There’s a word for the final remaining member of a species: endling, which was suggested in a letter written to Nature in 1996. “An orphan is someone, usually a child, with no living parents. A foundling is someone, usually an abandoned baby, with no known parents. We do not have one word to describe the last person surviving or deceased in a family line, or the last survivor of a species,” the authors wrote. They felt endling was appropriate because “end- has several meanings, including ‘extinction’ and ‘finish, concluding part’; -ling is a suffix added to denote ‘connected with the primary noun’ but also includes line and lineage.”

And once that lonely endling is gone, a species becomes extinct. There are so many animals that have gone extinct through the ages that we’re choosing to focus just on creatures that went extinct relatively recently: from 1800 onward. So even though this list—which is adapted from the above episode of The List Show on YouTube—covers animals that went the way of the dodo, we won’t be talking about the dodo itself, which, incidentally, went extinct in the late 17th century.

Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)

Did you know that penguins weren’t necessarily the first penguins? That honor might belong to the great auk, Pinguinus impennis. These 2.5-foot-tall flightless creatures lived in the North Atlantic and were once so plentiful that a sailor visiting one of their island habitats wrote that “a man could not go ashore … without boots, for otherwise they would spoil his legs, that they were entirely covered with those fowls, so close that a man could not put his foot between them.”

But the birds were easy prey on land (where they went to mate) and at sea, which is where they spent the majority of their time: Per Britannica, they were “often being driven up a plank and slaughtered on their way into the hold of a vessel.” People ate the animals or used them for bait—and one of the last of the species was executed for being a witch.

The story goes that, in the 1840s, some sailors were off the coast of a Scottish island when they spotted a snoozing great auk. By that time, there were not a lot of auks left, so this bird was worth a pretty penny. The sailors decided to capture it alive. The bird woke up and began to scream—and then rain started to fall. The men headed to a hut to ride out what became a terrible storm. They spent three days there with the auk, which began squawking when anyone got too close. At that point, they came to the conclusion that the auk wasn’t a bird at all, but a witch—and the only way to stop the storm was to kill it. They dispatched the bird by beating it to death. It was likely the last great auk in Great Britain, and the entire species had been wiped out by the middle of the century.

You May Also Like ...

- 10 Tragic Stories of Extinct Animals

- 6 Animals That Were the Last of Their Species

- 25 Species That Have Made Amazing Comebacks

Add Mental Floss as a preferred news source!

Lonesome George, the Pinta Island Tortoise (Chelonoidis niger abingdonii)

Lonesome George was the last Pinta Island tortoise in the Galapagos Islands. Giant tortoises were once plentiful in the Galapagos; Charles Darwin would even hop on their backs to hitch a ride, and said he “found it very difficult to keep [his] balance.”

Sailors brought the animals on their ships to provide food and oil on voyages; this hunting ravaged the population, which once numbered 200,000 animals. While the population has been steadily recovering over the past few decades, George’s particular subspecies was thought to be extinct due to hunting. But in 1971, a Hungarian scientist studying snails on the island spotted George. He was brought to the Tortoise Center on Santa Cruz Island the following year.

Though scientists hoped to find a female Pinta tortoise for George to breed with, their search was fruitless, and he was given the moniker Lonesome George. George died of natural causes in his sleep in 2012; his caretakers estimated that he was more than 100 years old.

Ivory-Billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis)

The ivory-billed woodpecker was the third-largest woodpecker in the world, and it could be found in forests in the southeastern U.S. and Cuba (though some believe the Cuban birds were a distinct species or subspecies). Unfortunately, the birds required vast swaths of forest to survive, so habitat destruction due to logging had dealt its population a severe blow by the 1800s. By the late 1930s, it was estimated that there were probably only two dozen of the birds left. The last official sighting in the United States was of a lone female in 1944; the last in Cuba was in the 1980s.

But some wildlife researchers—among them folks from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology—believe they’ve spotted the birds in eastern Arkansas, and in 2005 went so far as to declare the woodpecker not extinct at all on the basis of those sightings and video they’d captured. More recently, people claim to have caught the birds on video in 2020 and 2021 in Louisiana.

The issue is, it’s hard to tell from grainy, far away footage if the birds are ivory-billed woodpeckers or the similar-looking pileated woodpecker. And one bird expert believed one of the animals caught on video wasn’t a woodpecker at all, but a wood duck. In 2021, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service opened up a list of species they planned to declare extinct to public comment, including the ivory-billed woodpecker. But the debate on the issue was so intense that they ended up postponing the ivory-billed woodpecker decision altogether pending further investigation.

Turgi the Polynesian Tree Snail (Partula turgida)

January 1996 was a sad time for keepers at the London Zoo. It was the month that Turgi , the last Polynesian tree snail of the species Partula turgida, died. The species was taken out by the rosy wolfsnail, which had been brought to the islands by colonizers who were hoping to kill off another invasive species, and then by a parasite, which wiped out the captive population. Turgi’s keepers put “1.5 million years BC to January 1996” on the endling’s tombstone—a sad epitaph indeed.

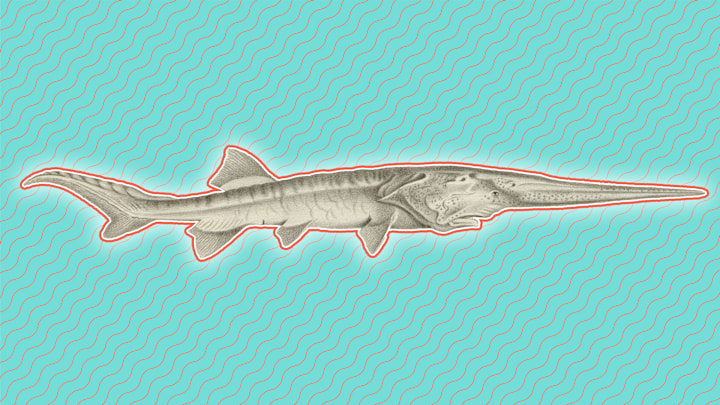

Chinese Paddlefish (Psephurus gladius)

The Chinese paddlefish may have been the world’s largest freshwater fish: It could grow up to 23 feet long and weigh nearly 1000 pounds and was found in rivers around China. But overfishing cut its numbers dramatically, and when the Gezhouba Dam was built on the Yangtze River in the 1980s, it spelled the beginning of the end for the species. The dam blocked the fish’s route to its spawning grounds. Scientists believe the fish was functionally extinct—meaning its population wasn’t significant enough to impact its ecosystem or robust enough to sustain the species—around 1993. The last Chinese paddlefish was spotted in 2003.

Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius)

The passenger pigeon was once so plentiful that a Wisconsin newspaper described the sound of the arrival of a flock in 1871 thusly:

“Imagine a thousand threshing machines running under full headway, accompanied by as many steamboats groaning off steam, with an equal quota of R.R. trains passing through covered bridges—imagine these massed into a single flock, and you possibly have a faint conception of the terrific roar.”

It’s believed that there may have been as many as 3 to 5 billion passenger pigeons at one point, making it, in the words of the Florida Museum, “the most abundant bird in North America” into the 1870s. The last passenger pigeon, a bird named Martha that lived at the Cincinnati Zoo, died in September 1914. So what happened?

Blame it on the railroads. Not only did the land needed for trains lead to deforestation and loss of the birds’ habitat, the trains also allowed hunters to follow the birds around the country. Passenger pigeons’ survival strategy involved flying in huge flocks, which made them very easy for hunters with guns to kill in huge numbers. According to the Audubon Society, other methods for killing the pigeons were suffocating the birds by burning sulfur or poisoning them by soaking corn in whiskey. Those hunters also decimated the birds’ nesting grounds, killing adult birds and squabs alike. The birds simply could not survive the dual attack on their populations and nesting grounds. If there’s a silver lining to this terrible tale, it’s that the passenger pigeon’s demise helped lead to the modern conservation movement.

Warrah (Dusicyon australis)

When Charles Darwin visited the Falkland islands in the South Atlantic in the 1830s, he issued a dire warning about the warrah, also known as the Falklands wolf or Falklands fox: “This fox will be classed with the dodo as an animal which has perished from the face of the earth.” And he was right.

The warrah was the only land mammal on the Falkland islands, and how it got there is a bit of a mystery. The idea that humans brought over the warrah’s ancestors a long time ago is popular, but genetic evidence gives an awkward date for that. It might have made the leap during the last glacial maximum via land, ice, or some combination, but then you have to explain why no other land mammals seem to have made the trip. Both sides have their explanations, but it’s an open question.

No matter how it got there, it was just minding its own business when people settled in the Falkland Islands in the 1700s. But those people thought the warrah was going to eat their farm animals. They liked their fur, too. Hunters made quick work of the warrah, which were gone by 1876.

Scottish Wildcat (Felis silvestris silvestris)

In 2023, scientists announced that Scotland’s Scottish wildcat—the only wildcat left in Great Britain—is believed to be “genomically extinct.”

What does that mean? Scottish wildcats and domestic cats co-existed for a couple thousand years, but they only began interbreeding around 70 years ago. The theory about why they did so is that hunting drove the wildcats up into the highlands, where the population initially recovered. But disease in their prey as well as people encroaching on their habitat decimated the population until there may have been only 30 or so animals left. For many Scottish wildcats, the only other cat they would have come upon during their limited mating season would have been a domestic one.

And make no mistake, though the Scottish wildcat looks like a grumpy tabby, they are not your common housecat: They’re larger and stockier, their legs are longer, and their tails are thicker. And though people might joke about their cats being aloof, Scottish wildcats really are—they’re solitary creatures that can’t be tamed.

The interbreeding between the species inevitably corrupted the wildcat’s genome. As Science explains, a recent study found that “starting in the mid-1950s, more than 5 percent of the genetic markers in Scottish wildcats began to resemble those of domestic cats. After 1997, that figure jumped to as high as 74 percent,” leading the study’s authors to conclude that the current population of Scottish wildcats is actually a “hybrid swarm.”

Scientists are desperately trying to save the species, though. The DNA markers of the captive population of Scottish wildcats is just 18 percent domestic, and a program to breed and release the cats into the wild just let its first wildcats run free in 2023. But some believe the animals are too far gone to save, and that a better option is to grab wildcats from Europe and bring them to Scotland.