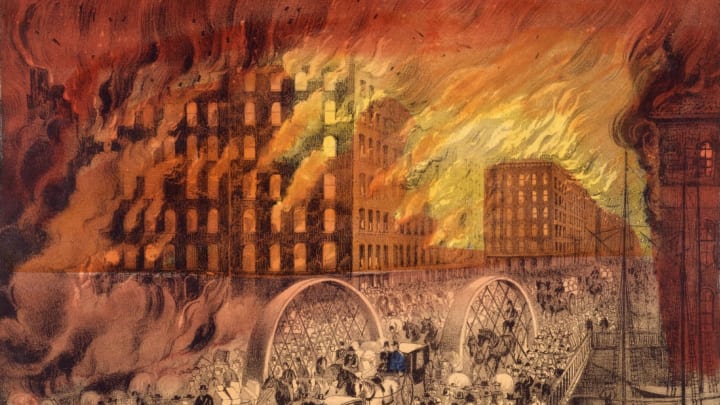

On October 8, 1871, Chicago was transformed into a hellish inferno. For two days the city burned as firefighters struggled to get control of the blaze. By the time a sudden rain helped extinguish the flames, 300 people were dead, 100,000 more were homeless, and $200 million in damage—the equivalent of nearly $4.5 billion today—had been done.

Like a phoenix, Chicago rose from the ashes. A century and a half later, the city glows like an ember along the blue shores of Lake Michigan, a testament to the resilience of the city’s people. To help you separate fact from fiction, here are some facts you may not have known about the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

1. Mrs. O’Leary did not start the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. (Neither did her cow.)

While it is widely believed that the fire began when Mrs. O’Leary’s cow knocked over a lantern, it is likely that the myth of Mrs. O’Leary’s culpability resulted from a mix of xenophobia, misogyny, anti-Catholic sentiment, and classism. Joseph Medill, who co-owned the Chicago Tribune at the time, often wrote anti-Irish screeds in the paper. Another reporter from the time, Joseph Edgar Chamberlain of the Chicago Evening Post, was blunt in his assessment that “that neighborhood” where the fire began “had always been a terra incognita to respectable Chicagoans.” The truth is no one is sure how the fire began, and Mrs. O’Leary and her cow were officially exonerated in 1997.

2. There were fire tornados.

Known as fire whirls or convection whirls, the scorching hot air—upon coming into contact with cooler air—began spinning “like a hurricane, howling like myriads of evil spirits,” according to one eyewitness. These flames could form walls of fire that reached up to 100 feet into the air, turning the city into a proverbial hell on earth.

3. The Great Chicago Fire was not the worst fire in the Midwest that month.

At the same time as Chicago burned, the Peshtigo Fire was raging in Wisconsin, directly to the north along the shores of Lake Michigan. Born of the same conditions as the Chicago fire, the Peshtigo Fire was far larger, leaving a path of destruction that was 10 miles wide and 40 miles long. It was also more deadly; approximately 1500 people lost their lives in the Peshtigo Fire.

4. The reason Chicago burned so quickly was because it was mostly made of lumber.

While we think of cities as places of concrete and steel, in the 19th century, most of Chicago’s buildings were made of timber logged in the forests of Wisconsin. Even its roads and sidewalks were built using planks, which became deadly infernos making escape difficult.

William Ogden, who served as Chicago’s first mayor from 1837 to 1838, was also largely responsible for developing the timber industry in the region at the time. According to the Peshtigo Fire Museum, Ogden “established a barge line between Peshtigo Harbor and Chicago” before developing railroad lines to better transport his lumber. Ogden, who also owned a lumber company in Peshtigo, lost the bulk of his personal possessions and most of his business holdings between the two fires.

5. The Great Fire led to the gentrification of Chicago.

It is popularly thought that the fire led Chicago to become a world leader in skyscrapers, but the truth is it took another decade for the skyscraper boom to begin. That doesn’t mean working class Chicagoans were spared the pitfalls of gentrification, though. As Jerry Larson, a professor emeritus of architecture at the University of Cincinnati told WTTW, “most of the buildings were rebuilt almost exactly as they looked before the fire.” Building with materials other than wood was cost-prohibitive, meaning working-class Chicagoans who couldn't afford more fire-resistant materials were forced out of Chicago's downtown area.

6. Not all of Chicago burned.

In the popular imagination, Chicago was left in ruins, but the truth is a little less sensational. While most of Chicago's downtown area—the city's central business district—was destroyed, much of the city’s West Side remained unscathed. Crucially, the stockyards on the South Side, most of the city’s railroads, and the wharfs, mills, and lumberyards along the Chicago River remained untouched by the flames, allowing the city and its economy to rapidly recover and continue as the “hog butcher of the world.”

7. The Great Chicago Fire offers lessons for climate change.

Few people realize just how dry Chicago was during the summer and autumn of 1871. According to WGN meteorologist Tom Skilling, “the last significant rain event before the fire was 1.57 inches on July 3,” and the period from the Fourth of July through to the day of the fire remains the driest period in Chicago's history. Given rising global temperatures and an increasing number of droughts leading to wildfires, the circumstances that led to the Great Chicago Fire may offer lessons for our changing climate.

8. An Oscar-winning film was made about the Great Chicago Fire.

More than 60 years after the fire, a film about the inferno would take Oscar gold. In Old Chicago, which was released in 1938, presents a fictionalized version of the events leading up to the blaze. The film follows the exploits of Dion O’Leary, the son of Mrs. O’Leary, played by Tyrone Power. Though the film took great historical liberties by inventing and renaming characters, it went on to earn six Academy Award nominations, with Alice Brady winning Best Supporting Actress for her portrayal as Mrs. O’Leary.