There are few things more dramatic than a huge explosion, and explosions on ships are no exception. For centuries, boats have been blowing up with amazing spectacle and horrible tragedy. Here are five ship explosions just as worthy of a three-hour dramatization as the R.M.S. Titanic.

1. H.M.S. Augusta

In October 1777, the fate of the American colonies was uncertain. New York was still under British control, and Philadelphia had just fallen into enemy hands after the Battle of Brandywine in September. But the American rebels still controlled the Delaware River—the only route for supply ships to reach Philadelphia. And the Continental Army had no intention of letting the British in.

On the evening of October 22, the British ship H.M.S. Augusta went up the Delaware River to get in position for a next-day attack of the American defenses. But the tide fell during the night, and the Continental Army woke up to an enemy ship hopelessly stuck in a sandbar. The ship caught fire during the ruthless bombardment that followed. When that fire reached its gunpowder-filled magazine, the Augusta exploded.

The noise rattled windows in Trappe, Pennsylvania, over 30 miles away. Thomas Paine, author of Common Sense, described it in a letter to Benjamin Franklin as “a peal from a hundred cannon at once.” The H.M.S. Augusta was the largest ship to be destroyed in the American Revolution.

2. U.S.S. Randolph

The British Navy ruled the seas at the time of the American Revolution. The Continental Congress understood that any navy would be miniscule by comparison, but decided that a small fleet was better than nothing. In July 1776, the U.S.S. Randolph joined a fleet of 13 frigates that made up the original American Navy.

The Randolph set out on its maiden voyage in February 1777, during which its mainmast fell into the sea. After substantial repairs (which were twice held up by lightning strikes to the mast) the ship sailed down to Florida in search of British merchant ships.

On the afternoon of March 7, 1778, the Randolph was sailing off the coast of Barbados with four other American ships when its crew spotted a lone British ship on the horizon. The convoy finally got close enough in the early evening to raise the American flag and fire their cannons. Unfortunately, their target ship turned out to be H.M.S. Yarmouth, a huge 64-gun British naval vessel. When the Yarmouth returned fire, the Randolph’s powder magazine exploded.

Huge chunks of flaming wreckage from the Randolph rained down on the Yarmouth’s deck, killing five sailors and wounding 12. The other American ships promptly scattered. The British warship attempted to pursue the other vessels, but its sails were badly damaged and the American ships successfully reached safe harbor. On March 12, the Yarmouth picked up four sailors floating on a makeshift raft, the only survivors of the Randolph’s 315-person crew.

3. Pulaski

In the 1830s, steam-powered trains were just beginning to crisscross the northeast. In the south, steam-powered boats continued to be the most efficient transportation. The steamship Pulaski traveled between Savannah, Georgia, and Baltimore, Maryland, with a stop in Charleston, South Carolina. Its passengers used the service to travel to northern vacation homes, attend horse races in Saratoga Springs, or conduct business in different cities.

On June 14, 1838, the Pulaski left Charleston for its overnight voyage to Baltimore. At 11:04 p.m., the starboard boiler exploded, ripping the ship in half. Some passengers were killed immediately by the explosion or scalding steam. Others were thrown into the water. The ship had only four lifeboats for the nearly 200 people onboard—and to make matters worse, only two of those were capable of floating. Some passengers clung to the wreckage and bits of furniture as they waited to be rescued. Only 59 people survived.

The Pulaski is sometimes called “the Titanic of the South” due to the similarly catastrophic conditions and the loss of wealthy passengers. In 2018, the wreck of the steamship was discovered off the coast of North Carolina.

4. Pennsylvania

From 1850–1900, the Mississippi River was crowded with commerce from “the Golden Age of Steamboats.” During this time, a boy named Samuel Clemens dreamed of becoming a steamboat pilot. He achieved his goal in 1857, and would later adopt the nautical term for 12 foot water as his pen name—Mark Twain.

Clemens served as a cub pilot on the steamboat Pennsylvania from September 27, 1857 to June 5, 1858. He arranged for his younger brother Henry to work as a mud clerk (a 19th-century version of an unpaid intern) and came to his brother’s defense when the pilot, William Brown, began harassing him. Clemens was fired for leaving his post, but Henry stayed onboard.

At about 6 a.m. on June 13, the engineer in charge of monitoring boiler pressure walked away from his post to speak with some women passengers. Soon afterward, four boilers exploded. Henry’s berth was above the boiler room. Although he survived the initial blast, his skin and lungs were badly burned, and he died of his injuries in a Memphis hospital eight days later. Clemens, who felt responsible for his brother’s death, had dreamt that his brother would die mere days before the accident; that dream continued to haunt his sleep for the rest of his life.

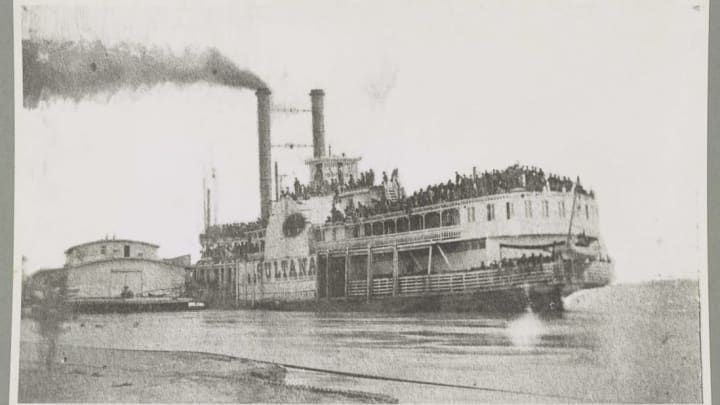

5. Sultana

After the American Civil War ended on April 9, 1865, tens of thousands of prisoners of war wanted to go home. Thousands of captured Union soldiers were brought to a small parole camp in Vicksburg, Mississippi, to await transport.

The Sultana’s Captain, J. Cass Mason, heard the government was offering to pay $5 for the transportation of an enlisted man and $10 for every officer. He promptly decided to take as many men that could physically fit onto his ship. The Sultana’s legal capacity was 376 passengers; when it left Vicksburg, it had over 2000.

Before leaving port, a local boiler-maker declared one of the boilers was faulty, and at Captain Mason’s insistence, he put a patch over the problem area. The captain decided a replacement could wait until after the steamer reached St. Louis. But the engine wouldn’t last that long. At around 2 a.m. on April 27, one of the boilers exploded.

A burst of steam erupted at a 45-degree angle, blasting through the crowded decks and destroying the pilothouse. Soldiers from Tennessee and Kentucky, who had been crowded around the boiler room, died instantly. Shrapnel from the first explosion penetrated the other boilers and set off more blasts. More men died as the ship’s smokestacks collapsed and the wood caught fire, forcing the desperate prisoners to jump into the water. A lot of them couldn’t swim, or were too weak from their imprisonment to try.

Roughly 760 survivors were brought to a hospital in Memphis, many of them rescued by local Confederates. The Sultana’s death toll is estimated at about 1200, making it the deadliest maritime disaster in American History.