Anthony Comstock wanted to show Congress his sex toys.

In the spring of 1872, Comstock—a New York City resident who had parlayed a puritanical upbringing into a one-man crusade against vice—headed to Washington to stir up support for legislation that would make sending pornographic materials through the mail a federal offense. But it wasn’t just explicit content Comstock was looking to curb: He wanted a blanket ban on contraception and sex toys, the latter he dubbed “articles made of rubber for immoral purposes.” He toted several examples of each for politicians to inspect as evidence the country was awash in sinful temptations.

Comstock soon got his wish, along with an appointment as an official postal inspector. He would spend virtually the next half-century stifling sexual education and expression in American culture. The end goal was to guarantee what one newspaper dubbed the “sanctity and purity of the home” by discouraging promiscuity and hedonism. The American way of life was seemingly up to Comstock and his weaponized virtue to preserve by any means necessary.

In his career resisting moral turpitude, Comstock was shot at, knifed, and satirized; he was vilified by both free speech proponents and the smut merchants he routed into prison. But the majority celebrated his war on lascivious behavior.

Whether one supported or resisted his pursuit, one thing had become clear. As one newspaper noted in 1895, “There is hardly a person in America who has not heard of Anthony Comstock.”

A Puritanical Mind

Comstock was born March 7, 1844, in the bucolic town of New Canaan, Connecticut. His father, Thomas, owned a farm and two sawmills; his mother, Polly Ann, kept their 10 children immersed in a congregationalist curriculum that promoted good moral hygiene. Faith was arguably a much-needed commodity at a time when illness could rapidly thin families. Of Comstock’s nine siblings, just six survived into adolescence; Polly died when he was 10 years old, but her influence would remain with him forever.

“Purity, principle, duty,” summarized Comstock biographer Charles Trumbell, “were watchwords often on his mother’s lips.”

Temperance and responsibility seemed to go hand-in-hand for Comstock. As a youth, he sprang into action when a local complained of a rabid dog on the loose, killing the animal before it could go on the attack. As a teen, he snuck into a saloon and drained it of its alcohol—an early sign Comstock would force his strict moral fabric on others.

In 1863, the family lost his older brother, Samuel, in the Civil War. Comstock enlisted in his place and was dispatched to a largely bloodless tour in Florida as part of the Union Army. His intolerance of drinking and profanity did not endear him to his fellow servicemen, who were predictably annoyed at being scolded for their vices.

After the war, Comstock moved to New York City, a common decision for young men seeking employment. He found it at a dry goods store, where he began working as a clerk in 1867. But he also found the city to be brimming with the very type of immorality he despised. Pornography was available in the darker corners of bookstores; bars, prostitution, gambling, and other vices were plentiful. To Comstock, New York was a spiritual vacuum.

The extent of Comstock’s intolerance extended to live entertainment. “Why, it was awful, awful,” he recalled of one show he viewed while visiting Chicago’s eclectic Midway hotspot during the World's Fair. “Never did I see such sights … it is the most outrageous insult to womanhood, the most shameless exhibition of depravity, the worst violation of all decency, and virtue and respectability and innocence that I have ever heard of.” Comstock was referring to a woman dancing suggestively.

His fears of sex being a corruptive influence were confirmed when a co-worker made an admission: He had bought some explicit photos from a local shop and feared they had poisoned his soul, enticing him into visiting a sex worker. Enraged, Comstock visited the shopkeeper, Charles Conroy, and pretended to be another customer with prurient interests. When Conroy sold him a smutty paperback, Comstock raced to find police. Conroy was hauled off for the illegal sale of pornography. He was Comstock’s first bust, and he wouldn’t be the last. Comstock had found his calling.

At first, Comstock used his own modest salary to fund his vigilantism, buying illicit material and then turning proprietors over to authorities. He was soon backed by the Young Men’s Christian Association, better known as the YMCA, which was in lockstep with Comstock’s moral ambitions. They paid his bills in the belief that he was actively cleaning up the city’s streets and reducing temptations.

Businesses did not appreciate the disruption. Comstock, who carried a gun, was accustomed to violence. One disgruntled shopkeeper attacked him with a knife, severing nerves in his face. An explosive device was sent to him but failed to go off; he opened another box to find rags he later learned had been contaminated with smallpox in the hopes he would be infected. One would-be assailant followed him through the streets—and when cornered by police, he was found to have a weapon that likely would have fatally wounded the unsuspecting Comstock.

Rather than be discouraged, Comstock was emboldened. And his ambitions went beyond New York.

A Federal Case

An 1865 law prohibited pornographic or obscene material being sent through the United States mail. But Comstock believed the law could be broader. Among the items he found disagreeable were birth control instructions, early forms of contraceptives like sponges and spermicidal products, abortion literature, and sex toys—all of which Comstock believed contributed to a casual attitude toward sex, an activity he believed should be reserved only for marriage. (He and wife Margaret, whom he married in 1871, were unable to have children.)

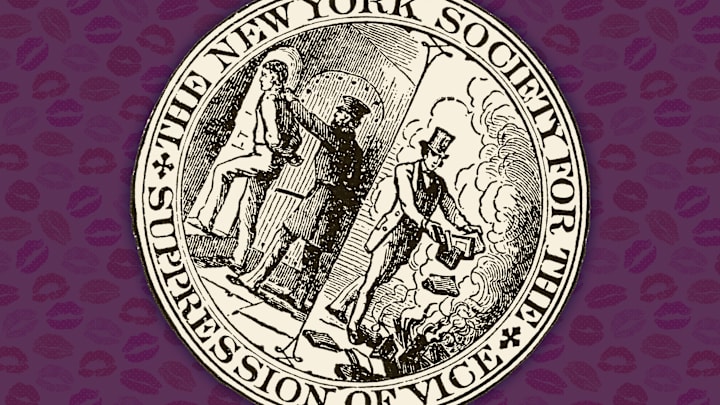

In 1872, Comstock achieved two significant goals. Under the auspices of the YMCA, he chaired the Society for the Suppression of Vice, an organization devoted to the abolition of such material. He also made a successful trip to Washington, sex toys in tow, to petition Congress to introduce a federal anti-obscenity act that would make the mail-order distribution of his banned items illegal. This was a surefire method for extending his agenda across state lines and bypassing any jurisdictional issues.

There was some opposition in Congress, but not much: The act was introduced and passed, with then-president Ulysses S. Grant signing it into law in 1873. Due to his influence, it was known as the Comstock Act.

Its purpose was best summarized in an 1876 amendment: “Every obscene, lewd, or lascivious book, pamphlet, picture, paper, writing, print or other publication of an indecent character, and every article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception or procuring of abortion, and every article or thing intended or adapted for any indecent or immoral use, and every written or printed card, circular, book, pamphlet, advertisement, or notice of any kind giving information, directly or indirectly, where, or how, or of whom, or by what means, any of the hereinbefore mentioned matters, articles, or things may be obtained or made, and every letter upon the envelope of which, or postal card upon which, indecent, lewd, obscene, or lascivious delineations, epithets, terms, or language may be written or printed, are hereby declared to be non-mailable matter, and shall not be conveyed in the mails, nor delivered from any post-office, nor by any letter-carrier.”

With the law came a new title: Special agent of the U.S. Post Office. Comstock now had federal powers to back his crusade, and he made liberal use of them. He often posed as a customer, requesting lewd materials to be sent to mailing addresses he had set up around the country. When an offender complied, he used the transaction as evidence. Police conducted raids at his behest, seizing printing plates, books, photos, and immoral rubber of all kinds. Consequences were severe: Convicted offenders could be fined thousands of dollars and jailed for up to 10 years.

Comstock made no accommodations for the consequences of his crusade: He once boasted that 15 defendants had died by suicide, too demoralized by the potential for prison or fines to go on. Older or infirm women who had assisted or otherwise informed about birth control or abortion were shown no mercy.

As is often the case with censorship, the line between exploitative and artistic was not one Comstock was willing to assess. Caught up in his zealous crackdown was a catalog intended for students of an art college owing to illustrations of nude figures within. (The charges were dropped but the catalogs were destroyed.) Later in his career, he targeted a painting titled September Morn by artist Paul Chabas featuring a nude woman wading into water. An art gallery had put a print of it on prominent display in New York; Comstock was aghast. Following a tip, he marched to the gallery and demanded it be removed.

“But that is the famous September Morn,” the salesman said.

“There’s too little morning and too much maid.” Comstock responded. “Take it out.”

Comstock’s ire was not reserved solely for sex. He also had a disdain for quack therapies, medical “cures” that purported to heal while being little more than placebos. Such concoctions were also illegal to mail, as were illicit lottery games and phony land deeds. In this way Comstock was something of a consumer advocate, though once again he had no capacity for nuance. A raffle held to help Belgian immigrants was canceled upon receiving a Comstock threat; other “lottos” organized by churches for charity were likewise shut down. Even in a modest society, Comstock assailing priests was a step too far, and he received his share of backlash.

There were attempts to discredit him. In 1894, a man up on charges of “disorderly housing” accused Comstock of floating the idea of a bribe. For $1000, Comstock allegedly told the man he could make his legal problems disappear. Comstock vehemently denied the charge, declaring it “perjury.” With no proof offered, the man’s claim fell by the wayside.

Comstock kept up his fight through 1915. While in the process of guiding a prosecution of William Sanger, husband of contraception proponent Margaret Sanger, for distributing her birth control pamphlet Family Limitation, Comstock was struck by pneumonia and what The New York Times described as “overwork and over-excitement.” He died September 21, 1915, after causing no fewer than 2740 people to plead guilty or be convicted of selling or distributing prohibited materials, totaling roughly $231,000 in fines and 566 years in prison.

The so-called Comstock Act was defanged over time, though it took a while. Laws against contraceptives persisted through the 1960s. Even now, any attempt at strict censorship carries a colloquial term: Comstockery.

Read More History: