Most of us spend our days walking around with our eyes pointed straight ahead or looking around, seeing the rest of the world mostly at eye-level. But there are advantages to looking down, and not just because it helps you avoid stepping on other people’s feet. Strange, wondrous, and occasionally terrible things have been found stuck to the surface of city streets—just take a look at the examples below.

1. Toynbee Tiles

If you have a revolutionary idea to share with the masses, you could write an op-ed in a major paper, talk to a local member of congress, start an activist organization, or pay for a PR campaign. Or, you could carve the message into a square of gummy linoleum and stick it in the street. Whatever floats your boat!

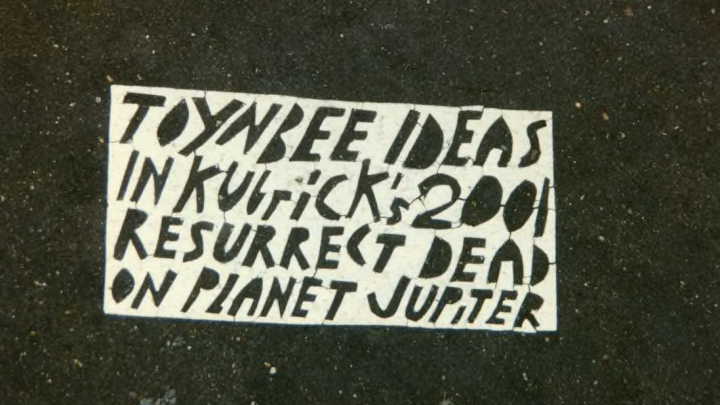

The linoleum method is the one employed by the mysterious creator of the Toynbee Tiles—lettered rectangular plaques that have appeared in dozens of major U.S. cities since the 1980s, as well as in several South American locations. Most of the tiles contain some version of the following message:

TOYNBEE IDEA

IN KUBRICK'S 2001

RESURRECT DEAD

ON PLANET JUPITER

Tile-followers, and there are a few, generally interpret Toynbee as a reference to 20th century British historian Arnold J. Toynbee, although some think it could refer to the Ray Bradbury short story "The Toynbee Convector." The 2001 is, of course, a reference to Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, which depicts a voyage to Jupiter.

No one knows who's behind the tiles, and it may not be a single individual. For years, many tile enthusiasts believed they were the work of James Morasco, a Philadelphia carpenter who communicated with the Philadelphia Inquirer in the early 1980s about the idea of resurrecting the dead on the planet Jupiter. But the tiles have continued to appear long after Morasco's death in 2003, and his widow claims he never had anything to do with them.

The story gets much, much weirder. David Mamet claims the idea for the tiles came from one of his plays; many of the tiles contain screeds against the mafia, media, and the Jews; Larry King is somehow involved. For those who are intrigued, the excellent 2011 documentary Resurrect Dead delves deeper into the mystery.

2. The Paris Central Guillotine

It’s been called “the most awful spot in Paris.” These five rectangular indents near the Pére-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris look ordinary enough, but they have a grisly tale to tell. They’re actually slabs that once formed the foundation for the Paris guillotine, which sliced off 69 heads—in public—between 1851 and 1899. (France continued sending people to the guillotine until 1977, but not here.) The guillotine stood at the entrance to the now-demolished Prison de la Roquette, and shut down when the prison itself ended its dark days.

3. The Hess Triangle

It may be the ultimate New York-style "screw you, buddy," at least as far as the city's streets are concerned. Where 7th Avenue and Christopher Street cross in Manhattan's West Village, there's a mosaic triangle that takes up about 500 square inches. Its black letters spell out an oddly aggressive message: "Property of the Hess Estate which has never been dedicated for public purposes."

The message, and the triangle, are a remnant of a very minor early 20th century property battle, in which New York City used eminent domain to seize a nearby apartment building when expanding the IRT subway in the late 1910s. The apartment building was owned by Philadelphia landlord David Hess, whose family later noticed that the city’s seizing had left them this one tiny triangle. City authorities asked the family to donate the triangle, but they refused, installing this defiant mosaic instead, in 1922. It’s a little outdated, however: in 1938, the family finally gave up and sold the plot to the owners of Village Cigars for $1000, or $2 per square inch.

4. Jewish Tombstones

During World War II and for decades afterwards, Jewish tombstones in Poland were treated as construction material, plundered from cemeteries to pave streets, courtyards, and passageways, and used to repair walls and curbs. In 2014, the city of Warsaw agreed to return 1000 Jewish tombstones, known as matzevot, that had been used to build a pergola and stairs inside a city park.

Polish photographer Łukasz Baksik spent several years documenting the tombstones’ appropriation as paving material and masonry, with the results published in a book called Matzevot for Everyday Use. Meanwhile, a nonprofit called From the Depths runs the Matzeva Project, which aims to find and restore some of the millions of gravestones still hidden in Poland, as well as the often-forgotten Jewish cemeteries from which the stones were stolen.

5. Potholes Crying out for Help

Potholes are the mosquito of urban infrastructure problems: minor but persistently irritating. Over the past few years, several people have been trying new approaches to getting them repaired. In Panama City, the TV show Telemetro Reporta launched a project in 2015 installing motion-sensitive detectors in the city’s potholes. When a car ran over the sensor, the device automatically sent a tweet to the Ministry of Public Works. In Chicago, artist Jim Bachor took a more delicious approach, creating mosaics of popsicles and other items inside potholes both in Chicago and Jyväskylä, Finland. The crudest—but potentially most effective—technique comes from Manchester, where a man who identified himself to the BBC only as “Wanksy” drew penis shapes around potholes. “They [potholes] don't get filled. They'll be there for months,” Wanksy said. “Suddenly you draw something amusing around it, everyone sees it and it either gets reported or fixed." The local city council spokesperson called the drawings “incredibly insulting.”

6. Tourist-friendly QR codes

It’s not as weird as the other entries on the list, but possibly more useful. Rio is known for its stunning beaches, spectacular Carnival, and the black-and-white sidewalk mosaics around the city known as Portuguese pavement. In 2013, the city began installing QR codes using the same black-and-white stone used to create decorative images of fish, waves, and vegetation. The city installed about 30 of the codes at beaches, scenic hotspots and historic sites, and tourists can use the codes alongside a smartphone app to get background information in Portuguese, Spanish, and English.

This list first appeared in 2016 and was republished in 2019.