Computing scientists at the University of Alberta recently made a bold claim: They say they’ve identified the source language of the baffling Voynich Manuscript, and they did so using artificial intelligence.

Their study, published in Transactions of the Association of Computational Linguistics [PDF], basically states that an AI algorithm trained to recognize hundreds of languages determined the Voynich Manuscript to be encoded Hebrew. On the surface, this looks like a huge breakthrough: Since it was rediscovered a century ago, the Voynich Manuscript’s indecipherable text has stumped everyone from World War II codebreakers to computer programmers. But experts are hesitant to give credence to the news. “I have very little faith in it,” cryptographer Elonka Dunin tells Mental Floss. “Hebrew, and dozens of other languages have been identified before. Everyone sees what they want to see.”

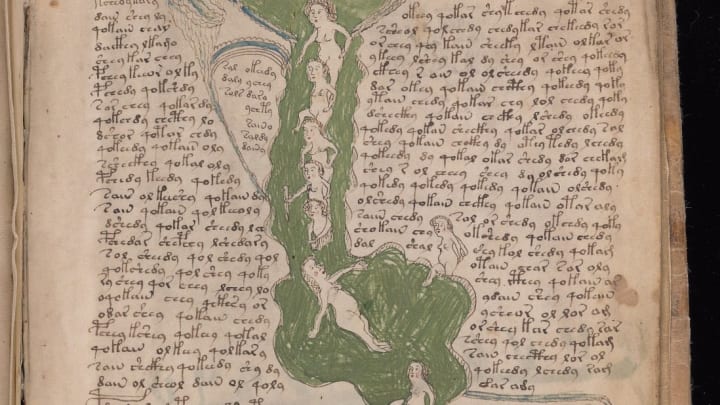

Anyone who’s familiar with the Voynich Manuscript should understand the skepticism. The book, which contains 246 pages of illustrations and apparent words written in an unknown script, is obscured by mystery. It’s named for Wilfrid Voynich, the Polish book dealer who purchased it in 1912, but experts believe it was written 600 years ago. Nothing is known about the person who authored it or the book’s purpose.

Many cryptologists suspect the text is a cipher, or a coded pattern of letters that must be unscrambled to make sense. But no code has been identified even after decades of the world’s best cryptographers testing countless combinations. With their study, the researchers at the University of Alberta claim to have done something different. Instead of relying on human linguists and codebreakers, they developed an AI program capable of identifying the source languages of text. They fed the technology 380 versions of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, each one translated into a different language and enciphered. After learning to recognize codes in various languages, the AI was given some pages of the Voynich Manuscript. Based on what it had seen already, it named Hebrew as the book’s original language—a surprise to the researchers, who were expecting Arabic.

The researchers then devised an algorithm that rearranged the letters into real words. They were able to make actual Hebrew out of 80 percent of the encoded words in the manuscript. Next, they needed to find an ancient Hebrew scholar to look at the words and determine if they fit together coherently.

But the researchers claim they were unable to get in touch with any scholars, and instead used Google Translate to make sense of the first sentence of the manuscript. In English, the decoded words they came up with read, “She made recommendations to the priest, man of the house and me and people." Study co-author Greg Kondrak said in a release, “It’s a kind of strange sentence to start a manuscript but it definitely makes sense.”

Dunin is less optimistic. According to her, naming a possible cipher and source language without actually translating more of the text is no cause for celebration. “They identify a method without decrypting a paragraph,” she says. Even their method is questionable. Dunin points out the AI program was trained using ciphers that the researchers themselves wrote, not ciphers from real life. “They scrambled the texts using their own system, then they used their own software to de-scramble those. Then they used it on the manuscript and said, ‘Oh look, it’s Hebrew!’ So it’s a big, big leap.”

The University of Alberta researchers aren’t the first to claim they’ve identified the language of the Voynich Manuscript, and they won’t be the last. But unless they’re able the decode the full text into a meaningful language, the manuscript remains as mysterious today as it did 100 years ago. And if you agree with cryptographers like Dunin who think the book might be a constructed language, a detailed hoax, or even a product of mental illness, it’s a mystery without a satisfying explanation.