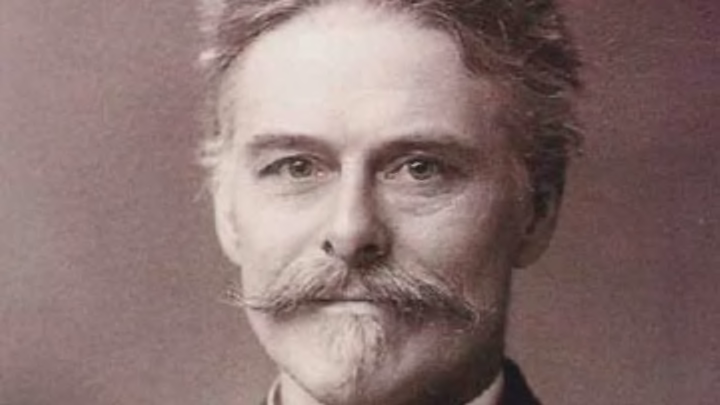

Edward Drinker Cope’s skull started out on his body, naturally enough.

Born into a well-off Quaker family in 1840, the Philadelphia native was already journaling and drawing his observations about the natural world at the age of six. By 19 he’d published his first scientific paper, a treatise on salamanders. Like many scholars of his day, Cope was a generalist, studying amphibians and fish and whatever else caught his eye, but he’s most famous for his work in paleontology and his contentious battle with rival Othniel Charles Marsh.

If you think science is a pure pursuit of truth without respect to ego, you know nothing of the Bone Wars. Cope and Marsh sent collectors digging and blasting their way across the American West in search of dinosaur remains, often naming the same species more than once in an attempt to get the most credit. When their collectors were done excavating a site, they weren’t above destroying the evidence to make sure the next group wouldn’t have any fossils to recover for themselves.

The rivalry began when Marsh embarrassed Cope by showing he’d placed the head of an Elasmosaurus on its short tail instead of its long neck. The two paleontologists fought for years in academic circles and newspapers, and both wound up smeared by the end. Along the way they discovered many dinosaurs you’ll see in museums today, including Triceratops, Stegosaurus, and Apatosaurus.

Elasmosaurus, the dinosaur that started Cope's feud with Marsh.

The Bone Wars have been chronicled in books, documentaries, and even a graphic novel, but the story of Cope’s skull rivals any tale of academic intrigue. Like the head of the Elasmosaurus that started the fossil feud, Cope’s own noggin wandered for a while before winding up back where it belonged. Author David Rains Wallace relates a good part of the tale in The Bonehunters’ Revenge: Dinosaurs, Greed, and the Greatest Scientific Feud of the Gilded Age.

Cope died in 1897, most likely alone on a cot surrounded by fossils. Prior to death he’d arranged for his body to be donated to science, specifying that his skeleton should be prepared and preserved but not placed on exhibition. Originally kept by the American Anthropometric Society, a group with a fondness for measuring the brains of famous men, Cope’s skull was passed in 1966 to the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Anthropology, and that’s when things got a little weird.

A distinguished anthropology professor by the name of Loren Eiseley saw Cope’s name on a box and left a note that said, “Gone to lunch—Edward Drinker Cope.” Eiseley took the bones back to his office and laid them out on a conference table to make sure everything was intact before placing them back into the box. Over the years, the paleontologist's remains became a fixture in Eiseley’s office, and the anthropologist toasted “Eddie” with sherry and even bought him a birthday present of a skeleton-bedecked printing block. The office staff also decorated Cope for Christmas.

Eiseley had a nephew named Jim Hahn, a sailor who studied physical anthropology under his uncle at Penn. The two men looked and sounded a lot alike, and they had little adventures together, one time finding some .356 Magnum shells in a parking lot and ransacking a nearby Salvation Army drop box in search of the gun, according to Fox at the Wood’s Edge, Gale E. Christianson’s biography of Eiseley. So it was not surprising when the professor, after deciding he wanted to be buried with Cope’s bones, picked his nephew to help him with the task.

Eiseley died in July 1977, and Jim Hahn found himself in the professor’s office at the Penn Museum trying to tape Cope’s bones to his own arms and legs. Hahn was sweating in the summer heat and worried he’d fall apart right before the museum guard’s eyes, so he opted instead to carry Cope out in a box with a bunch of his uncle’s books. That went off without a hitch, but at the funeral home Hahn realized there was no way he could get Eddie in the coffin without the mortician noticing, so back to the museum the bones went.

Cope rested in peace until the Jurassic Park mania of the early 1990s, when a photographer named Louie Psihoyos was traveling around the country shooting paleontology artifacts. Psihoyos would later direct The Cove, the 2009 Academy Award-winning documentary about dolphin hunting in Japan, but he was already a successful photographer by the time he found himself talking to paleontologist Ted Daeschler at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. The discussion turned to Cope, and Daeschler mentioned that Eddie’s bones were sitting in a box across town. Daeschler made a call and the museum left Cope at the front desk for Psihoyos, who picked up the two boxes and took Cope on the road.

“The box with the skull was last used for electrical parts,” says Psihoyos, who, along with collaborator John Knoebber, started treating Cope like one of the crew. Knoebber made a velvet-lined mahogany box for the skull, which they didn’t like leaving in the van, so “Do you have Ed?” became a common refrain every time they left a diner.

Cope’s skull was a conversation starter, granting them entrée with paleontologists they interviewed for their book Hunting Dinosaurs. “That was like bringing Elvis to a rock ‘n’ roll convention,” says Psihoyos. “You felt like you knew him, because you’d read a lot of his history.”

But there was a problem: The museum had no idea Psihoyos and Knoebber were taking the skull on the road. “They didn’t return it, and they took it on a trip,” says Daeschler. “Which is just not cool. Granted, they’re not scientists, and they don’t know the ways of loans that come from scientific institutions.”

Psihoyos estimates he had the skull for three years. Near the end, a paleontologist named Bob Bakker (who is famous for helping popularize the theory that some dinosaurs were warm-blooded) declared Cope’s remains as the ideal example of humankind. Every time a new species is classified, one example is declared to be the type specimen. When Carl Linneaus, the father of modern taxonomy, originally named Homo sapiens in 1758, he skipped that part and said, “Know thyself.” Bakker went ahead and basically tried to change that to “Know Edward Drinker Cope.”

“The legend I heard was that Cope wanted to be the type specimen,” says Psihoyos. “This is the dark part of the history. Cope was part of a group of scientists back then who were trying to set forth the idea that the Caucasian race is superior, and they were using brain case size and all these notions to legitimize it. Well, that never came to fruition.”

Today’s historians and paleontologists don’t deny that Cope, like many of his contemporaries, held some very racist ideas about human anatomy, but what’s much less clear is whether Cope wanted to become the type specimen when he donated his body to science. As Wallace explains in The Bonehunters’ Revenge, Cope had few teeth at the end of his life, and some of Cope and Marsh’s biggest contributions to science dealt with dentition, so the Philadelphia Quaker would’ve known he wasn’t suitable. But the legend persists, probably because it would’ve been one final way for Cope to best his rival.

Drawing by artist Charles R. Knight of two Lealaps fighting. It's considered to be symbolic of Cope and Marsh's feud.

“Cope didn’t want people to do what Psihoyos did,” says Daeschler. “He did not want to be paraded around because he was the great Professor Cope. He had a high opinion of himself, so he thought that might happen. And it did. It absolutely did happen.”

The Penn Museum demanded Cope back, and they added another wrinkle to the story: Professor Eiseley had loaned the skull to an artist from the Museum of Natural History in the 1970s, and they weren’t even sure if the right one ever came back. So maybe Psihoyos, Knoebber, and Bakker had been hanging out with the wrong skull all along.

“They were embarrassed to have rented him out like a library book,” says Psihoyos, who shipped the remains back via FedEx. “I’m convinced it was Ed.”

That’s one part of the story where the Penn Museum now agrees with the photographer. The skull, whose jaw went missing long before Psihoyos’ journey, has been compared to older drawings of Cope’s remains and determined to be the real deal. Cope is not the type specimen, however. The academic community gives that honor to Linneaus.

Cope’s skull is back under the care of the Penn Museum, in that fancy velvet-lined box. Janet Monge, associate director at the museum, says she sometimes brings Cope out for classes on the type-specimen controversy, but as for his current whereabouts:

“He’s on the shelf right now.”

All photos courtesy Wikimedia Commons.