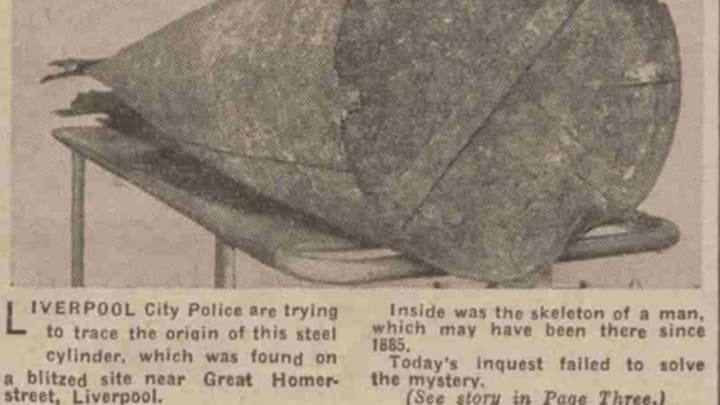

Around 1941, the Germans dropped a bomb on a street in Liverpool, exposing among the rubble a watertight metal cylinder about 6.5 feet long. For several years it lay on the side of the street, more or less ignored. People used it as a bench, kids played on it, and nobody thought it was anything particularly unusual—until one day somebody took a look inside.

Liverpool had been the most heavily bombed British city outside London during the Blitz. Much of the city was destroyed, and amid the chaos, the explosion on Great Homer Street seemed just like any other. Rubble had been cleared away by American soldiers in bulldozers, who left behind some larger chunks of debris, including the aforementioned cylinder—which went largely ignored until July 13, 1945.

On that day, a group of children managed to break part of the cylinder open and peer inside. What they saw inside likely chilled them to the core: a corpse.

The police were alerted, and the cylinder was opened fully to reveal the skeleton of a man who, many locals presumed, had perished in the bombings a few years earlier. Curiously, however, the man was dressed head-to-toe in clothing much more suited to the Victorian era and lying on some sort of cloth. He also still had a few strands of hair attached to his skull, which was propped up on a makeshift pillow formed of a brick wrapped in burlap.

Rumors, speculation, and confusion surrounded the first few days of the discovery, with local newspaper the Evening Express stating that “at the present stage there did not seem to be any suggestion of murder. It was quite possible that the man was of the ‘queer’ type and had crawled into the cylinder to sleep. He may have been dead 20 years.” (In this context, queer likely meant somebody with a mental illness.) The mystery deepened a few days later, when the coroner, one Mr. G. C. Mort, announced that along with the body they had discovered two diaries (sadly illegible), a postcard, and a rail notice, all dating from 1884 or 1885, as well as a well-worn signet ring, a set of keys, and an undated receipt from a T. C. Williams and Co.

An investigation by the coroner showed that T. C. Williams and Co. had been a local paint manufacturing company that operated from the 1870s until 1884, when the company fell into financial ruin and closed for good. Its owner, Thomas Cregeen Williams, was declared bankrupt in 1884. Creditors were asked repeatedly to come forward and stake their claim to his assets, but by 1885 Williams had disappeared. Local papers announced the mystery solved—but the coroner wasn’t so sure. Williams had a son, born in 1859, and some believed that it was actually his body in the cylinder. This theory was ruled out when the investigation found the younger Williams buried in a cemetery in Leeds. Meanwhile, the elder Williams’s whereabouts remained unconfirmed.

As outlandish as it may seem that a body could lay undiscovered in residential Liverpool for 60 years, as far as the police were concerned, that appeared to have been what happened. On August 31, 1945, the official inquest recorded an open verdict, meaning the death was deemed suspicious but without an obvious cause. According to the Liverpool Evening Express, the coroner said it was "impossible to find the cause of death, which he believed took place in 1885.” Although the body in the cylinder has never been officially confirmed as that of T. C. Williams, this still stands as the prevailing theory.

But what of the cylinder? And how did the body end up in there in the first place? According to an official from the Home Office in 1945, the cylinder seemed to be part of a ventilation system (no traces of paint were found inside, ruling out any chance of a freak paint manufacturing accident). Was T. C. Williams sleeping in the vents of his old factory to hide from the creditors, and had he succumbed to deadly fumes? (The cylinder was found about a mile from the factory, but the bombs and bulldozers might have moved it.) Did he, as one theory put forward by the blog Strange Company suggests, fake his own death using this body as a decoy while making a break for America? Being that Liverpool was a major port city in the 1880s, it’s not logistically impossible, if perhaps a little farfetched. We might never know for sure. Perhaps the answer is still lying at the side of a road in Liverpool somewhere, just waiting to be noticed.