For too long, Black women have been relegated to certain roles and even limited occupational possibilities due to the intersection of their race and gender. However, there have been plenty of exceptional women throughout history who have sought to defy the odds and pave the way for those aspiring to follow in their footsteps. Jackie Ormes is the perfect example of that kind of trailblazer.

Born Zelda Mavin Jackson in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on August 1, 1911, Ormes spent much of her time in school drawing and writing. Eventually, she went on to be a journalist and a cartoonist, becoming the first Black woman to have her own newspaper comic strip. And she didn't stop at just one—throughout her career, she created comics like Torchy Brown in "Dixie to Harlem" (1937-1938), Patty-Jo 'n' Ginger (1945-1956), and Torchy in Heartbeats (1950-1954). Here are six interesting facts about her life and career that unveil the bigger picture of her legacy as a cartoonist.

1. Jackie Ormes's first comic strip was Torchy Brown in "Dixie to Harlem."

From 1937 to 1938, Ormes wrote and illustrated Torchy Brown in "Dixie to Harlem," an ongoing comic strip featuring the eponymous Torchy's adventures as a quirky dancer and singer working her way up to the Cotton Club. The comic appeared in historically Black newspapers like The Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier, which at one point had a circulation of 358,000 households around the country. Focusing on the struggles of a country girl trying to transition to city life, Torchy Brown echoed many of the experiences of Black people during the Great Migration out of the South.

2. Her comics regularly tackled controversial issues.

Ormes didn’t just create comics with humorous and lighthearted characters—she created stories and narratives that were incredibly controversial during the Jim Crow era when Black voices, especially women's, were usually silenced. In one Patty-Jo 'n' Ginger (1945-1956) comic strip, about a young smart-alec girl and her older sister, Patty-Jo says to Ginger, "How’s about getting our rich Uncle Sam to put good public schools all over, so we can be trained fit for any college?" This was in response to the deplorable conditions of Black schools during segregation compared to the well-kept schools for white students.

The strips also tackled topics like military industrialization, environmentalism, racism, feminism, and class inequity. In one comic, Ormes even gave a pointed response to the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy who was killed for allegedly whistling at a white woman in Money, Mississippi. In the comic, made up of a single panel, a disgusted Patty-Jo approaches her sister and says, "I don’t want to seem touchy on the subject ... but, that new little white tea-kettle just whistled at me!"

3. Jackie Ormes's Patty-Jo doll broke new ground for Black toys.

In 1947, Ormes teamed up with the Terri Lee Doll Company to create a doll based on her Patty-Jo character. Much like the various looks the character had in the comics, the Patty-Jo doll was given vast wardrobe collections including fancy shoes, lavish ball gowns, and even cowgirl outfits. As The Guardian points out, this was about a decade before Barbie debuted and made that sort of thing routine.

Ormes's goal was to combat the racist Black dolls on the market that relied on mid-20th-century stereotypes like "mammies" and "picaninnies." Instead, her Patty-Jo was an upscale doll that depicted Black girls as attractive, witty, and elegant. The mandate from Ormes was simple: create a doll that Black children would be "proud to own" [PDF].

4. The FBI had a detailed file on Jackie Ormes.

During the paranoia of the McCarthy era, the government collected 287 pages of information about Ormes, filled with unwarranted concerns about her social circle and the subversive activity they might have been up to (funnily enough, none of the files touched upon her comics). The FBI monitored Ormes from 1948 to 1958, following her around and asking acquaintances—and even Ormes herself—questions about her possible communist leanings. According to the African American Intellectual Historical Society, the 287 pages in Ormes's file were 150 more than the FBI had on Jackie Robinson.

5. Jackie Ormes preferred to depict strong-minded women in her comic strips.

In 1950, Ormes revived her Torchy character in Torchy in Heartbeats, a nationally syndicated strip in full color (a first for Ormes) that was featured in 14 newspapers, including The Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier. In this strip, Torchy is a more mature, self-sufficient woman searching for authentic love. It was Ormes's chance to show off her love of fashion and depict a Black woman that’s not just an achiever, but an icon. Torchy’s boyfriend is a doctor, and together, they take on racism and other social issues.

During an interview that took place toward the end of her life, Ormes explained that "Torchy Brown could never have been some kind of mushy soap opera. She was no moonstruck crybaby, and she wouldn’t perish between heartbreaks. I have never liked dreamy little women who can’t hold their own."

6. Jackie Ormes was inducted into the Will Eisner Comics Hall of Fame in 2018.

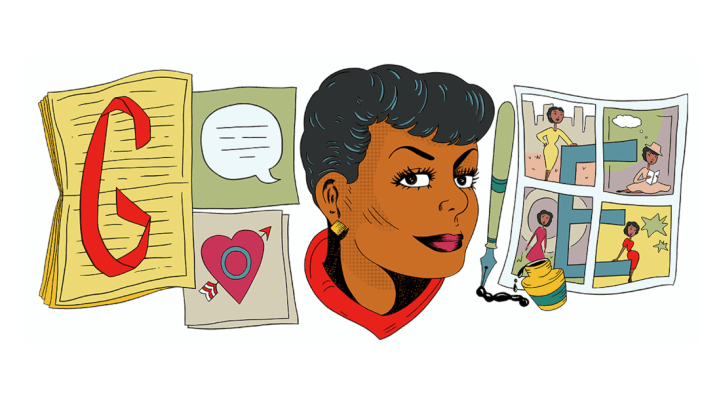

Jackie Ormes died of a cerebral hemorrhage on December 26, 1985, at the age of 74. But in recent years, her contributions to popular culture have been rediscovered. She was posthumously inducted into the Will Eisner Comics Hall of Fame in 2018, roughly 80 years after her career began. It was also announced that Ormes is set to be showcased in a yet-unreleased film project by Susan Reib, who has dedicated over two decades of her career developing material on Ormes. And on September 1, 2020, the legendary cartoonist's legacy got another mainstream boost when she became the subject of a Google Doodle by artist Liz Montague.

This article was originally published in 2021; it has been updated for 2022.