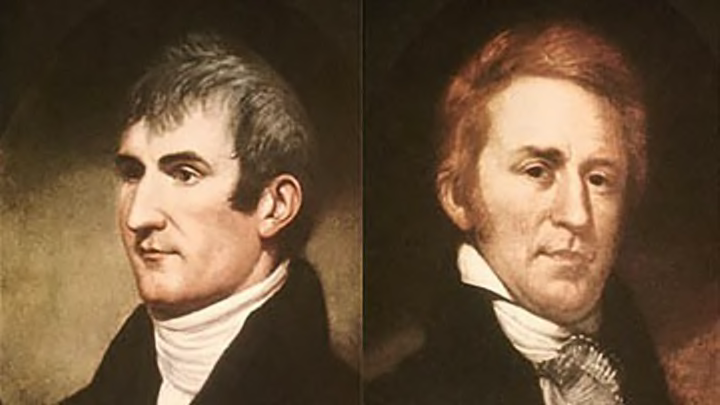

Between life-threatening accidents, hypothermia, diseases, and digestive problems, life in the wilderness wasn’t easy for Lewis and Clark. Thankfully, the two explorers had enough foresight and medical savvy to pack their trunks with mercury chloride, or calomel, before they left St. Louis and set off for the Pacific Coast.

Today’s doctors would shudder at the thought of patients ingesting what’s essentially mercury-poisoning-in-a-pill. But during the 18th century, calomel was a go-to drug for many conditions, including constipation. And sure enough, Lewis and Clark’s journals mention their men taking a popular remedy called Dr. Rush’s Bilious Pill—a fast-acting purgative that contained a whopping 10 grains of calomel per serving.

Centuries later, historians and archaeologists alike can thank Dr. Rush—and the explorers’ fiber-less diet—for helping them locate several of Lewis and Clark’s original campsites. By testing old latrine waste for mercury, they were able to distinguish which abandoned sites along their route served as a temporary homes for the famous adventurers. According to the Archaeological Institute of America, the expedition camped at more than 600 sites; several of them have been identified over the years thanks to their privy pits. Now, at sites like Travelers’ West, visitors can enjoy the same wildlife as their pioneer forefathers—if they’re not too busy being thankful for modern medicine.

[h/t: i09]