A new app could turn the world’s 3 billion smartphones into a massive seismic network, listening for tiny tremors and improving our earthquake early warning capability.

Up until now, researchers have considered using smartphone GPS to measure large ground movement—but if you’ve ever taken a long road trip, you know the effect this would have on battery life. Now, researchers from the University of California, Berkeley have partnered with Deutsche Telekom to develop an app that works effectively without draining the battery, and can help improve earthquake detection without new infrastructure.

“The idea is to take advantage of the millions of smartphone accelerometers that already exist,” Richard Allen, director of UC Berkeley's Seismological Laboratory, said on February 11 at a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C.

The app is called MyShake, and it uses a carefully designed algorithm that can sift through the background noise of your normal physical activity, and distinguish the faint seismic signals that can precede a quake.

The idea is that given a big enough network of smartphones, real-time earthquake estimates can start to unfold.

The app, available for download today, beams the network data to a central server, which analyzes it in real time and calculates the quake location, origin time, and magnitude. Then, it can estimate the intensity of shaking and the amount of time before damaging waves arrive at a given point. It can detect quakes upwards of magnitude 5, as much as 6.2 miles away.

The scientists tested it by simulating the magnitude 5.1 La Habra earthquake in Los Angeles in 2014, and comparing MyShake response time and magnitude estimate with those of the existing ShakeAlert, an early warning system developed by the U.S. Geological Survey and several university partners—including UC-Berkeley—that has been in testing for the past four years. MyShake performed better than ShakeAlert.

It was just a simulation, but the potential is huge. Consider California alone: It has a dense network of 400 traditional seismic stations to track almost constant tectonic activity. It also has 16 million smartphone users. The data from their phones could massively improve our ability to detect earthquakes and send out warnings quicker.

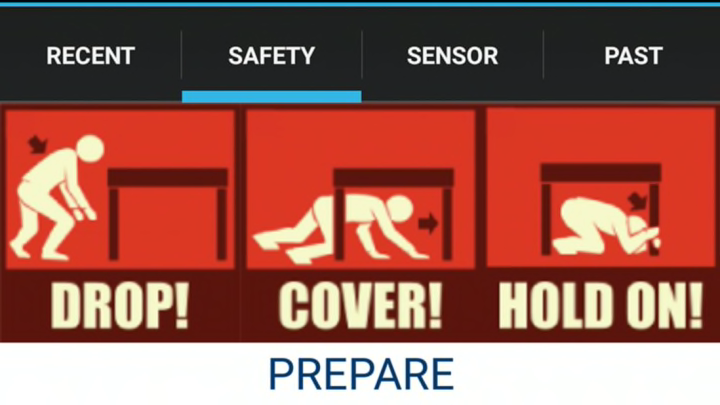

Screenshot from MyShake

The system isn’t meant to be a substitute for traditional earthquake sensors. “A smartphone will never replace a traditional seismic station,” Allen emphasized. Instead, the researchers hope MyShake can augment existing monitoring systems, and see a big role for it in areas without detection infrastructure.

One potential spot for its use is Nepal. When the country was hit by a magnitude 7.8 quake in April 2015, it had no earthquake detection stations—but it did have 6 million smartphone users. The scientists think that if MyShake technology had been available, the 600,000 smartphones in Katmandu could’ve generated a warning as much as 20 seconds before the big shaking began—and perhaps avoided some of the thousands of deaths that resulted from the quake.

Twenty seconds doesn’t sound like much, but according to disaster prevention researcher Masumi Yamada, of Kyoto University, who also spoke at the presentation, tens of seconds is pretty standard for an early warning system. Japan’s seismic network is even denser than California’s, and a warning system has been operating there since 2007. In 2011, it issued a warning within seconds when the magnitude 9 Tohoku quake began, saving lives.

Even a few seconds can be enough to slow or stop transit and heavy machinery, or halt surgeries—and in developing regions like Nepal, where building safety codes are poor or nonexistent, it offers precious time for people to simply get outside, clear of buildings that could come down on top of them.

The app also includes safety tips and information on past earthquakes in the local region. And like most scientific efforts, a mobile seismic network requires teamwork. It needs users in areas that aren’t tectonically active, so the algorithm can better distinguish the difference between ordinary human movement and actual shaking. So even if you don’t live in a seismically active area, consider downloading the app at Google Play. It could help reduce the impact of future seismic hazards by contributing data that helps researchers better understand earthquake physics.

When it comes to being prepared for The Big One—a quake like the one predicted to destroy the Pacific Northwest one day—Allen said, "Are we ready? The answer is no, we’re not ready. But I’m very hopeful that here in the U.S., we might actually be able to implement an earthquake early warning system before we have the next big earthquake. We’re making progress.”