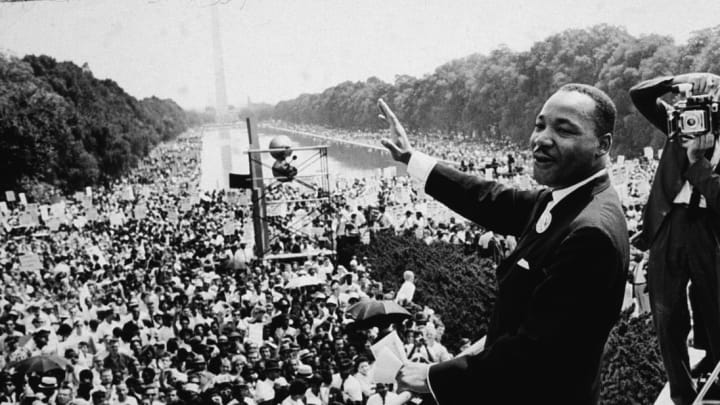

On August 28, 1963, under a sweltering sun, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators gathered by the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. to participate in an event formally known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. From start to finish, it was a passionate plea for civil rights reform, and one speech in particular captured the ethos of the moment. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s 17-minute “I Have a Dream” address—which was broadcast in real time by TV networks and radio stations—was an oratorical masterpiece. Here are some facts about the inspired remarks that changed King's life, his movement, and the nation at large.

1. Martin Luther King, Jr. was the tenth orator to take the podium that day.

Organizers hoped the March would draw a crowd of about 100,000 people; more than twice as many showed up. There at the Lincoln Memorial, 10 civil rights activists were scheduled to give speeches—to be punctuated by hymns, prayers, pledges, benedictions, and choir performances.

King was the lineup’s tenth and final speaker. The list of orators also included labor icon A. Philip Randolph and 23-year-old John Lewis, who was then the national chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. (He’s now a U.S. congressman representing Georgia’s fifth district.)

2. Nelson Rockefeller inspired part of the "I Have A Dream" speech.

For years, Clarence B. Jones was Dr. King’s personal attorney, a trusted advisor, and one of his speechwriters. He also became a frequent intermediary between King and Stanley Levison, a progressive white lawyer who had drawn FBI scrutiny. In mid-August 1963, King asked Jones and Levison to prepare a draft of his upcoming March on Washington address.

“A conversation that I’d had [four months earlier] with then-New York governor Nelson Rockefeller inspired an opening analogy: African Americans marching to Washington to redeem a promissory note or a check for justice,” Jones recalled in 2011. “From there, a proposed draft took shape.”

3. The phrase “I have a dream” wasn’t in Martin Luther King, Jr.’s prepared speech.

On the eve of his big speech, King solicited last-minute input from union organizers, religious leaders, and other activists in the lobby of Washington, D.C.’s Willard Hotel. But when he finally faced the crowd at the Lincoln Memorial, the reverend went off-book. At first King more or less stuck to his notes, reciting the final written version of his address.

Then a voice rang out behind him. Seated nearby was gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, who yelled, “Tell ‘em about the dream, Martin!” Earlier in his career, King had spoken at length about his “dreams” of racial harmony. By mid-1963, he’d used the phrase “I have a dream” so often that confidants worried it was making him sound repetitive.

Jackson clearly didn't agree. At her urging, King put down his notes and delivered the words that solidified his legacy:

“I say to you today, my friends, that in spite of the difficulties and frustrations of the moment, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream ... I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character."

King's friends were stunned. None of these lines had made it into the printed statement King brought to the podium. “In front of all those people, cameras, and microphones, Martin winged it,” Jones would later say. “But then, no one I’ve ever met could improvise better.”

4. Sidney Poitier heard the "I Have A Dream" speech in person.

Sidney Poitier, who was born in the Bahamas on February 20, 1927, broke Hollywood's glass ceiling at the 1964 Academy Awards when he became the first African American to win the Best Actor Oscar for his performance in Lilies of the Field (and the only one until Denzel Washington won for Training Day nearly 40 years later). Poitier, a firm believer in civil rights, attended the ’63 March on Washington along with such other movie stars as Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston, and Paul Newman.

5. The "I Have A Dream" speech caught the FBI’s attention.

The FBI had had been wary of King since the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover was perturbed by the reverend’s association with Stanley Levison, who’d been a financial manager for the Communist party in America. King's “I Have a Dream” speech only worsened the FBI’s outlook on the civil rights leader.

In a memo written just two days after the speech, domestic intelligence chief William Sullivan said, “We must mark [King] now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro, and national security.” Before the year was out, attorney general Robert F. Kennedy gave the FBI permission to wiretap King’s telephone conversations.

6. In 1999, scholars named "I Have a Dream" the best American speech of the 20th century.

All these years later, “I Have a Dream” remains an international rallying cry for peace. (Signs bearing that timeless message appeared at the Tiananmen Square protests). When communications professors at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Texas A&M used input from 137 scholars to create a list of the 100 greatest American speeches given in the 20th century, King’s magnum opus claimed the number one spot—beating out the first inaugural addresses of John F. Kennedy and Franklin Roosevelt, among others.

7. A basketball Hall of Famer owns the original copy of the "I Have a Dream" speech.

George Raveling, an African-American athlete and D.C. native, played college hoops for the Villanova Wildcats from 1956 through 1960. Three years after his graduation, he attended the March on Washington. He and a friend volunteered to join the event’s security detail, which is how Raveling ended up standing just a few yards away from Martin Luther King Jr. during his “I Have a Dream” address. Once the speech ended, Raveling approached the podium and noticed that the three-page script was in the Reverend’s hand. “Dr. King, can I have that copy?,” he asked. Raveling's request was granted.

Raveling went on to coach the Washington State Cougars, Iowa Hawkeyes, and University of Southern California Trojans. In 2015, he was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. Although a collector once offered him $3 million for Dr. King’s famous document, Raveling’s refused to part with it.