Just underneath the surface of many paintings, both famous and obscure, is a hidden painting that could have been. Sometimes, these ghostly images are apparent to the naked eye if you look closely enough. More often, they are revealed by restoration processes, X-rays, and careful investigation by art historians and preservation specialists.

In some cases, scandal forced artists to correct controversial details; in others, the artist simply changed his or her mind. During lean times, some artists resorted to painting over less satisfactory or unfinished work because they could not afford new canvas.

Instances of painterly corrections that expose previous versions of the design are referred to as pentimenti, from an Italian phrase meaning “to repent,” essentially because the artist has “repented” for a choice made earlier in the creative process. A pentimento can be, for example, a change in the position of a hand, the enlargement of a tablecloth, or the reduction of the size of a hat. Small pentimenti are everywhere in paintings, and can be more common among schools of painters who had workshops and assistants. The idiosyncrasies of pentimenti have even been used to identify lost works by great painters such as Leonardo da Vinci (and cause major controversy).

Whatever the circumstances, thousands of paintings contain fascinating omissions, fixes, and shrewd substitutions. Here are just as few.

1. The Fifth Season // Rene Magritte

The Fifth Season (1943) isn’t one of the Belgian Surrealist’s masterpieces—in fact, it’s been called a bad painting. But conservators at the Royal Museums of the Fine Arts of Belgium recently discovered a hidden image underneath the somewhat mundane scene of two men exchanging artworks on a street: a ghostly portrait of a woman, which may be Magritte’s wife, Georgette. Magritte buried his older work under newer compositions at least once before. In 2013, scholars uncovered portions of a 1927 painting called The Enchanted Pose, which had been assumed lost, under a 1935 painting titled The Portrait.

2. Monsieur de Norvins // Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

This 1811-12 portrait of Napoleon’s chief of police in Rome, by the French Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, features a shadowy trace of another face. Floating within the fabric of the lefthand curtain, the features of a completed bust of a child’s head can be seen, even with the naked eye. Art historians have also noticed something haphazard about the inclusion of the bust of Minerva on the right, which is so far out of frame that it seems like an afterthought.

Given the hasty and awkward omission of the figure on the left, it is thought to be a bust of the head of Napoleon’s son, who was dubbed the king of Rome. In 1814, Napoleon lost power, and association with him became—at the very least—unfashionable for a portrait painter. The coverup, which may not have been made by Ingres himself, is thought to have been politically motivated. You can see it for yourself at London’s National Gallery.

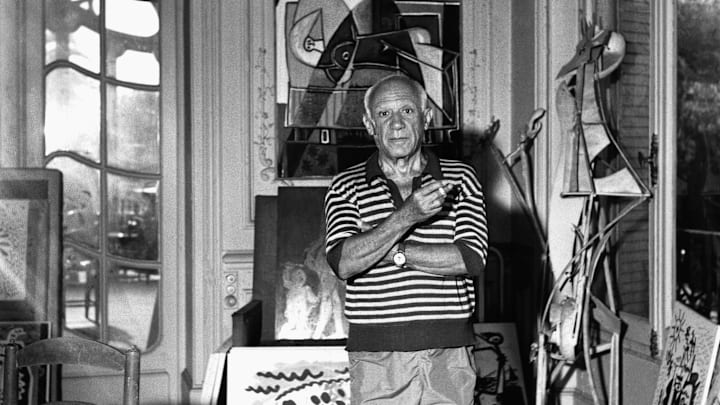

3. The Old Guitarist // Pablo Picasso

During Pablo Picasso’s “Blue Period” (1901-1904), funds for art supplies were tight. Sometimes, when the artist was particularly strapped, he would substitute cardboard for canvas. When he had canvas, it was occasionally repurposed. One of the best-known examples of the body of work Picasso created during this time, The Old Guitarist, turned out to have been painted over the figure of a woman.

When seeing the painting in person at the Art Institute of Chicago, you may notice what looked like another face behind the bent neck of the guitarist. X-ray imaging has revealed that the unidentified woman is nursing a small child, and appears to be in a pastoral setting accompanied by a bull and a sheep.

4. The Blue Room // Pablo Picasso

Picasso’s 1901 Blue Period painting The Blue Room, a masterpiece in the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., has more than its tone in common with The Old Guitarist. Infrared imaging uncovered another portrait underneath the room scene. The bearded man, who is in formal wear and wearing a number of rings on his fingers, reclines pensively when the painting is vertically oriented. Like the woman beneath The Old Guitarist, he probably is another victim of Picasso’s canvas budget.

5. Madame X // John Singer Sargent

Madame X, by the American painter John Singer Sargent, is a familiar work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—and somewhat of a style icon with her simple black dress, statuesque figure, and haughty expression. At the time of its unveiling in the 1880s, this portrait was considered an unflattering, scandalous affront to decency, and it had a disastrous effect on the European career of its creator.

The woman in the portrait is Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, a New Orleans expatriate who was trying to make her mark on the European scene as a great beauty. The pallor of her skin, which is notable in the painting and prompted one contemporary critic to call her “cadaverish,” was achieved by ingesting arsenic wafers. She was known to heighten the effect by rouging her ears and deepening the color of her hair with henna.

Sargent, hoping to capture her at her most dramatic, selected her striking black gown for her to wear. He painted her with one jeweled strap of her gown hanging from her shoulder.

When the portrait was first displayed in a salon exhibition, the strap created an instant outcry. Critics called the costume of the subject “flagrantly insufficient,” and Gautreau’s humiliated family called for it to be taken out of the exhibition. Sargent, in a rare moment of self-doubt, took the painting and fashioned a properly placed strap on the now infamous Madame X’s shoulder.

6. Woman at a Window // Palma Vecchio

At the National Gallery in London, the restoration process of an early 1500s painting of a woman at a window by the Venetian artist Palma Vecchio uncovered a remarkable makeover. What museum workers had thought to be varnish imperfections in the woman’s hair turned out to be the blonde locks of the original figure showing through a subsequently applied layer of paint.

The blonde (seen above in the video) underneath the modest brunette is a far more interesting subject. Her gaze is more calculated, her expression more confusing, and her bosom obviously more detailed. At some point, she was painted over as a humble brunette, with a modest expression and unthreatening cleavage. Today, the painting has been restored to its original state, and the Renaissance woman can be seen clearly again at the National Gallery.

7. View of Scheveningen Sands // Hendrick van Anthonissen

When this 17th-century Dutch painting was donated to Cambridge University’s Fitzwilliam Museum, it appeared to be a simple beach scene. However, the conservator n charge of restoring it before exhibition thought it odd that a large crowd appeared to have congregated by the sea in the distance for no discernible reason.

A little cleaning uncovered a figure, apparently standing on the horizon. More cleaning revealed that the figure was, in fact, standing atop a whale on the shore that had been painstakingly painted over.

The repainting is thought to have occurred during the 18th or 19th centuries. Paintings often served a decorative function, and were as much a part of a well-appointed living room as were chairs and rugs. It is possible that a whale carcass was considered an unsavory image to have in a Dutch drawing room, even though the Netherlands dominated the European whaling industry when the painting was created.

8. Sir John Maitland, 1st Lord Maitland of Thirlestane // Adrian Vanson

A centuries-old portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots was discovered hiding underneath a portrait of Sir John Maitland, former lord chancellor of Scotland. The queen’s image—which had been thought lost for almost 450 years—had been hanging in not-so-plain sight on the wall of a historic London home. According to the Guardian, “her portrait may have been considered dangerous, left unfinished, and then overpainted by the nervous artist, in the political turmoil after she was executed in 1587.” The painting usually hangs at Ham House, a Stuart estate in Surrey, UK.

A version of this story was published in 2017; it has been updated for 2023.