As a girl, Alaqai Beki mastered horseback riding and archery, the skills expected of a Mongol woman during the 12th and 13th centuries. By her teens, she was skilled enough to follow her father into battle, but as the ruler of an allied nation, she played an even larger role in his success, providing troops and strategic support for his campaign of military conquests.

Her father was Genghis (Chinggis) Khan, a man history does not remember primarily for his progressive views. Yet, according to The Secret History of the Mongols, the oldest surviving literary work in the Mongolian language, he believed women were more than capable of ruling.

“In Mongol society, women managed the homeland, including trade and finances, while men went out herding, hunting, or raiding,” Jack Weatherford, author of The Secret History of the Mongol Queens, tells Mental Floss. “As the empire grew, the responsibility of the women grew.”

A Division of Labor

With an army of around 100,000 in a nation of about a million, Khan could not afford to leave men behind to guard each conquered or allied nation, so he placed both his daughters and sons on their thrones. His daughters ruled nations that controlled the Silk Road, the favored route for trading spices, cloth, pottery, and other goods between China, India, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. “The daughters and daughters-in-law were better educated and capable of managing them,” Weatherford tells Mental Floss.

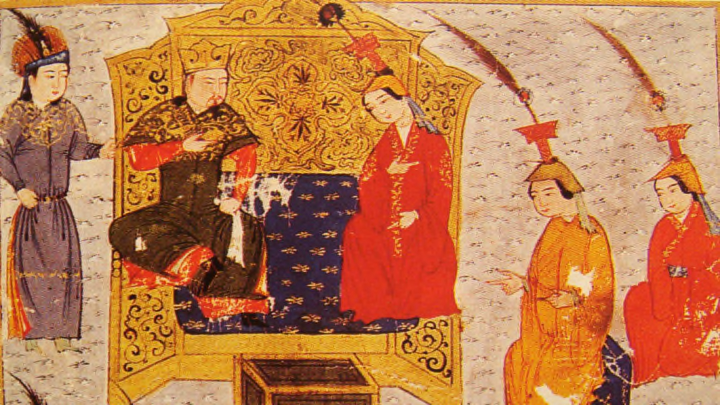

Whenever one of his daughters married, Genghis Khan decreed his daughter would rule the nation and declared her husband a prince consort. The prince had to divorce all previous wives. “The husband had to join Genghis Khan and fight with him and his army,” Weatherford says. “He had to bring with him his army also. This minimized any resistance to his daughters in their new homeland.”

Still, Anne F. Broadbridge, author of Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire, cautions against ascribing feminist ideas to Khan. “Nomadic society at the time had a division of labor,” she tells Mental Floss. “Women did certain tasks; men did others. Neither could function without the other, so it was a team effort. I think he liked his womenfolk, and he wanted to provide for them (part of a man’s job), but he also saw them as an active, necessary part of the system of everyday life.”

A Model for the Mongol Empire

Alaqai Beki was only 16 when she married into the Onggut Nation, but her father ensured her complete authority. When she was 20, assassins killed her husband during a rebellion against her rule. She fled home, along with two of her stepsons, only to return alongside her father and subdue the rebellion. In retaliation, her father wanted to kill every Onggut man, but Alaqai persuaded him to punish only the assassins.

This intervention earned her the nation’s loyalty—a loyalty that was required to conquer China. To secure her throne, she married her stepson Jingue and had a son. After Jingue died, she married her other stepson, Boyaohe. “Alaqai married into the royal family of the Ongguts, who lived on the border with the Jin empire of China and guarded it for the Jin,” Broadbridge says.

Under Alaqai’s rule, the Ongguts no longer protected the Jin. During Khan’s 1211–1215 and 1217–23 campaigns against the Jin Empire, Alaqai supplied her father’s troops with food, the horses she bred, and a strategic base. In exchange, he also gave her newly conquered territory in China to rule.

Alaqai taught herself to read, eagerly consuming works of religion and medicine. She organized medical facilities throughout her realm, recruiting healers from China. She dispatched medical personnel to accompany troops for her father’s campaign, thereby introducing Chinese medicine to the Muslim and Western worlds.

The system of government she devised for the Onggut nation—based on traditional Mongol practices—eventually became the model for most of the Mongol Empire. The empire’s laws favored ending aristocratic privilege [PDF]. Anyone could apply for a civil service position. Taxes were abolished for doctors, priests, teachers, and schools, promoting health and literacy. Torture was outlawed, and criminals could be forgiven offenses, if they sincerely repented. Businesses could declare bankruptcy. Religious freedom existed for all.

Alaqai, and sisters Quojin, Tumelun, Al Altun, and Checheyigen, the daughters of Khan’s senior wife, Borte, were well-trained in trade and finances. These skills helped their kingdoms—from Eastern Iran to Western Mongolia—thrive and revamped the trade routes between them.

To facilitate the flow of goods through the Silk Road’s arduous deserts and mountains, water sources were diverted to create regular oases. The oases featured resting stations, relief animals, a postal service, and even low-cost loans, available to all merchants, regardless of nationality or religion. The sisters also developed a system of investment—funding and profiting from—the trade of furs from Siberia, silk from China, and wines from the Uighur nation.

Alaqai ruled until her death in 1230, without another rebellion. After her father died, power struggles splintered the empire and the sister-queens’ contributions were mostly erased from history.