Astronomers have discovered a record-breaking stellar eclipse in a binary star system far, far away. Every 69 years the newly discovered system, known only as TYC 2505-672-1, is shrouded in darkness for nearly 3.5 years. According to a study forthcoming in Astronomical Journal, it is both the longest eclipse duration and the longest period between eclipses ever recorded.

The researchers say that TYC 2505-672-1 broke the record previously held by Epsilon Aurigae, a star that is eclipsed every 27 years for up to 730 days. "Epsilon Aurigae is much closer - about 2200 light-years from Earth - and brighter, which has allowed astronomers to study it extensively," explains study first author Joey Rodriguez.

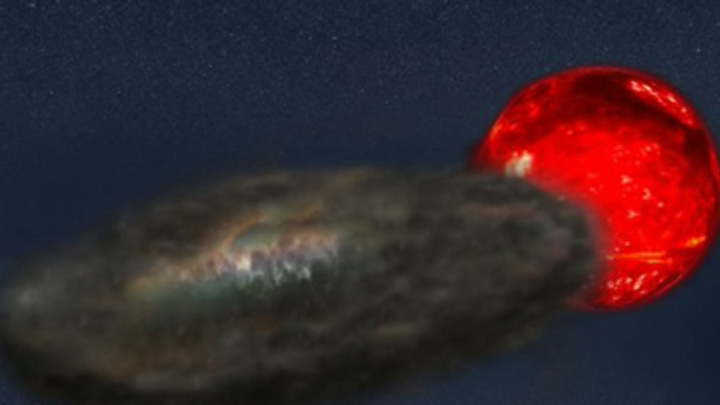

By contrast, TYC 2505-672-1 is nearly 10,000 light-years from Earth, and more difficult to observe. Researchers believe the two stars in the system are red giants - one a primary star, and the other a "stripped" companion star with a relatively smaller core surrounded by an extremely large disk of material that may produce the eclipse. This companion star is close to 2000 degrees C hotter than the Sun. To account for the long interval between eclipses, the researchers think the stars are likely orbiting at a distance of 20 astronomical units (about the distance between the Sun and Uranus).

Astronomer Keivan Stassun explains that the star system presents a unique opportunity for researchers. Many astronomical phenomena occur so far away and over such a long time that they're difficult to observe in a single human lifespan. But in the case of TYC 2505-672-1, astronomers have been able to draw on a century of data collected by researchers at Harvard University between 1890 and 1989.

"One of the great challenges in astronomy is that some of the most important phenomena occur on astronomical timescales, yet astronomers are generally limited to much shorter human timescales," Stassun explains. "Here we have a rare opportunity to study a phenomenon that plays out over many decades and provides a window into the types of environments around stars that could represent planetary building blocks at the very end of a star system's life."