On October 5, 1789, Marie Antoinette dressed in a casual, low-cut dress and a wide-brimmed hat and arranged a campstool on the grassy terrace of her chateau, the Petit Trianon, in Versailles. She was perched there sketching some nearby trees when her quiet repose was interrupted by a breathless page, bringing news that an angry mob was on their way from Paris.

These were the events of the French queen’s last day at her beloved Trianon, and the beginning of the end for the French monarchy. Or at least, these are the details alleged by Charlotte Anne Moberly and Eleanor Jourdain in their book The Adventure. The two women claimed that when they toured the royal palace in 1901, something extraordinary happened: They were transported back to the 18th century, where they glimpsed the queen on what may have been the last happy day of her life.

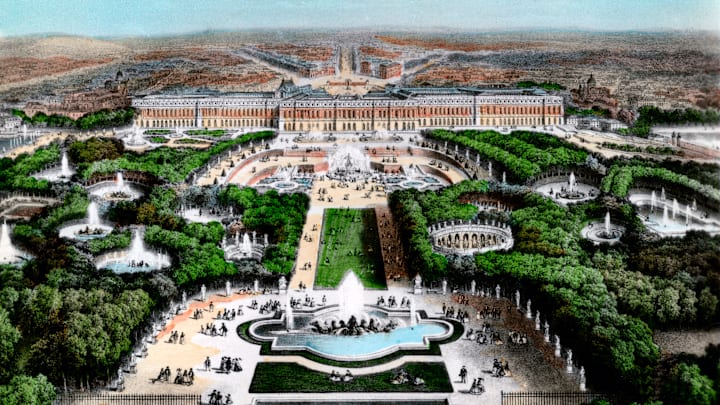

It was a story that Moberly and Jourdain would tell for the rest of their days. Moberly was the well-respected daughter of the Bishop of Salisbury, and the first principal of St. Hugh's College for women in Oxford; Jourdain was slated to be her vice-principal. To get better acquainted, Moberly took a trip to Paris to visit Jourdain, who had an apartment in the city. On August 10, 1901, the two women decided to take a side trip to tour the Palace of Versailles.

After the tour was over, the pair were sitting in the Hall of Mirrors with time to spare when Moberly suggested they see the Petit Trianon. On their way, however, they got lost, and began to feel that something was off. They stopped to ask directions from two men dressed in greenish jackets and tricorn hats, who they assumed to be gardeners because of a wheelbarrow and other tools nearby. Jourdain also saw, to her right, a cottage; in the doorway stood a woman passing a water jug to a young girl, both dressed in unusual clothes. The pair continued toward the Trianon on the men’s directions, but things soon took an eerie turn, as Jourdain later wrote in their book:

"I began to feel as if I were walking in my sleep; the heavy dreaminess was oppressive. At last we came upon a path crossing ours, and saw in front of us a building consisting of some columns roofed in, and set back in the trees. Seated on the steps was a man with a heavy black cloak round his shoulders, and wearing a slouch hat. At that moment the eerie feeling which had begun in the garden culminated in a definite impression of something uncanny and fear-inspiring. The man slowly turned his face, which was marked by smallpox: his complexion was very dark. The expression was very evil and yet unseeing ... I felt a repugnance to going past him."

Just then, another man—speaking in a strange accent—came running up behind them and hurriedly told them the path to take to the Trianon, which led away from the man they feared. After walking on a bit more, they found the chateau at last. On its northside terrace, Moberly observed a pretty woman with fluffy blond hair and a shady hat sketching. "I thought she was a tourist," Moberly later wrote, "but that her dress was old-fashioned and rather unusual ... I looked straight at her; but some indescribable feeling made me turn away annoyed at her being there." Moberly and Jourdain walked up to the terrace and were guided by a boy to the front drive. Then their foray into the past ended.

It would be a week before they spoke to each other of the unusual events of that day. At first, they agreed that the Petit Trianon must be haunted. But they eventually decided these weren't any ordinary apparitions.

Three months after their tour of Versailles, Jourdain was preparing a class lesson on the French Revolution when she learned that on August 10, 1792—109 years to the day before Moberly and Jourdain’s encounter at Petit Trianon—the Tuileries Palace had been besieged and burned by the Paris Commune. The royal family, including the queen, were forced into the Hall of Assembly, where they were taken prisoner three days later. The monarchy would be officially abolished the following month; Marie Antoinette was executed on October 16, 1793. Moberly and Jourdain concluded that what they had actually walked into was a vivid memory the queen had conjured during the burning of the Tuileries in 1792, picturing her last peaceful moments at Petite Trianon.

It would not be until 10 years later, in 1911, that Moberly and Jourdain published The Adventure, under the pseudonyms Elizabeth Morison and Frances Lamont, respectively. The teachers set out to bolster their supernatural claims in true academic fashion by combing through the French National Archives and extensively researching French history. They compared maps of the Versailles grounds from 1789 and 1901, analyzed the clothing, and made several return visits in an attempt to prove that the Versailles they experienced was that of the 18th century, rather than the 20th. They concluded that the two gardeners in green were members of the queen’s Swiss Guard, the scary man was Comte de Vaudreuil (who played a role in betraying the queen), the pretty woman in the shady hat was Marie Antoinette herself, and the running man was the page who informed her of the mob.

The book was widely popular, being reprinted multiple times in its first year, selling 11,000 copies by 1913, and going through five editions. But along with its popularity came much criticism. Some claimed that Moberly and Jourdain’s account was overly embellished and not the work of anything supernatural, pointing to inconsistencies between early accounts the pair had sent to the Society of Psychical Research and the book. Other criticisms of the book and the two women were, however, of a more personal nature. (Their identities as the authors was an open secret, since the women had shared their experiences with family, friends, and colleagues; the third edition also used their real names.) Being two unmarried, childless women past the usual age for matrimony—some sources say they also lived together—raised many eyebrows in the first part of the 20th century, and their lack of conformity to the era's expectation for women fed many alternative theories surrounding the encounter.

Lucille Iremonger, a student at St. Hugh's and a descendant of Comte de Vaudreuil, wrote a scathing and homophobic description of the incident in her 1957 book, The Ghosts of Versailles. She speculated that the two women were romantically involved, and suggested that their tale was in part the result of their "sexual deviancy."

Other writers argue that Moberly and Jourdain did witness something out of the ordinary, but it had nothing to do with ghosts or time slips. In Prince of Aesthetes: Count Robert de Montesquiou, 1855-1921, Philippe Jullian speculated that the women had stumbled onto a historical for a fancy dress party hosted by the dandy poet Robert de Montesquiou and his secretary and lover Gabriel Yturri. The guards were other party goers, the queen was either a woman of Montesquiou’s close circle or a man dressed in drag, and Comte de Vaudreuil could have been Montesquiou himself. The idea was that as two English “spinsters,” Moberly and Jourdain might have been so unfamiliar with such parties that they conjured hallucinations instead of understanding their surroundings.

In other words, Moberly and Jourdain were either so gay that they hallucinated the event or so prudishly straight that they hallucinated it.

Dame Joan Evans, a historian and former student at St. Hugh's, obtained the copyright to The Adventure as Jourdain's literary executor and accepted Jullian’s explanation of the events, suspending printing after the fifth edition in 1955. Moberly and Jourdain, however, never retracted their stories. In 1924, Jourdain became embroiled in a scandal at St. Hugh's after wrongfully firing a tutor; it was clear she would be asked to resign by the college council, but died of heart failure at the age of 61 before they could do so. Moberly died in 1937 at the age of 90, still telling the story of her adventure at Versailles to those who would listen.