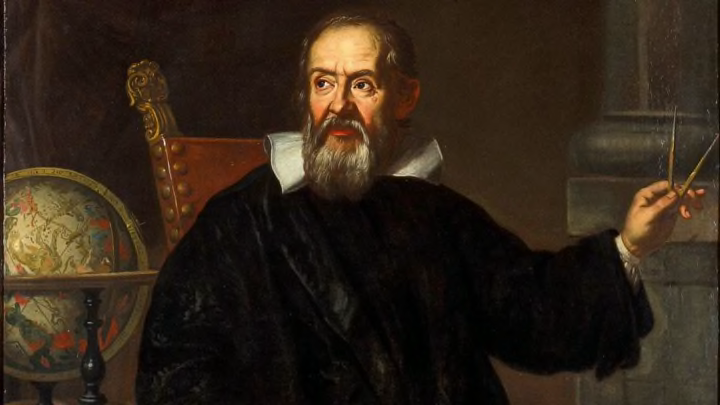

Albert Einstein once said that the work of Galileo Galilei “marks the real beginning of physics.” And astronomy, too: Galileo was the first to aim a telescope at the night sky, and his discoveries changed our picture of the cosmos. Here are 15 things that you might not know about the father of modern science.

1. There's a reason why Galileo Galilei's first name echoes his last name.

You may have noticed that Galileo Galilei’s given name is a virtual carbon copy of his family name. In her book Galileo’s Daughter, Dava Sobel explains that in Galileo’s native Tuscany, it was customary to give the first-born son a Christian name based on the family name (in this case, Galilei). Over the years, the first name won out, and we’ve come to remember the scientist simply as “Galileo.”

2. Galileo Galilei probably never dropped anything off the leaning tower of Pisa.

With its convenient “tilt,” the famous tower in Pisa, where Galileo spent the early part of his career, would have been the perfect place to test his theories of motion, and of falling bodies in particular. Did Galileo drop objects of different weights, to see which would strike the ground first? Unfortunately, we have only one written account of Galileo performing such an experiment, written many years later. Historians suspect that if Galileo took part in such a grand spectacle, there would be more documentation. (However, physicist Steve Shore did perform the experiment at the tower in 2009; I videotaped it and put the results on YouTube.)

3. Galileo taught his students how to cast horoscopes.

It’s awkward to think of the father of modern science mucking about with astrology. But we should keep two things in mind: First, as historians remind us, it’s problematic to judge past events by today’s standards. We know that astrology is bunk, but in Galileo’s time, astrology was only just beginning to disentangle from astronomy. Besides, Galileo wasn’t rich: A professor who could teach astrological methods would be in greater demand than one who couldn’t.

4. Galileo didn't like being told what to do.

Maybe you already knew that, based on his eventual kerfuffle with the Roman Catholic Church. But even as a young professor at the University of Pisa, Galileo had a reputation for rocking the boat. The university’s rules demanded that he wear his formal robes at all times. He refused—he thought it was pretentious and considered the bulky gown a nuisance. So the university docked his pay.

5. Galileo Galilei didn't invent the telescope.

We’re not sure who did, although a Dutch spectacle-maker named Hans Lipperhey often gets the credit (he applied for a patent in the fall of 1608). Within a year, Galileo Galilei obtained one of these Dutch instruments and quickly improved the design. Soon, he had a telescope that could magnify 20 or even 30 times. As historian of science Owen Gingerich put it, Galileo managed “to turn a popular carnival toy into a scientific instrument.”

6. A king leaned on Galileo to name planets after him.

Galileo rose to fame in 1610 after discovering, among other things, that the planet Jupiter is accompanied by four little moons, never previously observed (and invisible without telescopic aid). Galileo dubbed them the “Medicean stars” after his patron, Cosimo II of the Medici family, who ruled over Tuscany. The news spread quickly; soon the king of France was asking Galileo if he might discover some more worlds and name them after him.

7. Galileo didn't have trouble with the church for the first two-thirds of his life.

In fact, the Vatican was keen on acquiring astronomical knowledge, because such data was vital for working out the dates of Easter and other holidays. In 1611, when Galileo visited Rome to show off his telescope to the Jesuit astronomers there, he was welcomed with open arms. The future Pope Urban VIII had one of Galileo’s essays read to him over dinner and even wrote a poem in praise of the scientist. It was only later, when a few disgruntled conservative professors began to speak out against Galileo, that things started to go downhill. It got even worse in 1616, when the Vatican officially denounced the heliocentric (sun-centered) system described by Copernicus, which all of Galileo’s observations seemed to support. And yet, the problem wasn’t Copernicanism. More vexing was the notion of a moving Earth, which seemed to contradict certain verses in the Bible.

8. Galileo probably could have earned a living as an artist.

We think of Galileo as a scientist, but his interests—and talents—straddled several disciplines. Galileo could draw and paint as well as many of his countrymen and was a master of perspective—a skill that no doubt helped him interpret the sights revealed by his telescope. His drawings of the moon are particularly striking. As the art professor Samuel Edgerton has put it, Galileo’s work shows “the deft brushstrokes of a practiced watercolorist”; his images have “an attractive, soft, and luminescent quality.” Edgerton writes of Galileo’s “almost impressionistic technique” more than 250 years before Impressionism developed.

10. Galileo wrote about relativity long before Einstein.

He didn’t write about exactly the same sort of relativity that Einstein did. But Galileo understood very clearly that motion is relative—that is, that your perception of motion has to do with your own movement as well as that of the object you’re looking at. In fact, if you were locked inside a windowless cabin on a ship, you’d have no way of knowing if the ship was motionless, or moving at a steady speed. More than 250 years later, these ideas would be fodder for the mind of the young Einstein.

10. Galileo never married, but that doesn't mean he was alone.

Galileo was very close with a beautiful woman from Venice named Marina Gamba; together, they had two daughters and a son. And yet, they never married, nor even shared a home. Why not? As Dava Sobel notes, it was traditional for scholars in those days to remain single; perceived class difference may also have played a role.

11. You can listen to music composed by Galileo's dad.

Galileo’s father, Vincenzo, was a professional musician and music teacher. Several of his compositions have survived, and you can find modern recordings of them on CD (like this one). The young Galileo learned to play the lute by his father’s side; in time he became an accomplished musician in his own right. His music sense may have aided in his scientific work. With no precision clocks, Galileo was still able to time rolling and falling objects to within mere fractions of a second.

12. Galileo's discoveries may have influenced a scene in one of Shakespeare's late plays.

An amusing point of trivia is that Galileo and Shakespeare were born in the same year (1564). By the time Galileo aimed his telescope at the night sky, however, the English playwright was nearing the end of his career. But he wasn’t quite ready to put down the quill: His late play Cymbeline contains what may be an allusion to one of Galileo’s greatest discoveries—the four moons circling Jupiter. In the play’s final act, the god Jupiter descends from the heavens, and four ghosts dance around him in a circle. It could be a coincidence—or, as I suggest in my book The Science of Shakespeare, it could hint at the Bard's awareness of one of the great scientific discoveries of the time.

13. Galileo had some big-name visitors while under house arrest.

Charged with “vehement suspicion of heresy,” Galileo spent the final eight years of his life under house arrest in his villa outside of Florence. But he was able to keep writing and, apparently, to receive visitors, among them two famous Englishmen: the poet John Milton and the philosopher Thomas Hobbes.

14. Galileo's bones have not rested in peace.

When Galileo died in 1642, the Vatican refused to allow his remains to be buried alongside family members in Florence’s Santa Croce Basilica; instead, his bones were relegated to a side chapel. A century later, however, his reputation had improved, and his remains (minus a few fingers) were transferred to their present location, beneath a grand tomb in the basilica’s main chapel. Michelangelo is nearby.

15. Galileo might not have been thrilled with the Vatican's 1992 "apology."

In 1992, under Pope John Paul II, the Vatican issued an official statement admitting that it was wrong to have persecuted Galileo. But the statement seemed to place most of the blame on the clerks and theological advisers who worked on Galileo’s case—and not on Pope Urban VIII, who presided over the trial. Nor was the charge of heresy overturned.

Additional sources: The Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo; Galileo's Daughter; The Cambridge Companion to Galileo.