Imagine it’s the future, and you happen upon a vinyl record. For the purposes of this thought experiment, let’s pretend you know it harbors audio—but not only are there no longer record players in existence, nobody even remembers what one looks like or how it would work. In short, if you want to hear what’s on the record, you’ll have to come up with a whole new method of playing it.

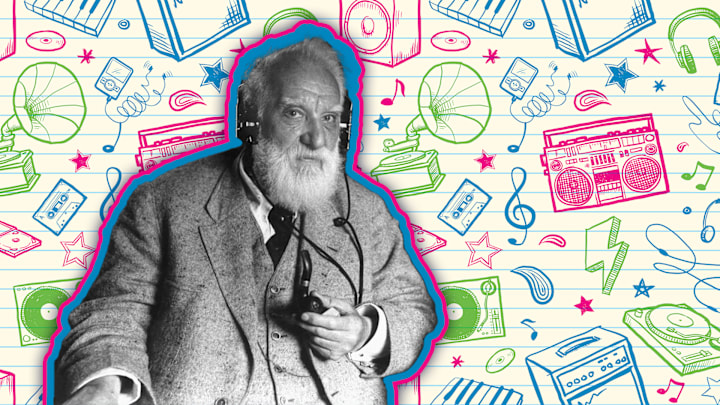

For years, that was pretty much how things stood with Alexander Graham Bell’s early audio recordings.

The Medium Without the Message

In 1880, France gave Bell a cash prize for his telephone invention, and he used that money to establish the Volta Laboratory in Washington, D.C. There, Bell and his colleagues—including his cousin Chichester Bell and fellow inventor Charles Sumner Tainter—spent a large portion of time between 1880 and 1886 trying to figure out the best way to record sound.

As Bell biographer Charlotte Gray wrote for Smithsonian back in 2013, they’d scratch the soundwaves into discs or cylinders made with various materials: everything from metal, glass, and wax, to foil, cardboard, and even plain old paper.

The discs and cylinders themselves survived; Bell donated a good 400 of them to the Smithsonian Institution. Unfortunately, whatever playback techniques he and his cohort employed are still a mystery. So while contemporary researchers—like the hypothetical future you from the introduction—knew they had sound on their hands, they couldn’t make it heard.

Come On, IRENE

A promising development in the field of audio recovery occurred about 20 years ago, when physicist Carl Haber and others at California’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory came up with a contactless system to restore old and fragile records without damaging them. Basically, they take extremely detailed scans of the grooves to create a digital map of the recording, and then apply software that can track the path of a stylus (like the needle of a record player) through that map. They named the technology IRENE (Image, Reconstruct, Erase, Noise, Etc.) after their first test case: a 1950 recording of the Weavers’s “Goodnight Irene.”

In 2011, Haber and company began collaborating with the Smithsonian National Museum of American History (NMAH) and the Library of Congress to decipher some of Bell’s enigmatic artifacts. Since then, IRENE has successfully recreated the audio from 20 of them, including a Hamlet speech, “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” a bunch of numbers, and—perhaps most exciting—Bell’s own voice.

So what’s on all the other discs and cylinders? Hopefully, we’ll soon find out. This fall, as Smithsonian reports, the NMAH is launching a three-year-long endeavor to restore the rest of the Volta Laboratory’s extant recordings—roughly 300 or so. The project, titled “Hearing History: Recovering Sound from Alexander Graham Bell’s Experimental Records,” is being funded by a grant from the National Park Service’s Save America’s Treasures program, as well as contributions from the Alexander and Mabel Bell Legacy Foundation; Curb Records founder Mike Curb and his wife Linda; and fashion software company SEDDI, Inc.

[h/t Smithsonian]