Some inventions are so ubiquitous these days that it’s hard to imagine life without them—like phones, light bulbs, and indoor plumbing. Others changed the world behind the scenes, revolutionizing an industry before getting outpaced by more advanced technology. The spinning jenny is one of the latter.

Long before workers known as Luddites began destroying machinery that could replace them amid England’s Industrial Revolution, the invention of the spinning jenny also prompted innovation, fear, and cases of corporate sabotage.

Who Invented the Spinning Jenny—and Why?

Before the Industrial Revolution, European textile manufacturing was a cottage industry: Workers completed disparate parts of the process, which was sometimes a family affair, mostly within their own homes. Children would use special brushes to comb out or “card” wads of cotton (or another raw material, like wool), which were then rolled into long, thin pieces. After that, the mother would fasten the cotton to a spindle attached to a spinning wheel; and as she manually rotated the wheel, the spindle would spin, twisting the cotton into a tighter and tighter spiral until it was thin, strong yarn. The father was then responsible for weaving yarn into cloth using a loom.

That’s not to say the division of labor always followed that exact system. But in general, the process was very manual and very slow-going, with many steps requiring actual skill. It was only a matter of time before people started inventing machines that could make things more efficient—which is what the spinning jenny did for the workers who turned carded fibers into yarn.

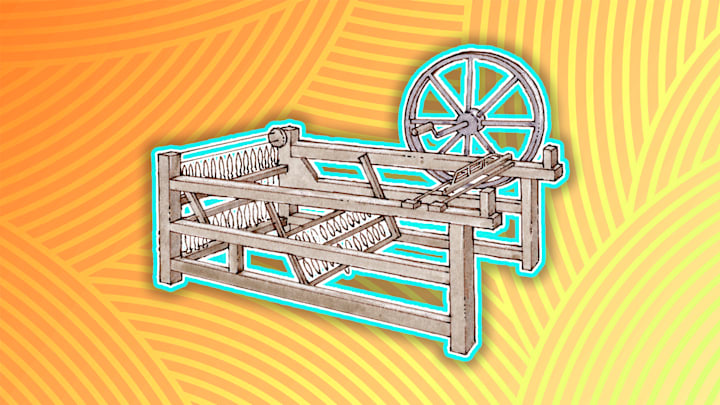

The spinning jenny was invented by a weaver named James Hargreaves, of Lancashire, England, circa 1764. His original model was a frame with eight vertical spindles in a row and two horizontal wooden bars that held the other ends of the rovings—the lengths of cotton—in place between them. The operator moved the wooden bars to pull the rovings to the proper tautness with one hand, and cranked the spinning wheel with the other hand.

Not only could you spin yarn eight times faster with the spinning jenny, but you also didn’t need much skill to use it properly. With a regular spinning wheel, you had to hold one end of the roving and carefully draw it farther from the spindle as you spun the wheel. The spinning jenny helped mechanize that part of the process.

Initially, Hargreaves just used the spinning jenny in his own household and tried to keep it under wraps. But word soon spread of the innovation, and local spinners—fearing they’d soon be out of work if the jenny caught on—descended on the Hargreaves’s home and demolished the jenny. Its inventor became such a persona non grata that he moved his family to Nottingham in 1768.

There, he and a business partner named Thomas James founded a mill and started using the spinning jenny to supply yarn to hosiers. After Hargreaves was granted a patent for his invention in 1770, he tried to sue other manufacturers who’d begun using spinning jennies in their own businesses, but the case fell apart once it came to light that Hargreaves had sold several jennies before receiving a patent. In other words, the technology had already been freely available to copy for a while, and Hargreaves couldn’t retroactively request payment from people who’d taken advantage of that freedom.

By the time Hargreaves died in 1778, people had modified the machine to hold way more than eight spindles. (Even Hargreaves hadn’t stopped at eight: The version in his patent application had 16.) Hand-spinners considered this a serious threat to their livelihood, and in 1779 a mob of Lancashire spinners systematically destroyed a number of jennies in the area.

But the Industrial Revolution was a force that couldn’t be stopped, and the textile industry wasn’t about to return to its cottage days if yarn could be spun in factories with cheap (often child) labor. Spinning jennies may have already numbered in the tens of thousands across Britain by the end of the 1770s. The invention’s fame, however, would be short-lived—because a shiny new model had just arrived on the scene.

Spinning Jenny vs. Spinning Mule: What’s the Difference?

The spinning jenny had its shortcomings. For one thing, it was far from fully automatic: You still had to spin the wheel and move the wooden bars to pull the rovings taut. For another, it didn’t produce yarn durable enough to serve as warp—the long yarn woven vertically through the weft, which is shorter, weaker yarn that runs horizontally through fabric. The spinning jenny could only make weft.

Throughout the 1760s and 1770s, other people tinkered to perfect the process of mechanized cotton-spinning; and in 1779, Samuel Crompton, also from Lancashire, unveiled a machine that would supersede the jenny in factory use: the spinning mule. It was an offshoot of the jenny that borrowed facets of another contemporary invention, Richard Arkwright’s water frame, which spun much stronger thread by first passing the rovings between two stacked rollers. The spinning mule is widely believed to have gotten its name because it’s a hybrid of the jenny and the water frame, much like a mule is a hybrid of a horse and a donkey.

Crompton’s original mule featured 48 spindles, but that number eventually increased to more than 1000 as manufacturers sized up the machines in spinning mills. While workers still oversaw production, they didn’t have to manually operate the mule: Water power did it for them (and then steam engines, and, later, electricity).

Unfortunately, Crompton didn’t patent his invention, instead sharing its design with local manufacturers in return for money. He only ended up making £60, though in 1812 Parliament did award him £5000 as thanks for his contribution to industrialization. It was a pretty paltry sum, considering that by then there were some 360 mills operating 4.6 million mules spindles across the UK.

Why Is It Called the “Spinning Jenny”?

One popular legend states that Hargreaves was inspired to create the spinning jenny after his daughter Jenny knocked over a spinning wheel and he realized the spindle could still function vertically; so he named it after her. Another theory posits that he named it after his wife. According to records, though, Hargreaves was married to a woman named Elizabeth; and of their 12 children, none was named Jenny. In short, there’s a good chance both stories are apocryphal.

It’s also been suggested that it was actually named after the daughter of Thomas Highs, who had created his own iteration of a spinning jenny around the same time. Yet another hypothesis is that Hargreaves was using jenny as slang for engine. For what it’s worth, the Oxford English Dictionary simply says that “the reason for this use of the personal name [Jenny] is uncertain.”