It was supposed to be an urban oasis in the middle of the Canadian wilderness.

Kitsault, built in the remote reaches of British Columbia during the late 1970s and early ‘80s, boasted all the coveted attractions of a small city or town: a shopping mall, a gym, a theater, banks, restaurants, schools, a pub and—in true Canadian fashion—a curling rink. After construction was completed in 1980, more than 1200 people moved to Kitsault, hoping to build prosperous futures around a recently revitalized mine. But just 18 months later, the mine was closed. By 1983, Kitsault had been completely abandoned.

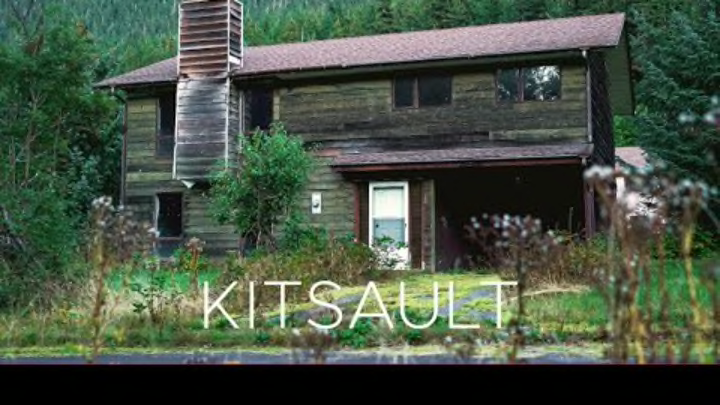

This chapter of Kitsault’s history does not make it particularly unusual, as far as ghost towns go. Over the centuries, many once-populated communities have been deserted when the economic activity that supported them ceased to flourish. But unlike other ghost towns, Kitsault was not left to wither and crumble. Instead, it has been carefully maintained over the years, surviving today as a pristine time capsule of a bygone era.

The rise and fall of Kitsault is tied to a metal called molybdenum, which is used in steel production. When its value began to climb in the late 1970s, a company called Amax Canada Development decided to reopen an existing molybdenum mine [PDF] some 550 miles north of Vancouver. But there was a problem. The mine was located in a lightly populated area of the province, far from any major city and inaccessible by road. Workers had previously commuted to the mine by boat from a small town nearby, but the new operation would require hundreds of employees. How could people be enticed to move there?

Amax decided to build a modern, self-sustaining town in the wilds of British Columbia—a place where workers would want to settle with their families. Apartments and detached homes curved around “winding roads and cute street lights,” writes journalist Justin McElroy. There was plenty to do for entertainment—be it a game of curling or a dip in the recreation center’s Jacuzzi. Kitsault even had a modern hospital for its residents’ medical needs.

But almost as soon as Kitsault came to life, the price of molybdenum crashed. The mine closed in late 1982, and soon after, Kitsault’s residents were ordered to leave the town. Because the decline happened so quickly, and because Kitsault was so hard to reach, much of the infrastructure and many objects were simply left behind. Today, there are still books in Kitsault’s library and toys in its daycare. Rows of grocery carts remain in the supermarket, and medical supplies linger in the hospital.

For a time, hoping that it would be able to resurrect the mine and the town, Amax employed caretakers to maintain Kitsault. In 2005, Krishnan Suthanthiran, a medical product entrepreneur, purchased the entire town for under $7 million. He launched a restoration project, upgrading Kitsault’s water systems and renovating its buildings, and continues to employ multiple caretakers to look after it. Over the years, Suthanthiran has floated various plans for Kitsault—among them transforming the ghost town into a hub for scientists and artists, or converting it into a natural gas terminal. But so far, none of those plans has materialized.

The few tour groups who are allowed to visit every year can bask in the nostalgia of Kitsault’s retro aesthetic (think burgundy carpets and geometric tiling) and experience its eerie desolation. But for the most part, the town remains closed to the public—the relic of a community’s dreams and aspirations, frozen in time.