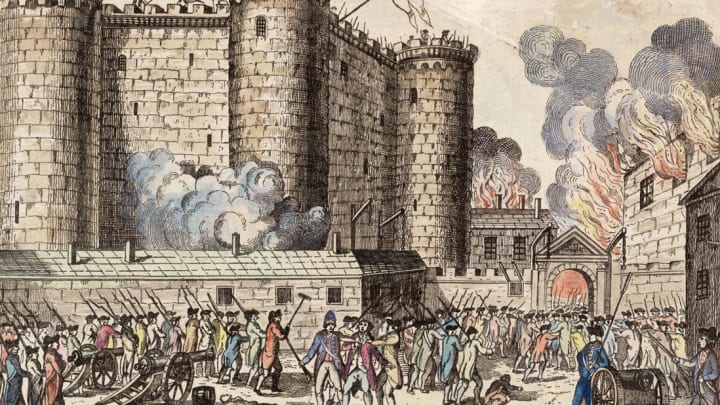

On July 14, 1789, Parisian revolutionaries stormed the Bastille fortress, where Louis XVI had imprisoned many of his enemies—or those whom he perceived to be enemies of the state. For many, the place had come to represent nothing short of royal tyranny. Its sudden fall foretold the French revolution, along with a holiday that’s now celebrated throughout France and the world at large with cries of “Vive le 14 Juillet!”

1. In France, nobody calls it "Bastille Day."

The day is referred to as la Fête Nationale, or “the National Holiday.” In more informal settings, French people also call it le Quatorze Juillet (“14 July”). "Bastille Day" is an English term that’s seldom used within French borders—at least by non-tourists.

2. Originally, the Bastille wasn't designed to be a prison.

The name “Bastille” comes from the word bastide, which means “fortification,” a generic term for a certain type of tower in southern France until it was eventually restricted to one particular Bastille. When construction began on the building in 1357, its main purpose was not to keep prisoners in, but to keep invading armies out: At the time, France and England were engaged in the Hundred Years’ War. The Bastille, known formally as the Bastille Saint-Antoine, was conceived as a fortress whose strategic location could help stall an attack on Paris from the east.

Over the course of the Hundred Years' War, the structure of the building changed quite a bit. The Bastille started out as a massive gate consisting of a thick wall and two 75-foot towers. By the end of 1383, it had evolved into a rectangular fortress complete with eight towers and a moat.

Such attributes would later turn the Bastille into an effective state prison—but it wasn’t actually used as one until the 17th century. Under King Louis XIII, the powerful Cardinal de Richelieu began the practice of jailing his monarch’s enemies (without a trial) inside; at any given time, the cardinal would hold up to 55 captives there.

3. The Bastille was loaded with gunpowder.

In July 1789, France was primed for a revolt. Bad weather had driven food prices through the roof, and the public resented King Louis XVI’s extravagant lifestyle. To implement financial reforms and quell rebellion, Louis was forced to call a meeting of the Estates-General, a national assembly representing the three estates of France. The First Estate was the clergy, the Second Estate held the nobility, and all other royal subjects comprised the Third Estate. Each estate had a single vote, meaning two estates could defeat the other estate every time.

The Estates-General met in Versailles on May 5, 1789. Arguments between the Third Estate and the other two boiled over on June 20. King Louis responded by physically locking the common people’s representatives out of the room. The third estate, now calling themselves the National Assembly, reconvened on an indoor tennis court and pledged to remain active until a French constitution was established.

The King sanctioned the National Assembly on June 27, but then sent troops into Paris to deal with growing unrest. He made his problems worse by dismissing finance official Jacques Necker, who supported the Third Estate. The National Assembly and everyday citizens began to take up arms. On July 14, 1789, revolutionaries burst into a soldiers’ hospital in Paris and seized 3000 guns and five cannons. Then, they broke into the Bastille where a stockpile of gunpowder lay.

4. The July 14 "storming" freed only a handful of prisoners ...

The French revolutionaries who broke into the Bastille expected to find numerous inmates. In reality, the prison was almost empty except for seven captives who seemed to be in relatively good health. We may never be certain of their identities. Some accounts claim that four of the prisoners had committed forgery, two were regarded as lunatics, and one was a disgraced nobleman. Other sources are less specific. A report penned on July 24 agrees that four were forgers and another came from an aristocratic family—but that the other two vanished before anyone could definitively identify them.

5. ... and the Marquis de Sade was almost among them.

You probably know him as the man whose conduct and erotic writings gave rise to the word sadism. In 1784, the aristocrat was transferred from another prison to the Bastille, where he languished for the next five years. Within those walls, de Sade penned several books—including his notorious novel One Hundred and Twenty Days of Sodom.

He surely would have been freed when the Bastille was stormed. But on June 2, de Sade started yelling at the passersby beneath his window, claiming that people were being maimed and killed inside and begging the people to save him. The episode got de Sade transferred once again—this time to an insane asylum outside Paris. His removal from the Bastille took place on July 4, 1789. Ten days later, rebels stormed inside.

6. Thomas Jefferson donated money to the families of the revolutionaries.

As America’s minister to France (and a big fan of revolution), Jefferson took a lively interest in the Bastille incident, which broke out while he was living abroad in Paris. Although Long Tom didn’t witness the event firsthand, he eloquently summarized everything he’d learned about the siege in a detailed letter to John Jay. On August 1, 1789, Jefferson wrote in his diary, “Gave for widows of those killed in taking Bastille, 60 francs.”

7. A huge festival was held exactly one year after the Bastille was stormed.

By July 14, 1790, the Bastille had been destroyed, its pieces scattered across the globe by souvenir collectors. France now operated under a constitutional monarchy, an arrangement that divided power between King Louis XVI and the National Assembly. Meanwhile, hereditary nobility was outlawed.

To honor these advances, the government organized a huge event called the “Festival of the Federation,” which was to take place on the first anniversary of the Bastille showdown. As July 14 approached, French citizens from all walks of life came together and set up some 40,000 seats in preparation. When the big day finally arrived, King Louis arrived with 200 priests and swore to maintain the constitution. The Marquis de Lafayette—who’d famously helped orchestrate America’s revolution—stood by the monarch’s side. Later on, Queen Marie Antoinette got a huge cheer when she proudly showed off the heir apparent. Among the spectators was dramatist Louis-Sébastien Mercier, who later said, “I saw 50,000 citizens of all classes, of all ages, of all sexes, forming the most superb portrait of unity."

8. Several different dates were considered for the French national holiday.

Here’s a trick question: What historical event does Bastille Day commemorate? If you answered “the storming of the Bastille prison,” you’re both right and wrong. In 1880, France’s senate decided that their homeland needed a national holiday. What the French statesmen had in mind was an annual, patriotic celebration dedicated to the country and its citizens. But the matter of choosing a date turned into an extremely partisan ordeal: Every available option irked somebody in the senate on ideological grounds. For instance, conservatives were dead-set against July 14 (at least at first) because they felt that the 1789 Bastille incident was too bloody to merit celebration.

Alternatives were numerous. To some, September 21 looked attractive, since the original French Republic was created on that day in 1792. Others favored February 24, which marked the birth of France’s second republic. Another option was August 4, the anniversary of the feudal system’s abolishment.

Ultimately, though, July 14 managed to win out. After all, the date marks not one but two very important anniversaries: 1789’s attack on the Bastille and 1790’s peaceful, unifying Festival of the Federation. So by choosing July 14, the senate invited all citizens to decide for themselves which of these events they’d rather celebrate. As Senator Henri Martell argued, anyone who had reservations about the first July 14 could still embrace the second. Personally, he revered the latter. In his own words, July 14, 1790 was “the most beautiful day in the history of France, possibly in the history of mankind. It was on that day that national unity was finally accomplished.”

9. Bastille Day features the oldest and largest regular military parade in Western Europe.

This beloved Paris tradition dates all the way back to 1880. In its first 38 years, the parade’s route varied wildly, but since 1918, the procession has more or less consistently marched down the Champs-Elysées, the most famous avenue in Paris. Those who watch the event in person are always in for a real spectacle—the 2019 parade boasted some 39 helicopters, 69 planes, and 4000 soldiers. It’s also fairly common to see troops from other nations marching alongside their French counterparts. In 2015, for example, 150 Mexican soldiers came to Paris and participated.

10. In France, firemen throw public dances on Bastille Day.

On the night of July 13 or 14, people throughout France live it up at their local fire departments. Most stations throw large dance parties that are open to the entire neighborhood (kids are sometimes welcome). Please note, however, that some fire departments charge an admission fee. Should you find one that doesn’t, be sure to leave a donation behind instead. It’s just common courtesy.

11. The Louvre celebrates Bastille Day by offering free admission.

If you’re in Paris on Bastille Day and don’t mind large crowds, go say bonjour to the Mona Lisa. Her measurements might surprise you: The world’s most famous painting is only 30 inches tall by 21 inches wide.

12. Bastille Day has become a truly international holiday.

Can’t get to France on Bastille Day? Not a problem. People all over the world honor and embrace the holiday. In eastern India, the scenic Puducherry district was under French rule as recently as 1954. Every July 14, fireworks go off in celebration and a local band usually plays both the French and Indian national anthems (though 2021's festivities may be postponed). Thousands of miles away, Franschhoek, South Africa, usually throws an annual, two-day Bastille celebration—complete with a parade and all the gourmet French cuisine you could ask for. However, it looks like they're skipping the 2021 edition and will be back in 2022.

13. A huge solar flare once took place on Bastille Day.

NASA won’t be forgetting July 14, 2000, anytime soon. On that particular day, one of the largest solar storms in recent memory caught scientists off guard. An explosion caused by twisted magnetic fields sent a flurry of particles racing toward Earth. These created some gorgeous aurora light shows that were visible as far south as El Paso, Texas. Unfortunately, the particles also caused a few radio blackouts and short-circuited some satellites. Astronomers now refer to this incident as “The Bastille Day Event.”

14. You can find a key to the Bastille at Mount Vernon.

The Marquis de Lafayette, 19, arrived in the new world to join America’s revolutionary cause in 1777. Right off the bat, he made a powerful friend: George Washington instantly took a liking to the Frenchman and within a month, Lafayette had effectively become the general’s adopted son. Their affection was mutual; when the younger man had a son of his own in 1779, he named him Georges Washington de Lafayette.

The day after the storming of the Bastille, the Marquis de Lafayette became the commander of the Paris National Guard. In the aftermath of the Bastille siege, he was given the key to the building. As a thank-you—and to symbolize the new revolution—Lafayette sent it to Washington’s Mount Vernon home, where the relic still resides today

A version of this story ran in 2017; it has been updated for 2021.