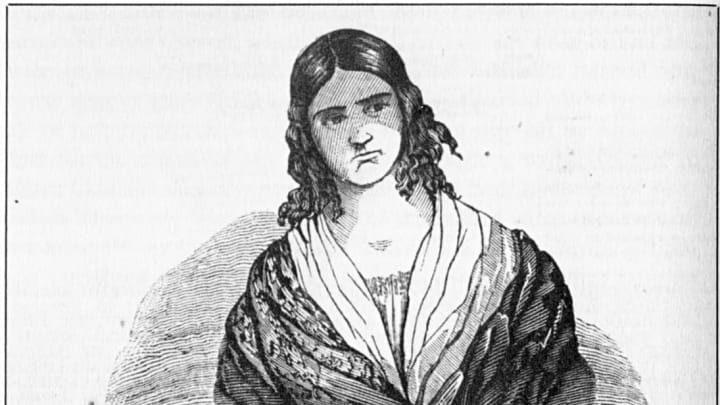

When an English immigrant named Ann Trow Sommers first arrived in New York City in 1831, she had no idea how notorious and vilified she’d soon become. In a matter of years, she’d craft a whole new identity for herself as Madame Restell, a prominent and wealthy abortionist, famous across the country. Her success only made her more hated, and she soon became a fixture in city guides for her lavish homes and Fifth Avenue lifestyle. One guide famously declared her “the wickedest woman of New York.”

Becoming Madame Restell

Sommers came to the United States with her new husband and infant daughter, intending to start a new life as a family. But within a few months, her husband died of bilious fever. Sommers had little formal education and tried to support herself as a seamstress, but the work was unsteady—so she began selling contraceptive potions.

Historians are unsure when, exactly, Sommers started this business, but in 1836, after marrying Charles Lohman, a printer for the New York Herald, she expanded her practice with his encouragement. She went from merely selling contraceptives and abortifacients to offering advice. She opened a boarding house for women to give birth anonymously and—for a fee—helped them adopt out their unwanted babies. She also facilitated surgical abortions, when requested.

But, as Adina Cheree Carlson, author of The Crimes of Womanhood and professor at Arizona State University, tells Mental Floss, “her real genius was in advertising. She was the pioneer in putting these little, discreet ads in all the newspapers.”

Sommers's first ad ran in The New York Sun on March 18, 1839. “Is it moral for parents to increase their families, regardless of consequences to themselves, or the well being of their offspring, when a simple, easy, healthy, and certain remedy is within our control,” the ad asked. “The advertiser, feeling the importance of this subject … has opened an office, where married females can obtain the desired information.”

She concocted a story that she had traveled to Europe to study midwifery and began referring to herself as “Madame Restell, female physician.” Soon, her ads became so successful that several imitators began advertising, too.

A Growing Backlash

At the time, birth control and abortion weren’t illegal in New York or the wider United States—at least not before “quickening,” which was when the mother felt the fetus move. In addition, “abortion was not considered a medical issue,” explains Linda Gordon, New York University professor and author of The Moral Property of Women, explains to Mental Floss. It was performed by midwives, and it wasn’t unusual for city abortionists to call themselves physicians, even with no formal training. (There was no accreditation for medical schools until 1912 and no standard training for doctors until around 1915.)

This didn’t stop Restell from being arrested many times—and the press loved to sensationalize each of her trials. “Restell became well-known for her medical practice because she was made scandalous and it sold newspapers,” Leslie Reagan, history professor at the Univeristy of Illinois and author of When Abortion Was a Crime, tells Mental Floss in an email. “She was wealthy and had fabulous homes, all of which drew attention to her.”

Soon, her very name became negatively synonymous with abortion—even as her business boomed. “Every time they changed the law,” Carlson says, “somebody would try to bring Restell down and there would be a trial. And they just kept at it.”

Her first arrest was in 1840, when a former patient dying of Tuberculosis confessed she had an abortion. Restell was convicted, though her case was appealed. When she was retried, an appellate court ruled the dying declaration inadmissible, and Restell was found not guilty.

In 1845, abortion became a misdemeanor before quickening, and Restell was arrested again two years later. A doctor had turned in one of her patients, who then testified against her. Restell was found guilty and served one year in jail. After leaving prison, she stopped surgical abortions and focused on pills, the boarding house, and adoptions. But she could never escape her villainous reputation.

An Obvious Target

While there are no reliable records of abortions performed in New York City at that time, there was a perception among “regular” doctors who specialized in gynecology and obstetrics that the practice was becoming pervasive. Eager to edge out midwives and “unschooled” physicians, they founded the American Medical Association in 1847. They then applied pressures on state legislatures to change laws—including contraception and abortion laws.

“Regular” doctors in the AMA argued that both contraception and abortion loosened morals and made it easier for adulterers to hide their crime. (Adoption was vilified for the same reason.) Many also showed concern for who was having abortions, Reagan tells Mental Floss. “[It was] primarily married, middle-class, white, Protestant women who were failing to do their 'duty' as women, to their families, and to the nation. If they refused to have children,” she explains, “other non-white and non-Protestant groups—namely Catholics, Black freedpeople, Chinese, and others—might gain power.”

This group of abortion-having women was also tied to the growing women’s right movement. Women were becoming more educated and were fighting for the right to participate in politics. Some were beginning to speak out about slavery and male morality issues, such as alcohol and prostitution. The movement was also campaigning for “voluntary motherhood,” Gordon says, and that “was actually really quite radical because it was calling for the right to refuse to have sex with their husbands.”

In 1873, the Comstock law passed, making it illegal to sell, give away or possess any “obscene” book, pamphlet, picture, drawing, or advertisement. It also made no distinction between contraception and abortion, prohibiting both. Anthony Comstock, who was behind the law, embarked on a campaign to find violators—and Restell was an obvious target. Comstock pretended to be a married man worried about his wife’s health after multiple children. After she sold him some contraceptive pills, he returned with the police.

“The supreme irony was that after all their years of campaigning, the medical establishment had successfully gotten New York to outlaw abortion and that law had nothing to do with her final capture,” Carlson writes in The Crimes of Womanhood. “Restell’s acts were no longer really at issue. She was targeted because of her symbolic stature.”

Restell was older then, a widow, and estranged from her daughter. She had less will to fight her arrest. On April 1, 1878, she died by suicide while out on bail. “Madame Restell was the embodiment of the great American experiment,” Carlson writes. “An immigrant, a female, an entrepreneur—she transformed working-class Ann Lohman into wealthy leisure-class Madame Restell.” But in the end, she was buried at Sleepy Hollow cemetery, and her name continued to be used as a caricature of the “evil” abortionist for decades to come.