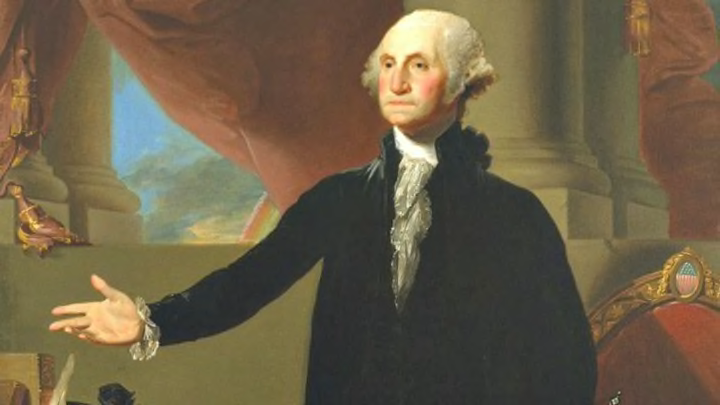

The story of First Lady Dolley Madison heroically saving a portrait of George Washington as she was being exiled from the White House during the War of 1812 has been circulated for centuries.

The tale isn’t quite that simple, though. If you’re envisioning Dolley tearing the famous Gilbert Stuart portrait down as the Red Coats closed in and the curtains burned, well, that’s not quite what happened. Madison actually instructed an enslaved servant, 15-year-old Paul Jennings, to save the painting. “If not possible, destroy it: under no circumstance allow it to fall into the hands of the British,” she told him. The painting was 8 feet by 5 feet, so getting it off the wall was no easy task. With time running out, however, Jennings didn’t exactly have the luxury of carefully removing the frame from the wall and gently packing it away. Instead, he had to splinter the wood and cut the canvas out. It worked, and the painting was successfully smuggled out of the White House.

WikimediaCommons // Public Domain

All of that risk, all of that effort—and it turns out that the work was a mere copy. The original portrait of Washington—known as the Lansdowne portrait, because it was a gift for the Marquis of Lansdowne—was privately owned for decades. It’s believed that Stuart painted another three copies of this original work, and other artists painted more versions still to be hung in government offices across the country.

Some experts say the painting saved by Jennings on that chaotic night back in 1814 was one of these knock-offs. “The painting is not by Gilbert Stuart,” former National Portrait Gallery director Marvin Sadik told ARTnews in 1975.

Stuart himself didn’t do much to help clear up the matter. In 1802, he reportedly said, “I did not paint it, but I bargained for it.” His vague comment is open to interpretation: Some historians believe he was embarrassed by the quality of that particular copy and wasn’t too keen to claim it as his own. Others think that this copy was intended for (and already paid for by) Charles Pinckney, America's then-new minister to France. Stuart may have sold the painting to someone else, accepted a fee from both parties, then denied that he had anything to do with it in order to cover his tracks.

But whether the portrait saved by Dolley Madison and Paul Jennings was painted by Stuart’s hand or that of a lesser known artist, it was still just a copy of the original Lansdowne portrait. That original is usually on display at the National Portrait Gallery, not far from the version of the painting that was saved from the British—that copy is still displayed in the East Room of the White House. There’s one easy way to identify this particular iteration: The artist included a “typo” to set it apart from the others. If you look closely at the books by the table leg, you can see that one is titled The Constitution and Laws of the United Sates.

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain