancreatic cancer. In addition to being a noted civil rights activist, Lewis—who was one of 10 children born to sharecroppers in rural Troy, Alabama—was a leading member of the Democratic party. After being elected to Congress in 1986, he was reelected 16 times, serving Georgia's 5th congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1987 until his death.