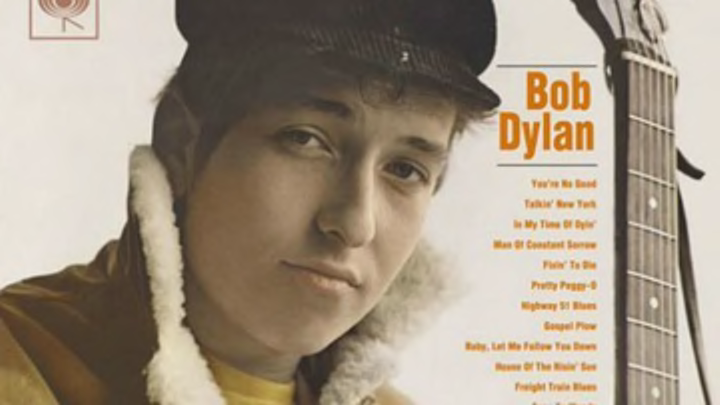

Bob Dylan’s eponymous debut album, released on March 19, 1962, is Dylan before he became Dylan. The 20-year-old folk singer had clocked less than a year in New York City by the time he recorded it. Only two original songs are on the album, alongside 11 recordings of classic folk songs. Here are 10 facts about Bob Dylan, an album that only took two afternoons to record.

1. A POSITIVE NEW YORK TIMES REVIEW HELPED PUT DYLAN ON THE MAP

Robert Shelton, the folk music critic for The New York Times, was impressed by Dylan’s performances at house parties and hootenannies. According to Clinton Heylin’s biography of Dylan, Behind the Shades, the young Minnesota transplant pestered Shelton to write about him, but Dylan didn’t have a gig Shelton saw as worthy of the Times' attention until September 1961, when he opened for the Greenbriar Boys at Gerde’s Folk City. Shelton wrote a glowing review.

“Resembling a cross between a choir boy and a beatnik, Mr. Dylan has a cherubic look and a mop of tousled hair he partly covers with a Huck Finn black corduroy cap,” wrote Shelton. “His clothes may be in need of a bit of tailoring, but when he works his guitar, harmonica or piano and composes new songs faster than he can remember them, there is no doubt that he is busting at the seams with talent.”

Accounts vary about to what degree the review prompted Columbia Records executive John Hammond (who had already had been keeping tabs on Dylan) to offer the artist a five-year contract, but Dylan was signed by the record company shortly after the performance.

2. THE ADVANCE ALLOWED DYLAN TO GET HIS OWN APARTMENT

The singer/songwriter was sleeping on couches and staying with a series of friends in the folk music scene, according to Heylin. He moved to 161 West 4th Street, and the photo for the cover of his second studio album, 1963's The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, was shot around the corner.

3. DYLAN WROTE JUST TWO SONGS FOR THE ALBUM

As was typical before Dylan himself helped usher in the age of the singer/songwriter, most of the songs were takes on well-known standards. His own “Talkin’ New York” is a “talking blues” song about his early life in Greenwich Village. The line about “blowin’ my lungs out for a dollar a day” was likely a reference to his gig playing harmonica on Carolyn Hester’s third album. “Song to Woody” is a tribute to his idol, Woody Guthrie, whom he met shortly after arriving in the city.

4. DYLAN WROTE "SONG TO WOODY" IN A BLEECKER STREET BAR

The handwritten lyrics for the song wound up with Bob Gleason and his wife, Sidsel, a New Jersey couple who were friends with Guthrie and often hosted his Sunday get-togethers with emerging folk singers. They include the inscription: “Written by Bob Dylan in Mills Bar on Bleecker Street in New York City on the 14th day of February, for Woody Guthrie.”

5. IT WAS RECORDED OVER TWO AFTERNOONS

Hammond and Dylan used a studio in Columbia’s New York City headquarters and cut the album on November 20 and 22, 1961. Dylan was unaccompanied, musically. Dylan and Hammond recorded 17 songs and did only one take each. “Mr. Hammond asked me if I wanted to sing any of them over again and I said no,” Dylan said in 1962. “I can’t see myself singing the same song twice in a row.”

6. COLUMBIA'S PRESIDENT STOPPED BY, BUT DYLAN WAS MORE CONCERNED WITH IMPRESSING THE JANITOR

Goddard Lieberson, president of Columbia and a longtime friend of Hammond, stopped by and voiced his approval from the engineer’s booth. According to No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan by The New York Times’ Robert Shelton, Dylan found it more important that an elderly African-American janitor stopped his work to listen to him play “Fixin’ to Die,” a song popularized by blues singer Bukka White. According to Shelton, "It impressed [Dylan] more than anything Hammond or Lieberson said."

7. IT SOUNDS BETTER IN MONO

Hammond used just two microphones: one on Dylan’s voice and one on his guitar. Because of this, “[m]any hardcore fans will only listen to the record in mono,” writes Brian Hinton in Bob Dylan Complete Discography. “[T]he stereo separation of this album is brutal, with vocal and guitar each occupying a virtual exclusive zone.”

8. SHELTON HELPED OUT WITH THE LINER NOTES

Hammond enlisted Dylan's first reviewer, Robert Shelton, to write the liner notes for Bob Dylan. “The Times music department had an unwritten code that members should have nothing to do with the production of recordings that they might review,” Shelton wrote in No Direction Home. “But nearly every member earned supplementary income by writing liner notes, anonymously or pseudonymously.” As “Stacey Williams,” Shelton wrote that Dylan’s steel-string playing “runs strongly in the blues vein, although he will vary it with country configurations.”

9. DYLAN'S GIRLFRIEND AT THE TIME DISPUTED A TIDBIT FROM THE LINER NOTES

While Shelton wrote in the liner notes that Dylan's girlfriend Suze Rotolo lent the singer her lipstick holder to use as a bottleneck during the recording sessions, Rotolo disputes this claim. "I didn't wear lipstick," she wrote in her 2008 memoir, A Freewheelin' Time.

10. IT FAILED TO CHART

Bob Dylan flopped, and around the Columbia offices the young singer began to be known as “Hammond’s Folly.” By the time it was released, Dylan had already changed his focus to original material, according to Hinton's Bob Dylan Complete Discography. That April, Bob Dylan sat down in a café and began work on “Blowin’ in the Wind.”