The image of writers as always true to their own spirits and invulnerable to the words of critics is a powerful one—yet the history of literature shows that sometimes, even the greatest authors aren’t completely immune to outward criticism ... or the impulse to keep polishing. Here are five authors who rewrote previously published books, either because they received critical responses, their views changed, or because they were restoring their original vision.

1. Mary Shelley // Frankenstein

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus—first published when she was only 20 years old—has become one of the most famous works of supernatural fiction. What is less well-known, however, is that the book was changed in a number of ways between that original publication, published anonymously in 1818, and a revised edition written by Shelley in 1831.

Part of the reason for the changes was contractual: The publisher of the 1831 edition had made a business of buying books near the end of their copyrights, having the author write new material if possible, and then attempting to extend the copyright protections.

But modern scholars tend to agree that what played a bigger role in the changes was personal tragedy. According to UCLA Professor Anne K. Mellor, between 1818 and 1831, two of Shelley’s children, as well as her husband Percy, had died, and some of her closest friends had turned their backs on her—all of which, Mellor writes, “convinced Mary Shelley that human events are decided not by personal choice or free will but by an indifferent destiny or fate.” The result is that while in the 1818 edition Victor Frankenstein chooses to make the creature out of a sense of hubris and his own free will, in the 1831 edition, he’s at the whim of forces outside of his control [PDF].

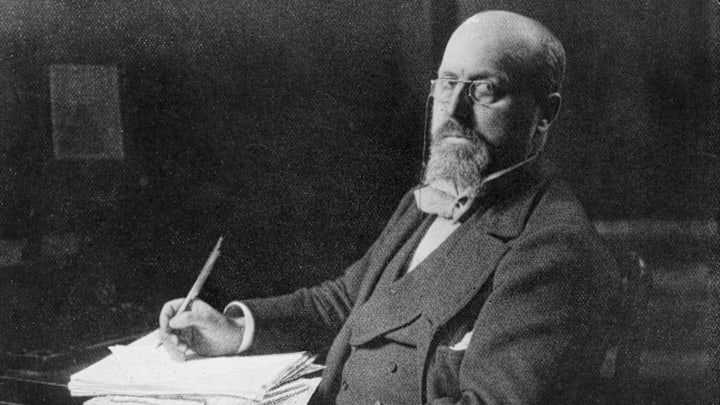

2. George Eliot // Middlemarch

The conclusion of George Eliot’s Middlemarch (1871) is one of her most famous pieces of writing, including the eloquent description of her central character Dorothea (“Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth”), and the last lines, which inspired the title of Terrence Malick’s film A Hidden Life (“[F]or the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs”). But the version people are familiar with today isn’t the original: The first version of Middlemarch’s ending was significantly longer and contained a number of details not found in the text we read today. So why did Eliot edit the ending after its original publication?

The influential critic Richard Holt Hutton wrote in mostly laudable terms about Middlemarch when the final installment was published, but he criticized aspects of the ending—especially a comment that the community in the novel had “smiled on” a marriage between an elderly man and a young woman, when earlier sections of the book had actually described their disapproval of the union.

“[T]he remark as to the world's ‘smiling on a proposition’ of marriage from a sickly man to a girl less than half his own age, really has no foundation at all in the tale itself,” the critic wrote [PDF]. “When Mr. Brooke, Dorothea's uncle, weakly carries Mr. Casaubon's offer to Dorothea, he accompanies it with as much slipshod dissuasion as it is possible for so helpless a nature to use. Dorothea’s sister Celia hears of it with an ill-disguised horror of disgust, which bitterly offends Dorothea. If the rector’s wife, Mrs. Cadwallader, represents county opinion (and who could represent it better?), the whole society disapproved it.”

Hutton had written highly of Eliot’s earlier novel Romola—a fact that pleased her greatly [PDF]—and her respect for his opinion likely influenced her decision to rewrite Middlemarch’s ending to remove these inconsistencies, which had also been noted by others.

3. Henry James // The Portrait of a Lady

Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady (first published in book form in 1881), chronicles the story of idealistic Isabel Archer, her disastrous marriage, and the other men who love her, including kind-hearted Caspar Goodwood. It concludes on a seemingly ambiguous note, when Caspar comes to visit Isabel only to be told by her friend Henrietta that she has already left to travel overseas, ending with the following exchange between Henrietta and Caspar: “‘Look here, Mr. Goodwood,’ she said; ‘just you wait!’ On which he looked up at her.”

The meaning of this is arguably open to interpretation, but Richard Holt Hutton, writing in The Spectator, believed James was clearly hinting that Isabel will eventually leave her husband for Caspar: He just has to “wait,” as Henrietta has promised. At the time, many considered it scandalous a woman to leave her husband (no matter how horribly the husband had treated her), and Hutton was outraged about what he believed to be the ending’s meaning.

James was known to have read Hutton’s reviews, and when he eventually revised the novel in 1906, he made a large number of changes to the text. One of the most striking alterations is that the ending was changed to clarify that there was no prospect of Isabel uniting with Caspar, and Henrietta’s words are only to reassure him that he will eventually move on. The final ending reads: “On which he looked up at her—but only to guess, from her face, with a revulsion, that she simply meant he was young. She stood shining at him with that cheap comfort, and it added, on the spot, thirty years to his life. She walked him away with her, however, as if she had given him now the key to patience.”

4. Evelyn Waugh // Brideshead Revisited

Brideshead Revisited is arguably the novel for which Evelyn Waugh is best known, yet the first edition, published in 1945, was different in certain respects from today’s version. Initially, Waugh had been pleased with much of the critical response, and dismissive of those who disliked it, declaring that “Most of the reviews have been adulatory except where they were embittered by class resentment.”

However, Waugh’s doubts gradually surfaced, and he later wrote to a friend that “all that those nasty critics said was bang right” and vowed to revise the novel, which he did in 1959. He altered the structure from two books to three and changed some notable lines, among them his original description of Oxford as having “the soft vapours of a thousand years of learning,” which was replaced in the revised version with “the soft airs of centuries of youth.” In addition, this version toned down some of the original’s nostalgia, partly because the way of life that Waugh believed in 1945 to be coming to an end (such as the maintenance of grand country estates in England), had remained surprisingly resilient by the late 1950s.

5. Joan Lindsay // Picnic at Hanging Rock

Joan Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (first published in 1967) tells the story of a group of students and their teacher who disappear while visiting a rock formation in Victoria, Australia, on Valentine’s Day in 1900. All but one of the victims are never found, and the mystery of their disappearance is never solved.

But the original version of the novel was different. Lindsay had initially written an extra chapter that stated the reason for the women’s disappearance: a mystical event caused a hole in the rock to open; three of the girls walked inside, after which the crack in the rock closed again. When Lindsay took the book to editors for consideration, one suggested the novel would actually be improved by leaving out this explanation. Lindsay agreed, and the book was published without it.

However, Lindsay herself always longed to reveal the solution, and eventually entrusted her agent with the manuscript of the missing chapter, asking that it to be made available after her death. In 1987, the final chapter, originally intended to be chapter 18 in the original novel, was published as a standalone work titled The Secret of Hanging Rock. But critical opinion was divided on the merits of explaining the mystery, and the additional chapter was never reintegrated back into the story as a whole. The most widely read version of the novel today remains the version that omits chapter 18 and leaves the story unresolved.