When people think of destructive floods, they tend to think of water. But there are some rarer cases of other liquid substances causing utter catastrophes. While a mass of melted chocolate rushing toward you might sound like a dream in theory, in practice, floods of all kinds have the potential to bring death and destruction. Here are some of the most disastrous non-water floods throughout history—ranging from waves of food and drink to toxic waste spills.

- The London Beer Flood

- The Dublin Whiskey Fire

- The Great Molasses Flood

- The Rockwood Chocolate Flood

- The Aberfan Disaster

- The Church Rock Uranium Mill Spill

- The Wisconsin Butter Flood

- The Kingston Fossil Plant Spill

- The Ajka Red Mud Spill

- The Mariana Dam Disaster

The London Beer Flood

At the start of the 19th century, Meux and Company’s Horse Shoe Brewery in London was home to a massive 22-foot high fermentation vat that could hold the equivalent of around 3500 barrels of beer (in this case, it was brewing porter ale). On October 17, 1814, one of the tank’s iron support rings snapped and the hot fermenting liquid blasted out with such force that it not only burst open a few surrounding vats—amounting to around 320,000 gallons of beer being set free—but also crashed through the wall of the brewery.

The 15-foot-high wave of hot beer flooded the crowded slum of St. Giles Rookery, destroying a few buildings and killing eight people—five of whom were mourners at the wake of a 2-year-old boy. According to The Morning Post, “the surrounding scene of desolation presents a most awful and terrific appearance, equal to that which fire or earthquake may be supposed to occasion.”

There were later rumors that at least one further person died of alcohol poisoning after drinking too much of the free ale. But no contemporary newspapers reported such an occurrence, making the drunken death tale doubtful.

The Dublin Whiskey Fire

While it’s unlikely that anyone died from drinking too much during the London Beer Flood, alcohol poisoning was the sole cause of death during the Dublin Whiskey Fire. On the evening of June 18, 1875, a fire at Malone’s bonded warehouse in central Dublin burst open 5000 wooden casks containing whiskey and other spirits. The alcohol flowed out of the building in a shallow river, estimated to be 2 feet wide and 6 inches deep.

While firefighters tackled the blaze, many Dubliners flocked to the whiskey river to drink their fill. “It is stated that caps, porringers, and other vessels were in great requisition to scoop up the liquor as it flowed from the burning premises, and disgusting as it may seem, some fellows were observed to take off their boots and use them as drinking cups,” The Irish Times reported. A total of 13 deaths are attributed to the incident—all due to alcohol poisoning—and multiple rows of tenement buildings were destroyed.

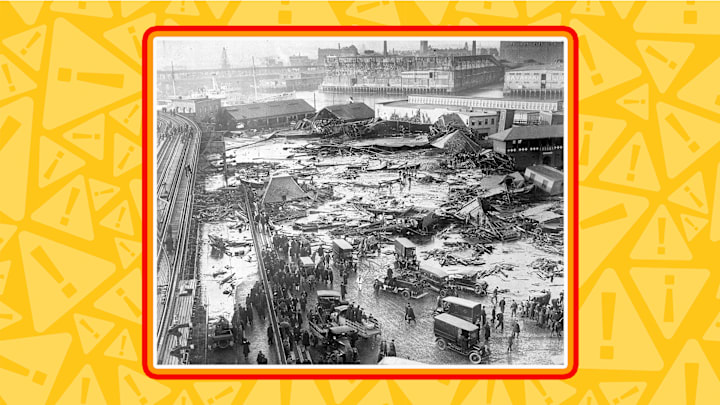

The Great Molasses Flood

Anyone who has baked or cooked with molasses knows just how sticky a substance it is. But Bostonians know this better than anyone due to the Great Molasses Flood that hit the city’s North End neighborhood at the start of 1919.

In 1915, the Purity Distilling Company cut every corner they could when constructing an enormous tank to hold molasses. The 50-foot-tall and 90-foot-wide tank was made of a steel blend that was too brittle for its purpose, half as thick as it needed to be, and its rivets weren’t properly reinforced. The tank started leaking immediately—but the company simply had the tank painted brown so the escaping molasses would be less noticeable.

Something eventually had to give. The tank burst open on January 15, 1919, causing around 26 million pounds of molasses to tear through the city in a 15-foot high wave that moved at 35 mph. The dense substance demolished buildings and brought down an elevated train track. Several city blocks were submerged in two to three feet of molasses and 21 people were killed, with a further 150 injured.

The syrupy goo also posed a problem long after the initial wave. It took more than 80,000 hours of work to clean up and everyone who came into contact with the sticky mess—from rescuers and cleaners to survivors and rubberneckers—inadvertently spread molasses around Boston. For decades afterwards, locals said that the city still sometimes smelled of molasses.

The Rockwood Chocolate Flood

A few months after Boston was hit by the molasses wave, Brooklyn was covered in molten chocolate. On May 12, 1919, a fire tore through chocolatier Rockwood & Company’s Brooklyn storehouse, causing a mixture of cocoa, butter, and sugar to melt and ooze out onto the street. The thick mixture blocked the storm drains; Hugh Ward from the Street Cleaning Department said the resulting flood “was deep enough to float a rowboat for two blocks along Flushing Avenue.”

As would be expected, word of the chocolate river traveled fast and children flocked to the sweet site to drink their fill. “Little fellows fell on their knees before the oncoming flood and dipped it up greedily with their grimy fingers,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported. No one suffered death by chocolate, but one firefighter was injured while tackling the blaze and around $75,000 (almost $1.4 million today) of damage was done to the storehouse.

The Aberfan Disaster

From 1916, the mountainside above the small Welsh mining town of Aberfan was home to a growing number of colliery spoil tips. On the morning of October 21, 1966, one of the tips—containing 2.1 million cubic meters of coal waste—avalanched down the mountain, destroying everything in its path, which included a number of houses, as well as Pantglas Junior School and part of County Secondary School. A total of 144 people were killed by the black slurry, 116 of whom were children.

Survivor Brian Williams, who was 7 at the time, later recalled sitting in his classroom and hearing a loud noise approaching. “The best way I could describe it later on—because I’d never heard anything like that at the time—was like when you go to an airport and you hear an aeroplane coming in to land,” he said. The next thing he knew, the classroom wall had come down and sludgy waste filled the room. Much of the rest of the school was totally demolished.

Although the National Coal Board tried to blame heavy rain for the disaster, their own unsafe practices were identified as the culprit and legislation was passed to tighten the rules on tipping.

The Church Rock Uranium Mill Spill

The grim title of largest radioactive spill in U.S. history goes to the Church Rock uranium mill spill of 1979. The dam of the uranium mill burst on July 16 of that year, unleashing 1100 tons of tailings and 94 million gallons of toxic waste into the Puerco River and onto the land of the Navajo Nation. Although the nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island—which occurred just four months earlier—attracted far more attention, the Church Rock incident released three times as much radiation.

Not only did the United Nuclear Corporation know that there were cracks in the dam at least two years before the breach occurred, but residents weren’t properly warned of the danger and very little was done to clean up the mess afterwards. People who touched the contaminated water suffered burns, plants along the river withered, and animals died.

Livestock still showed the effects of radiation poisoning years after the disaster. Larry King, an underground surveyor who reported cracks in the dam (to no result), explained that “sheep were born hairless … like baby rats” and their stomach fat—which should have been white—was bright yellow.

The Wisconsin Butter Flood

On May 3, 1991, a fire broke out at Central Storage & Warehouse in Madison, Wisconsin. Within a few hours, the contents of the warehouse—including 20 million pounds of butter—liquefied and flowed out of the building in a greasy river. Firefighters had to wade through two to three feet of melted butter and cheese to tackle the blaze. “I had butter in places a guy shouldn’t have butter by the end of that night,” Fire Department Chief Steven Davis said.

The butter river was in danger of flowing into Lake Monona and the dams that had been constructed to channel the flow into the sewage system weren’t keeping up, so the mixture had to be pumped. By May 6, around 14 million gallons of liquid had been pumped into the sewers. The fire itself took eight days to put out and the total estimated damage came in at $70 million in warehouse contents, $7.5 million in property damages, and almost $1 million for clean-up.

The Kingston Fossil Plant Spill

The Kingston Fossil Plant Spill is the largest industrial spill in U.S. history, with more than a billion gallons of coal ash spilling out of a dike at the Tennessee plant on December 22, 2008. The flood of toxic sludge—which contained cancer-causing toxins such as lead, arsenic, and uranium—destroyed around two dozen houses before flowing into the Emory River. Although no one died during the initial spill, the clean-up crew started to get sick and die in the following years.

“We were told constantly throughout the years that [coal ash] was safe. That you can eat it and drink it and it won’t hurt you,” clean-up worker Michael McCarthy explained. Not only did McCarthy himself develop heart and lung problems because of breathing in the toxic materials, but his family—who were exposed via his work clothes—also developed ash-related illnesses. Ten years after the incident, around 250 of the 900 clean-up workers were sick and more than 30 of them were dead from exposure to the ash.

Many of the workers filed a lawsuit against Jacobs Engineering for failing to provide adequate safety equipment and a monetary settlement (of an undisclosed amount) was finally reached in 2023.

The Ajka Red Mud Spill

Refining bauxite into usable alumina causes a red mud that is highly alkaline to be leftover as a waste product. On October 4, 2010, the mud reservoir at Ajka alumina plant in Hungary collapsed and released a 700,000 cubic meter wave of the toxic material. Buildings in the nearby towns of Kolontár and Devecser were flooded; the mudslide reached as far as the Danube River. Around 200 people suffered chemical burns and a further 10 people died. In 2019, 10 members of staff at the aluminum plant were convicted of criminal negligence.

The Mariana Dam Disaster

On November 5, 2015, the dam holding back the tailings from the Germano iron ore mine in Brazil collapsed, sending 50 million cubic meters of toxic mud out into the Rio Doce Basin. The nearby village of Bento Rodrigues was hit the worst, but the mudslide swept through many communities on its 16-day journey to the Atlantic Ocean. Hundreds of buildings were swept away or buried in mud and 19 people were killed.

The mud also contaminated the Doce River, killing wildlife and disrupting the lives and livelihoods of nearly a million people. The incident has gone down in history as Brazil’s worst environmental disaster. The owners of the dam, BHP and Vale, set up the Renova Foundation to compensate victims of the disaster, but they also spent years wading through lawsuits, with a staggering 620,000 people taking BHP to court and 70,000 suing Vale.

Read About More Disasters: