Editor's Note (06/24): When E. Bryant Crutchfield passed away at the age of 85 in 2022, he left behind a legacy—and more than a little controversy. After mainstream media outlets cited this article to characterize Crutchfield as the innovator behind the Trapper Keeper, a former Mead employee named Jon Wyant, 84, came forward to assert his role in the design of the product. Crutchfield, Wyant alleged, had taken too much credit. Wyant claimed to be the sole creator of the Trapper Keeper.

At the time of the product’s release, Wyant was Director of New Product Development at Mead and tasked with creating and improving school supplies for the company. In Wyant’s recollection, Crutchfield gave him little direction other than to say he wanted a binder to hold folders with vertical pockets. Crutchfield cited Wyant as giving the Trapper Keeper its name and logo. But Wyant said that he was also responsible for the innovative diagonal (versus the then-standard vertical) pockets, the notepad with built-in pencil clip, the snap enclosure, and the overall design of the Trapper Keeper.

While no patent on the Trapper Keeper itself appears to exist, patents for those elements do. It is Wyant, not Crutchfield, who is named on the patent for the diagonal folder (US3870223A, granted in 1975) and on the patent (with fellow Mead employee Paul Seaborn) for the notepad with pencil clip (US3968546A, granted in 1976).

During his 2013 conversation with Mental Floss, Crutchfield explained he sometimes made suggestions for products and gave them to others to design without concern for being named on the patent, a plausible but not provable claim.

Wyant’s story was profiled in a November 2023 segment of This American Life. After speaking to Wyant, Wyant’s daughter Jackie Harris, Crutchfield’s children, and Mead employees, host Phia Bennin reported that Crutchfield likely deserved some, but not all, of the credit for the product.

Mental Floss has also spoken with Jon Wyant and Jackie Harris. Wyant maintains he was the sole designer of the Trapper Keeper with no input from Crutchfield. Wyant has also retained possession of what appears to be the original Trapper Keeper prototype, which he had made at a Mead-affiliated plant in Missouri.

“As far as the actual product, [he did] practically nothing,” Wyant tells Mental Floss of Crutchfield’s involvement in the product design. “He was a marketing manager. He would explore the market and make recommendations … the design of the Trapper Keeper he had almost nothing to do with.”

Mental Floss also reached out to some former Mead employees. One described trying to figure out who had the initial idea for the Trapper Keeper as a “chicken and egg scenario.” He also stated that “everyone I knew” believed Wyant was behind the actual design of the Trapper Keeper, though this person was not with the company himself at the time. Most stopped short of assigning sole credit to either Crutchfield or Wyant. They described Wyant as a design-oriented professional who knew how to take ideas and turn them into items that could be mass-manufactured. It was then up to Crutchfield to market and advertise those products.

A spokesperson for Mead, which is now owned by ACCO Brands, had no comment on the matter; surviving documentation yields little in the way of conclusive evidence. One key brainstorming session that took place for Mead employees in Boston in May of 1976 targeted a “locker item” that would allow students to carry home sections as well as a “holding unit where specific or individual components can be pulled for specific class or subject use.” One memo notes that Wyant’s “top priority development” was a “multi-use product: locker item.” Many ideas were discussed at this session, and it's difficult to parse whether some, all, or none ended up incorporated into the Trapper Keeper.

Crutchfield headed up these meetings; Wyant attended them, though he said there was little actionable discussion going on and he didn’t pay the sessions much mind. It’s possible Crutchfield voiced his desire for a school-friendly product and invoked vertical pockets, leaving Wyant to bring it to fruition.

Wyant also claims to have invented the System, Organizer, and Data Center, binders that were precursors to the Trapper Keeper and released between 1972 and 1976. The products share many of the same traits as the Trapper Keeper. While the binders themselves are not patented, each used patented elements like the diagonal folder that are credited to Wyant. There’s no question the Trapper Keeper was the offspring of these folders, this time designed for a juvenile market, and that Wyant was best equipped to assemble a practical product.

Given Crutchfield’s documented research into school trends, it’s within reason to believe he sought to develop a product with traits such as modular components and spill-proof folders to meet the market. The actual design may have then been left to Wyant, who had already crafted and patented key elements of what would eventually become known as the Trapper Keeper.

The article below appears as it was originally published in 2013. It was and remains the genesis of the Trapper Keeper through the eyes of Crutchfield and should be taken as such, though we’ve now noted when Crutchfield’s claims subsequently came under scrutiny. We have also changed language to reflect his disputed authorship.

Given Wyant’s esteemed reputation within Mead, it’s likely his role in developing and designing the Trapper Keeper was not properly attributed in Crutchfield’s telling. Giving anyone sole credit, however, is difficult considering Crutchfield is no longer able to relate his side of the story or respond to Wyant’s recollections. The only certainty is that the Trapper Keeper would not exist as we know it today without the efforts of both Jon Wyant and E. Bryant Crutchfield.

When E. Bryant Crutchfield began test-marketing a new school notebook in 1978, he thought it would be useful to insert a feedback card into each one. Kids who purchased the organizer—which was called the Trapper Keeper—found a slip that promised them a free binder if they mailed in their comments.

Approximately 1500 cards were returned. Under “Why did you purchase the Trapper Keeper rather than another type binder?” respondents said things like:

“I heard it was good. My girlfriend had one."

“So when kids in my class throw it, the papers won’t fly all over.”

“My mother got it by mistake but I'd seen it on TV, so I decided to keep it.”

“Instead of taking the whole thing you can take only one part home.”

“Because they keep your papers where they belong. They’re really great—everybody has one.”

But Crutchfield’s favorite comment came from a 14-year-old named Fred. Fred wrote that he had bought the Trapper Keeper rather than another binder to “keep all my shit, like papers and notes.”

“Kids that age are very open and honest,” Crutchfield chuckles.

Launched in 1978 by Mead (now part of ACCO Brands), Trapper Keeper notebooks were a departure from the sterile, generic supplies that populated school lockers and desks. Brightly colored three-ring binders held folders called Trappers and closed with a satisfying button snap. From the start, they were an enormous success: For several years after their nationwide release, Mead sold over $100 million of the folders and notebooks a year. To date, more than 75 million Trapper Keepers have flown off store shelves.

But in the late 1970s, the people at Mead couldn’t have known that their product would eventually garner such cultural significance. In fact, Crutchfield was just looking for the next back-to-school item, and he did it the old-fashioned way—through market research. “[The Trapper Keeper] was no accident,” he tells Mental Floss. “It was the most scientific and pragmatically planned product ever in that industry.” In a sense, the Trapper Keeper became one of the few influential designs that represented the ideas, needs, and impressions of the masses. Kids like Fred were part of a creative committee that helped generate one of the most enduring organizational products of all time.

Situation Analysis

As director of New Ventures at Mead, part of Crutchfield’s job was to identify trends in the marketplace. In 1972, Crutchfield’s analysis, conducted with someone at Harvard, showed there would be more students per classroom in the coming years. Those students were taking more classes, and had smaller lockers.

Fast forward a few years, when Crutchfield’s analysis revealed that sales of portfolios, or folders, were increasing at 30 percent a year. Thinking back to that Harvard report, a lightbulb went off. “You can’t take six 150-page notebooks around with you, and you can’t interchange them,” Crutchfield says. “People were using more portfolios, so I wanted to make a notebook that would hold portfolios, and they could take that to six classes.”

Crutchfield was speaking with his West Coast sales representative about what he planned to do when another piece fell into place. Portfolios in notebooks were a great idea, the rep said, but why not make the pockets vertical instead of horizontal?

Folders with vertical pockets, called PeeChees (as in, peachy keen), had been around since the 1940s and were sold on the West Coast, but they had never made the leap across the Rockies—so Crutchfield was doubtful. “I said, ‘They only sell on the West Coast, and what’s the real benefit of a vertical pocket?’” Crutchfield remembers. “[The rep] said, ‘When you close it up, the papers are trapped inside—they can’t fall out. If you’ve got a horizontal pocket portfolio, you turn it upside down, and zap! [The papers] fall out.’”

Crutchfield was convinced and got to work. First, he took sketches of the portfolios and notebooks to a group of teachers to find out if there was truly a need for that kind of thing. The group said that student organization was a major problem, and the teachers would welcome any product that would help in that regard.

Next, Crutchfield created a physical mock-up. (Ed. Note: Wyant asserts he created the prototype Trapper Keeper.) Unlike the PeeChee—which had straight up-and-down vertical pockets—Crutchfield’s portfolios had angled pockets, with multiplication tables, weight conversions, and rulers on them. “It was like a textbook inside,” he said. That was followed by a three-ring binder that held those portfolios and closed with a flap. Students could drop the notebook, and the contents would stay securely in place.

So Crutchfield had a mock-up of his product, but he still didn’t have a name. That came from Director of New Product Development Jon Wyant. “I said, ‘I need a name for this damn thing. Have you got any ideas?’” Crutchfield remembers. The next day, they were drinking a martini with lunch when Wyant said, “Let’s call the portfolio the Trapper.”

“What are we going to call the notebook?” Crutchfield asked. “The Trapper Keeper,” Wyant replied.

“Bang!” Crutchfield says. “It made sense!” And that was that.

Testing the Market

With the product named, and a prototype created (the “Trapper Keeper” logo stuck on in press-on-type, and the design—soccer players—held on with tape), Crutchfield went to the next step: more focus group testing. He and other Mead representatives went to schools with the Trappers and Trapper Keeper, talking to students and teachers to get feedback. He also looked for input a little closer to home, from his 13-year-old daughter and 15-year-old son: “I had access to what they were doing in school,” he says, “and I saw their lockers and talked to their teachers.”

For about a year, Crutchfield conducted interviews and focus groups, tweaking the design of the Trapper Keeper along the way. “There were probably five or six iterations,” he says. (Ed. Note: Wyant claims only one physical iteration existed.) And once he was happy with the result—a PVC binder with plastic, pinchless rings (they slid open to the side instead of snapping open), a clip that held a pad and a pencil, and flap held firmly closed by a snap—it was time to run a test market, which would help them determine if the product was truly viable.

Prior to the test, Crutchfield claims he wrote a commercial and flew from Dayton, Ohio—where Mead (and now ACCO) was based—to Manhattan, where he says he hired three actors and filmed the clip for a mere $5000 in just three hours. He was short on cash, so it had to get done—but getting it done wasn’t easy. One actor in particular was having a tough time. “It was very straightforward—the kid had a notebook in his arms, and his papers fell out [when a cute girl came over],” Crutchfield says. “We were about 20 minutes away from when the camera goes off [when] he finally got it. I said ‘Wrap!’ and that was it.”

The chosen test market was Wichita, Kansas. In August 1978, Mead aired the commercial there and rolled out its Trapper portfolios and Trapper Keepers. What happened next was unexpected: “It sold out completely,” Crutchfield says.

Inside each Trapper Keeper (which came with a few Trapper folders) was a feedback card; if kids sent it in, Mead would send them a free notebook. Approximately 1500 cards were returned, and they revealed that it wasn’t just kids buying the Trapper Keepers: Adults were also buying it for record and recipe keeping.

After reviewing the test market results, it was clear that Mead had a hit on its hands. Crutchfield told Bob Crandall, the regional sales manager, “This just might be the most fantastic product we’ve ever launched. I think it’s really going to shake up the school supplies market.”

Going National With the Trapper Keeper

The company decided to roll out Trappers and Trapper Keepers nationally in the summer of 1981. To prep, Mead created a prime-time network television campaign—a pretty unusual thing for a school supply. They also ran ads in print featuring Mrs. Willard, a 9th grade teacher from Wellington, Kansas, who had recommended the Trapper Keeper to her students during the product’s run in the test market. In the ad, she summed up the benefits of using the Trapper Keeper:

“Most students keep the Trapper Keeper in their locker. Then, they just change Trappers from class to class. With no large notebooks to carry around, they travel light and easy. After school, they take the Trapper Keeper home with all the Trappers inside.”

The folders came in three colors (red, blue, and green); advertisements from the era depict the Trapper Keeper with sports and nature covers. The Trappers had a suggested retail price of 29 cents each, while the Trapper Keepers had a suggested retail price of $4.85.

“We rolled it out, and it was just like a rocket,” Crutchfield says. “It was the biggest thing we’d ever done. I saw kids fight over designs in retail.”

Growing and Changing

In its third year on store shelves, Trapper Keeper sales were still going strong. It was at that point that Mead made a design change, replacing the metal snap with Velcro. The cover design was a waterfall—a photo Crutchfield says he had snapped himself in the mountains of North Carolina.

Even though Velcro was a hot material at the time, replacing the snap with it made sense for a lot of reasons beyond that, Crutchfield remembers. One was the fact that “people had trouble finding the center of the snap to snap it,” he says. The other had to do with manufacturing. “Snaps were a lot harder—you have to put [the binder] through a machine twice to put the snap in there. Velcro was a lot easier to apply.”

Though the Trapper folders remained virtually unchanged through the years, the Trapper Keeper evolved as student needs evolved. That evolution included new designs—everything from cool cars to unicorns—which were introduced annually.

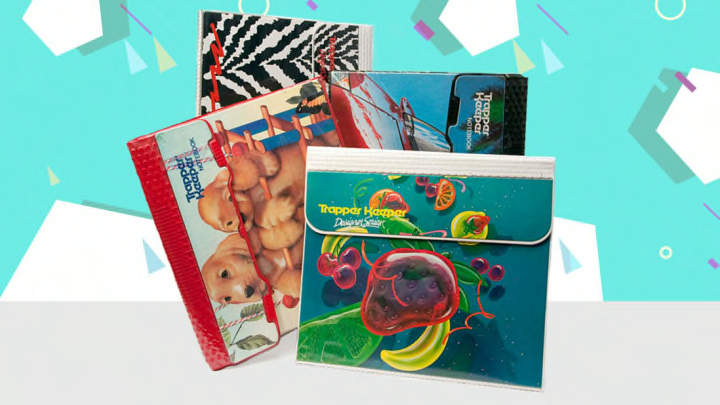

In 1988, Mead introduced the Trapper Keeper designer series—fashionable, funky, and sometimes psychedelic designs on the binders and folders that ran until 1995. “Mead employed a large amount of local illustrators to provide early artwork,” Peter Bartlett, former director of product innovation at ACCO Brands and now a professor of design management at Savannah College of Art and Design, tells Mental Floss. The company also made a deal with Lisa Frank and put her designs on Trappers and Trapper Keepers, and licensed iconic characters like Garfield and Sonic the Hedgehog for the binders. Even Lamborghini got in on the action, granting its blessing to put some of its cars on the Trapper Keeper.

Of course, anything as popular as the Trapper Keeper will almost inevitably face a backlash—but in this case, the backlash didn’t come from students. Crutchfield remembers that some teachers complained about the multiplication and conversion tables, which they said could help students cheat. “It was a controversy at one time,” he says. “One teacher said, ‘Hell, we can take the portfolios away from them while they’re doing their tests.’ Most of the teachers were very honest and said, ‘Anything that helps me pound it in their head is good.’”

Mention Trapper Keepers to your friends, and you’ll inevitably hear from someone who desperately wanted one, but couldn't have it because it was banned by their school. “The Trapper Keeper started to show up on some class lists as a ‘do not purchase’ because [teachers] didn’t like the noise of that Velcro,” Bartlett says. “[So] we switched from Velcro back to a snap.”

But in some cases, what the binders that schools were calling Trapper Keepers and banning weren’t actually Trapper Keepers. “Our research has shown that what they’re calling Trapper Keepers, [are actually] these big sewn binders that are three to four inches thick and can’t fit into a small school desk,” Bartlett says. “That’s the reason they’re on the list. When you show [the teachers] a real Trapper Keeper, with a very slim, one-inch ring fixture, it’s like, ‘Oh no, that’s not what I’m talking about. I don’t have any problem with that!’”

Though it became less popular after the mid-1990s, the Trapper Keeper has remained an important part of Mead’s back-to-school line of products—though it has undergone some modifications. “The main change is that we went away from PVC, as most health-conscious companies are trying to do,” Bartlett says. “So it looks slightly different because it’s made out of polypropylene and sewn fabric, but the function is essentially the same.” One line, which was introduced in 2007 and available for a year, was even customizable. “They had a clear piece of plastic in the front,” says Richard Harris, former program manager of industrial design at ACCO. “There was a printed pattern behind it, but then you could put whatever you wanted in that clear sleeve in the front.”

But the cool, psychedelic designs of the early 1990s aren’t as big a focus in the Trapper Keeper line these days. “Trapper has evolved a little bit to relying strongly on a color coding system of organization for students,” Bartlett says. But it’s not all work and no play: After a product relaunch in 2014, the company added new Trapper Keeper designs, including Star Wars and Hello Kitty, in 2015.

The Trapper Keeper's Legacy

So why, exactly, do people still love the Trapper Keeper, many decades after they last had one? For Bartlett, it all boils down to what the Trapper Keeper allowed kids to do—and he's not talking about keeping organized. “It was fun to be able to show your personality through the binder that you had,” Bartlett says. “You don’t really remember a notebook or the pens and pencils you used. But maybe you remember your [Trapper Keeper].” Harris says that the binder “wasn’t a regular school product. When you got it, it was almost like a Christmas present. You were excited to have it.”

It’s also a prominent pop culture touchstone: Trapper Keepers have been featured on Family Guy, South Park, Full House, Stranger Things, and Napoleon Dynamite. They were even transformed into a Trivial Pursuit game piece.

These organizational devices would come to define childhoods across North America, and adults who had them remember their Trapper Keepers fondly. (And those who didn’t have them often remember exactly which one they wanted.) Joshua Fruhlinger at Engadget called it “the greatest three-ring binder ever created … Trapper Keepers—the way they combined all of one's desktop tools—were an early incarnation of the smartphone.” There is robust business in vintage Trapper Keepers on eBay, where unused binders with tags start at $150 (those in good condition are priced at $75).

“When I first went to work, all school products were drab and boring,” Crutchfield says. “[Trapper Keepers were] more functional and more attractive, with oodles of choices—therefore fun to have. And I had a lot of fun making them fun!”

A version of this story ran in 2013; it has been updated for 2024 following allegations from Jon Wyant, a former Mead employee, who claims that E. Bryant Crutchfield took too much credit for his role in the product’s creation. You can read the full editor’s note at the top of this article.