On January 22, 1892, Norwegian artist Edvard Munch wrote a fateful entry in his diary. He was in Nice, France, at the time, seemingly recalling a walk he’d once taken back in Kristiania (now Oslo).

“I was walking along the road with two friends

—the sun was setting

—I felt a wave of sadness—

—the Sky suddenly turned blood-red

I stopped, leaned against the fence

Tired to death—looked out over

The flaming clouds like blood and swords

—The blue-black fjord and city—

—My friends walked on—I stood

there quaking with angst—and I

felt as though a vast, endless

Scream passed through nature”

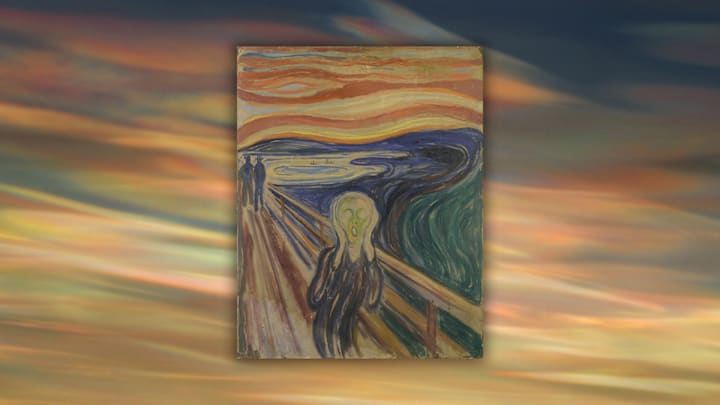

It’s universally accepted that this passage, translated from Norwegian, is related to Munch’s Expressionist masterpiece The Scream. On one version of the painting (there are four), he inscribed a variation of the text along the bottom of the frame.

What experts still debate is whether Munch was recounting a memory of his own or simply imagining a scene. He often penned literary sketches and prose poetry to complement his art, and it’s entirely possible that the blood-red sky above the blue-black fjord originated in his mind.

Perhaps the most convincing support for the theory that Munch was inspired by real life is the setting of The Scream: It looks nearly identical to Valhallveien, a fence-lined road on Ekeberg Hill with a magnificent view of Oslo and its fjord. But even if we assume that the painter did bear witness to such a striking sunset there, we’re left with another mystery.

What on Earth caused it?

Ash Interference

In 2000, climatologist Alan Robock put forth his best guess: a volcanic eruption.

When a volcano erupts, sulfur dioxide rockets into the stratosphere and lingers there in the form of tiny particles called sulfate aerosols, which—along with ash—can be borne across the globe by wind. As the sun sets, its rays must travel farther through the atmosphere than they do during the day, and we’re only able to see the longer wavelengths of light: yellows and reds, as opposed to blues. Ash and sulfate aerosols make that journey even harder, so volcanic sunsets can be especially bright red.

Though Robock proposed the June 1892 eruption of Indonesia’s Mount Awu as the potential cause of those “flaming clouds like blood and swords,” Munch’s original diary entry predated that event, and Robock eventually abandoned the idea in favor of one suggested by a trio of researchers in 2004: Krakatoa.

The August 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, an Indonesian volcanic island, is one of history’s most devastating volcanic eruptions, with a death toll of roughly 36,000 people and an ash cloud that spanned some 275 miles. Blazing sunsets were seen all over the world for years after the disaster—including some in Norway.

The researchers, led by astronomer Donald Olson, unearthed reports from the UK’s Royal Society with records of fiery twilights in Oslo from late November 1883 into the following February. During that stretch, Munch was a barely-20-year-old bohemian splitting studio space in Oslo with several peers. This bohemian era would later inspire many paintings in his collection The Frieze of Life, which, as Olson et al. pointed out, includes The Scream.

For years, the Krakatoa theory enjoyed supremacy as the likeliest origin story for Munch’s greatest gift to art—until 2017, when three Norwegian researchers came forward with a scintillating alternative.

Making Waves

If temperatures in the stratosphere fall below the ice frost point—around –120°F or so—water particles can freeze and form nacreous clouds, or mother-of-pearl clouds. (Nacreous comes from nacre, another term for mother-of-pearl.) They get their name from the iridescence created when those ice crystals diffract light, which can make for a pretty stunning sunset.

Because nacreous clouds can only exist in such frigid conditions, they’re not often seen outside polar regions. But not often isn’t never—and observations of nacreous clouds in southern Norway were recorded on a number of occasions throughout the 1880s and early 1890s.

Norwegian meteorologist Svein M. Fikke and his fellow researchers posited that Munch may have been among the observers in Oslo at some point during that era, and the hypothesis was soon championed by other investigators. Even Robock changed his tune: He co-authored a 2018 paper with atmospheric physicist Fred Prata and environmental writer Richard Hamblyn in which they demonstrate through color analysis that The Scream’s sky more closely matches a mother-of-pearl sunset than a volcanic one.

One salient point on the board for nacreous clouds is that they, like the layers in The Scream, are quite wavy. “This is generally not seen in red sunsets and volcanic sunsets, where the cloudless sky tends to be variegated and the sky with clouds tends to have variations but little or no waviness,” Prata et al. wrote. They also noted that if Munch was illustrating nacreous clouds, The Scream “in all likelihood would represent the first graphical depiction of a type of cloud largely unknown to meteorology at the time.”

The researchers did acknowledge the impracticality of applying scientific color analysis to Expressionist art. Maybe Munch’s palette lacked what he needed to duplicate the hues of a volcanic sunset, or maybe he just never intended to duplicate them. After all, The Scream is much more concerned with depicting a mental state than a landscape. Not that an artwork can’t do both—and it’s hard to see Munch’s magnum opus next to nacreous clouds without noticing the resemblance.