The body of St. Nicholas—the man Santa Claus is based on—resides in Bari, Italy. The church claims that the bones of the saint are secreting a sweet-smelling water called manna. Every May 9th, the priests remove a small amount of this liquid, which is said to contain healing powers. You can purchase some in the church gift shop. Here’s a video of the priest removing the manna in 2012:

What’s going on here? Why is liquid coming out of St. Nicholas’s tomb?

No Bones About It

The body isn’t even supposed to be in Italy. St. Nicholas was a Greek bishop who lived in Turkey during the 4th Century. Like many early saints, little is known about his life. It’s said that when his wealthy parents died, Nicholas gave away his inheritance to the sick and needy, thus gaining a reputation for generosity. In one story, a poor man was considering selling his three daughters into slavery because he couldn’t afford their wedding dowries. On three separate nights, Nicholas tossed a bag of gold through the window (chimneys hadn’t been invented yet) and saved the daughters from ugly fates. This story is the seed for Santa Claus.

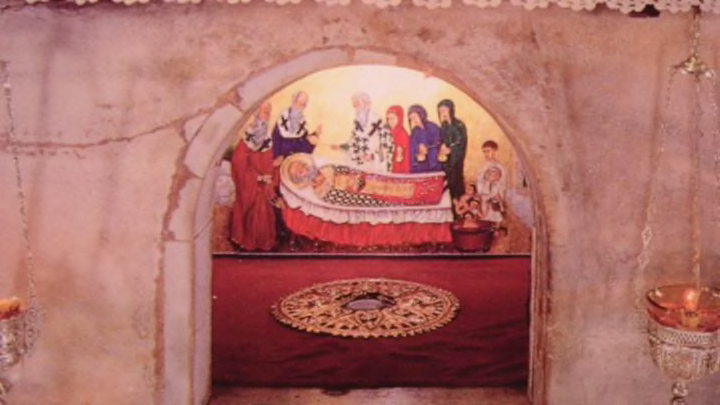

When Nicholas died on December 6, 343 AD—still widely celebrated as Saint Nicholas Day—his grave in Myra became a popular pilgrimage site. In 1087, Italian sailors stole the body and brought it to Italy, supposedly to protect it from invading Seljuk Turks. Today, Bari still celebrates this theft with a citywide festival that includes the removal of the manna and a parade where a statue of St. Nicholas is carried from the harbor to the Basilica Di Nicola. (But not everyone revels in this ancient larceny: Turkey has demanded the body be returned, setting off a debate about who has the right to archeological remains.)

In the 900 years that Nicholas has been in Bari, the remains have been examined only once. In 1953, the tomb was opened for renovations and the bones were measured, x-rayed, and diagramed. At the time, they were found to be in delicate condition. Many bones were missing.

Based on those measurements, Santa Claus was not a jolly fat man, but thin and short with big eyes and an unusually large head. (Here’s a 3D reconstruction of his face.) He also had a broken nose, which support stories that Nicholas had a temper—supposedly, he punched a heretic during the First Council of Nicea.

So what about claims that the body gives off manna? The church says the bones have always leaked. When St. Nicholas died, the tomb in Turkey was supposed to produce fragrant oil that healed everyone who touched it. When the bones were moved to Bari, they continued to ooze liquid, which was bottled up and sent all over the world. Even when the bones were taken out in 1953, they continued to perspire so much that the linen cloth below them was soaking wet.

The Plot Thickens

Bari isn’t the only place that has St. Nicholas’s bones. San Nicoló al Lido in Venice also has some. For years, the two churches argued about who could claim the real Santa Claus. In 1992, Luigi Martino, who also led the Bari study, examined the Venice bones and said they were likely to be the same person. The explanation, such that it is, is that the original sailors may not have removed all the bones from Turkey and the rest were brought to Venice during the first crusades.

Oddly enough, the Venice bones don’t seep liquid, suggesting that whatever the phenomenon is, it’s only happening in Bari. Venice also has a bottle of manna dating back to the 1100s—or so the church thought. In 2002, scientists did analysis and radiocarbon dating on a sample of the manna and found that it was vegetable oil from the 1300s.

Experts say it’s unlikely that St. Nicholas’s body is giving off holy bone-juice that the public can buy for a tidy profit to the church. Instead, humidity may be causing the liquid. Bari is a port town and the marble tomb is below sea level. The priests may simply be collecting condensation.

Whatever the explanation, all that moisture can’t be good for Nicholas’s remains. In the 2004 documentary The Real Face of Santa, a small camera was inserted into the tomb so that forensic scientist Franco Introna could view inside. He was distressed by what he saw. The bones were lying in pools of shallow water and had deteriorated considerably since the 1950s. He said the bones needed to be treated, or they would be gone within 100 years.

“I am a little bit sad because, of course, this is the last remains of St. Nicholas,” he said, adding again that the bones should be preserved. “These bones don’t belong to Bari. They belong to all the world and to all the people that love St. Nicholas.”