Anyone with a passable grasp of the 20th-century literary landscape can probably spout off a handful of facts about Virginia Woolf. Her novels include To the Lighthouse and Mrs. Dalloway. She’s known for her stream-of-consciousness writing style. Her relationship with Vita Sackville-West defied gender expectations. She died by suicide.

That’s how it often goes with iconic authors; they get distilled into easily digestible beats and buzzwords, their personhood more or less eclipsed by what they wrote and represented. But what was Virginia Woolf really like? How did she spend her time when she wasn’t penning era-defining fiction? How did her private writing differ from her published works, and how can examining that distinction deepen our understanding of the latter?

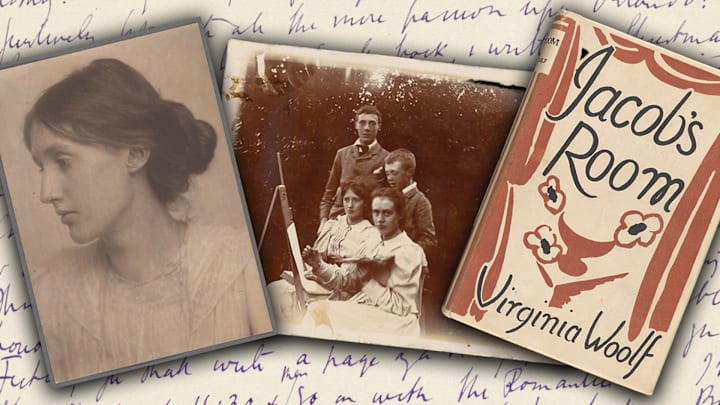

The New York Public Library is currently hosting an exhibition that holds the answers to all those questions and more. Virginia Woolf: A Modern Mind is a sweeping exploration of Woolf’s life and legacy through unpublished letters, early drafts, and other archival materials from the library’s Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature.

“For Woolf, writing was both a lifelong career and a cathartic act. It was a craft that she honed into commercial success, but it was also a tool that she used in pursuit of emotional wellbeing,” Berg Collection curator Carolyn Vega, who organized the exhibition, tells Mental Floss. “I find this both relatable and encouraging, and I hope that, through glimpses into Woolf’s diaries, drafts, and family photographs, visitors are inspired to pick up a new Woolf novel (or old favorite!) for the emotional depth and the lyrical beauty they offer. And Woolf is fun, too—see the very fun 300-year romp of Orlando.”

Dispersed throughout the exhibition are audio clips from a conversation between two contemporary authors, Brandon Taylor and Francesca Wade. As Vega explains, “Brandon Taylor is a fiction writer whose work, notably his spectacular novel Real Life, is all about exploring the deep reality of characters, much in the spirit of Woolf. Francesca Wade approaches Woolf’s writing from another angle, as a critic. She’s also interested in the places, relationships, and the context for great writing, as seen in her book Square Haunting. When faced with an original document or photograph, different details jumped out to each writer, sparking a lively and insightful discussion.”

The exhibition—including Taylor and Wade’s dialogue—has been digitized for the perusal pleasure of anyone with an internet connection. But if you do happen to be in Manhattan between now and March 5, you can see it firsthand in the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building’s Wachenheim Gallery. Here are five fascinating takeaways.

1. Virginia Woolf and her husband ran a printing press.

In 1917, Virginia and Leonard Woolf—with zero printing experience between them—founded Hogarth Press. Virginia took care of typesetting and book-binding, and Leonard was in charge of page order, ink, and actually operating the handpress. The formulaic nature of the tasks helped mitigate the frustration and malaise Virginia so often experienced when she was working on her own fiction.

“Now the point of the Press is that it entirely prevents brooding; and gives me something solid to fall back on. Anyhow, if I can’t write, I can make other people write; I can build up a business,” she articulated in a 1924 diary entry.

Hogarth Press’s first publication was Two Stories, one by Leonard (“Three Jews”) and the other by Virginia (“The Mark on the Wall”). Over the next decade or so, the press became equal parts prolific and broad, publishing everything from Julia Margaret Cameron’s photographs and T.S. Eliot’s poems to the first English-language edition of Freud’s The Ego and the Id.

2. Virginia Woolf’s sister designed many of her book covers.

Woolf’s sister, Vanessa Bell, was an artist who designed much of the cover art for Hogarth’s works, including Woolf’s own. “The sisters supported one another professionally and were deeply entwined their whole lives, despite having different temperaments,” Vega explains. British diplomat Sydney Waterlow once described Bell as “icy, cynical, artistic,” while Woolf was “much more emotional & interested in life rather than beauty.” Unsurprisingly, they did weather the occasional period of discord over the course of their decades-long personal and professional relationship.

“When Virginia Woolf had a flirtation with Vanessa’s husband: that caused tension. When Vanessa nearly refused to collaborate on future projects following (what she thought of as) a bad printing job by the Woolfs’ Hogarth Press: that caused tension,” Vega says. “But they were not just siblings, they were real friends, too, and they kept working together until Woolf’s suicide in 1941.”

3. Woolf often wrote in purple ink.

A few pages on display were written in purple ink—a color that Woolf favored specifically for diary entries, manuscripts, and love letters. She seemed to feel that black failed to capture tonal nuances.

“I must buy some shaded inks—lavenders, pinks, violets—to shade my meaning. I see I gave you many wrong meanings, using only black ink,” she wrote to Sackville-West on January 19, 1941. “It was a joke—our drifting apart. It was serious, wishing you’d write. … No, no, I must buy my coloured inks.”

4. She once visited Haworth, home of the Brontë family.

In 1904, Woolf, aged 22, took a trip to Haworth, the West Yorkshire village where Charlotte, Emily, and the other Brontës spent their formative years. Though the family home itself wouldn’t become a museum until the late 1920s, the Brontë Society had been running a museum in town since 1895; and Brontë fans had been making pilgrimages to Haworth even while Charlotte was still alive (she died in 1855).

Woolf wrote about her visit in an essay published in The Guardian, an early draft of which is featured in the NYPL exhibition. In it, she interrogates the merits of literary tourism, deeming that “The curiosity is only legitimate when the house of a great writer or the country in which it is set adds something to our understanding of his books.” She decided that Haworth fit the bill: “Haworth expresses the Brontës; the Brontës express Haworth; they fit like a snail to its shell.”

Woolf’s own abode in East Sussex is now a prized pin on the maps of many a literary tourist. She and Leonard purchased the bucolic cottage—named Monk’s House—in 1919 because of its sprawling garden. “Every time she published a new book and got new royalties, she would build a new bathroom extension or something, and it’s a really moving place to go,” Wade mentions in her conversation with Taylor.

5. Woolf wasn’t as somber as people think.

Woolf’s deep-set eyes and long, narrow face give her an air of melancholy in photos, and the tragic parts of her life—the deaths of multiple family members, sexual abuse by her half-brothers, her lifelong struggles with mental illness, and her death by suicide—reinforce the notion that she was a perpetually intense and somber person.

“Depressed, she certainly was at times, but she was not generally sad. Quite the contrary,” her nephew Cecil Woolf said in a 2004 address. “Leonard remembered that during the First World War when they sheltered in the basement of their London lodgings from enemy bombing, Virginia made the servants laugh so much that he complained he was unable to sleep. My own recollection of her is of a fun-loving, witty and, at times, slightly malicious person.”

The NYPL exhibition features photos and letters that help convey Woolf’s oft-overlooked penchant for levity. “I love the photograph of Woolf on the beach with her future brother-in-law, Clive Bell. She’s wearing a knee-length bathing suit, smiling broadly, and seems to be almost mid-frolic,” Vega says. “I always thought of Woolf as a serious figure, with a formidable mind for language. That’s true, but she also knew how to have a good time.”