Archaeologists in Illinois say a prominent pre-Columbia burial mound in the famous ancient city of Cahokia was hardly a monument to masculinity, as their predecessors in the 1960s had claimed. They published their findings in several journals, including American Antiquity.

A thousand years ago, the complex cities and suburbs of Mississippian peoples sprawled across the Midwest. Cahokia, the largest urban center, lay just across the river from modern-day St. Louis. At its peak in the 13th century, it rivaled London in size. Then, over time, like so many civilizations do, it vanished.

But the Mississippians were builders of mounds, whose works left large, hard-to-miss marks on the landscape. French and Spanish explorers first spotted Cahokia’s burial mounds in the 1500s, and we’ve been unearthing its secrets ever since.

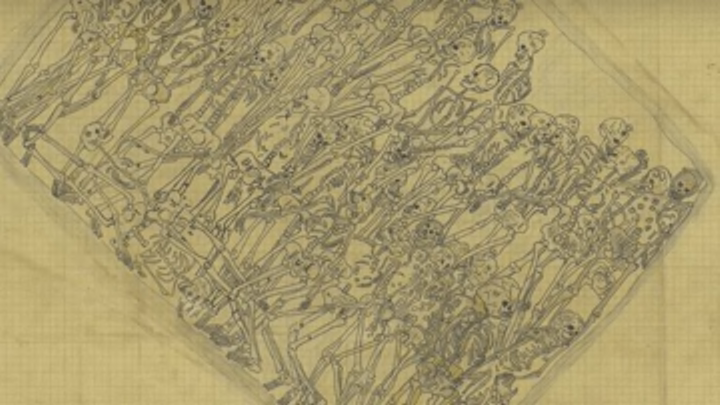

Much of what we know today about Cahokia culture comes from the work of one man. Archaeologist Melvin Fowler was digging at the site in 1967 when he uncovered an enormous burial ground. The area known today as Mound 72 yielded five mass graves and dozens of scattered individual resting places, containing a total of 270 people who had been buried between 1000 CE and 1200 CE. But not all the dead had been treated equally. Two bodies in particular seemed to have been accorded special care. They were stacked, one atop the other, in a bed of beads, and surrounded by the painstakingly arranged bodies of four people who had died at the same time.

To Fowler, the beads between the bodies and those scattered by their heads appeared to form the shapes of birds. Fowler knew that birds were associated with warriors and supernatural powers in some Native American traditions, and so he concluded that the two central figures must have been legendary warrior chiefs. The bodies buried with them must have been servants, there to glorify their leaders’ manly feats.

Nobody corrected him. Over time, the theory that Cahokia was a hierarchical he-man culture became accepted fact. And it might have stayed that way, had modern archaeologists not decided to double-check Fowler’s findings. They took a closer look at their predecessors’ notes and maps, then continued to explore the site. They found more bodies right off the bat; the beaded burial, as it’s come to be known, contained 12 bodies, not 6.

They took bone and tooth samples from the bodies and tested them to see if they could determine the approximate ages of the deceased. That’s when they realized that a lot of the bodies were not men at all. One of the so-called warrior men was a woman, and other stacked pairs nearby were male-female as well. The mass graves had plenty of women in them. Nearby, they even found the remains of a child.

Julie Mahon

Co-author Thomas Emerson is the director of the Illinois State Archaeological Survey. He says the inclusion of women in these high-status burial sites pretty much tosses Fowler’s male supremacist theory out the window.

"Now, we realize, we don't have a system in which males are these dominant figures and females are playing bit parts,” he said in a press statement. “And so, what we have at Cahokia is very much a nobility. It's not a male nobility. It's males and females, and their relationships are very important."

Emerson says including higher-class women in Mound 72 is consistent with other burial rituals in the area. All around Cahokia, he says, he found symbols of “life renewal, fertility, agriculture. Most of the stone figurines found there are female.”

Fowler and his contemporaries mistakenly assumed that there was one Native American culture rather than a variety of cultures, regardless of time or place. "People who saw the warrior symbolism in the beaded burial were actually looking at societies hundreds of years later in the southeast, where warrior symbolism dominated, and projecting it back to Cahokia and saying: 'Well, that's what this must be,'" Emerson said. "And we're saying: 'No, it's not.'"

Know of something you think we should cover? Email us at tips@mentalfloss.com.