In 14 novels by comic author P.G. Wodehouse, written over the course of a half-century, a fictional valet named Reginald Jeeves fielded questions of sartorial, societal, and personal etiquette posed by his employer, wealthy London socialite Bertie Wooster.

By the late 1990s, Jeeves was being asked where internet users could find nude photos of actresses.

It should be noted that the Jeeves of the Wodehouse books, which were eventually used as a template for the BBC series Jeeves and Wooster, was not quite the same Jeeves of AskJeeves.com, the web portal that debuted in 1997 and encouraged search engine users to field their curiosity in the form of a question. (“What’s the best restaurant in San Diego?” “What is Pamela Anderson’s home address?”) But enough similarities remained for the Wodehouse estate to toy with the idea of litigation in 2000, asserting the dot-com had co-opted the character without any financial arrangement.

That would prove to be the least of the site’s problems. After a spectacular initial public offering (IPO) on the stock market that rocketed from $14 to $190.50 a share, Ask Jeeves became a casualty of the search engine wars of the early 2000s. Eventually, their mascot would be escorted right out the door.

Human Touch

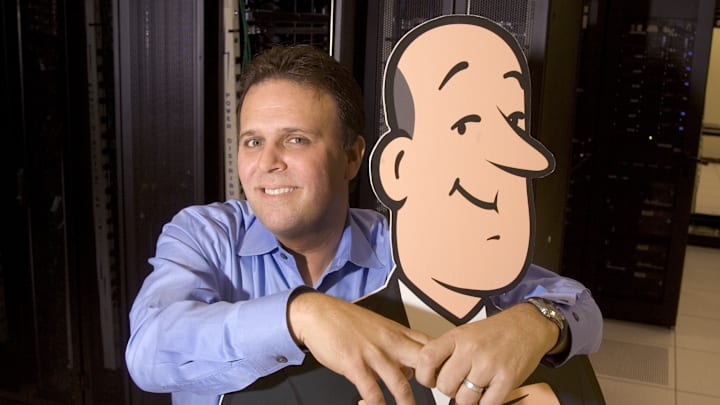

Long before Apple’s Siri and Amazon’s Alexa, Garrett Gruener had a notion to humanize information-gathering online. Gruener, a graduate of UC San Diego, had been a venture capitalist in the burgeoning computing world of the 1980s. After founding and selling off Virtual Microsystems in the 1980s, he looked for other ways to explore the market and the potential of the internet to become a consumer-friendly user space.

By 1992, Gruener had an interface, but no face to put to it. He liked the idea of a virtual concierge, similar to the hotel employee who fields guest requests, but didn’t think Americans would know exactly what the word meant. He went with a butler motif instead, and named him Jeeves—not after the Wodehouse character, he claimed, but more in line with how the name had become synonymous with servitude. In partnership with his former Virtual Microsystems employee David Warthen, Gruener launched Ask Jeeves in April 1997.

Although Yahoo!, Alta Vista, and Excite were already in the market, Gruener felt Ask Jeeves set itself apart with its interface. His team had spent months building a library of “knowledge capsules,” snapshots of answers to questions they felt would be most commonplace. If a question wasn’t addressed in their content, the site would default to a more general search.

For users overwhelmed with pages of results stemming from a simple search, Ask Jeeves was more refined—dignified, even—with Jeeves standing at attention near the search bar. Many of the queries were consumer-oriented—asking for the best eateries, plumbers, or hotels—while others sought the kind of information that required both urgency and specialized knowledge. “How to get rid of skunk smell?” was one common query. (Salaciousness won the day, however; one in five questions pertained to finding nude photos.)

Gruener’s hunch was correct. People enjoyed the direct, personalized navigation, and saw themselves as Ask Jeeves loyalists. He once compared them to Mac users, who had tunnel vision when it came to alternatives. By 1998, the site was handling 300,000 searches a day. By 1999, it was up to 1 million. After going public, shares climbed from $14 to $60 to $190.50.

Jeeves was poised to be the internet’s first breakout character. He appeared in a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade float, reportedly the first web-based personality ever to do so. The site signed with high-profile Hollywood agent Michael Ovitz and plotted an aggressive merchandising campaign that would see toys, apparel, and other product further familiarize Jeeves to the public.

(None of this was lost on the Wodehouse estate, which questioned whether Ask Jeeves had infringed on their rights to the Jeeves character. While they owned the butler, the Jeeves of the web was not quite the Jeeves of the books, and both parties announced a non-disclosed settlement in 2000.)

Jeeves would finally lose his composure in 2001, when the dot-com bubble burst. Advertisers fleeing from web development led to mass casualties online. The company posted a $425 million loss in 2001; shares plummeted to 86 cents in 2002. Despite his sharp appearance, Jeeves was dangerously close to insolvency.

Ask Jeeves Minus Jeeves

Ask Jeeves would rebound from those dark times. The site was reconfigured to be more search-oriented with the addition of a third-party engine, and Jeeves was recast as more of a mascot; a 2003 ad campaign didn’t even feature him. That same year, Gruener was able to post the company’s first-ever profit, thanks in large part to an ad revenue deal with Google. But the behemoth in the search engine space wasn't sharing the market: It owned 32 percent of the industry compared to just 3 percent for Ask Jeeves.

In 2005, Barry Diller’s InterActive Corp. (IAC) purchased the site for $1.85 billion with an eye toward making it less about questions and more about general searches. Gruener departed; Ask Jeeves morphed into Ask.com, and the butler disappeared entirely the following year.

Why? Perceiving Jeeves to be representative of the 1990s internet culture, Diller and IAC believed his charm had run its course. “I don't see many tears on the floor," Diller said of the character’s absence.

While Diller had designs on being competitive with Google, it was not to be: That site went on to claim a clear dominance of the search market. By 2010, corporate support for Ask.com had dwindled, although the URL remains a part of the search engine landscape. Aside from a brief return in 2009 in the UK, Jeeves has been unavailable to field any additional questions.

A version of this story ran in 2017; it has been updated for 2023.