In 130 CE, a handsome Greek youth drowned in the Nile.

Born about 110 CE in Bithynia, in modern Turkey, Antinous’s early years are mostly a mystery. As a teenager, he met the Roman emperor Hadrian when he toured the provinces of his empire. The leader saw promise in Antinous and sent him to be educated in the capital. By the time Antinous was about 18, and Hadrian was in his early fifties, the pair were inseparable.

Romantic relationships between younger and older men had been socially accepted in ancient Greece. In the Roman era, such relationships were less fashionable, but powerful men continued to have open affairs with both men and women. Hadrian traveled across the Roman territories with his young lover, and they even appeared in sculpted reliefs together. It was on one of Hadrian’s tours in Egypt that Antinous met his death in the Nile under murky circumstances. Theories were put forward at the time as to how the tragedy occurred: suicide, murder, or ritual sacrifice.

Antinous’s earthly existence ended that night—but he would go on to have one of the most remarkable afterlives in history.

The Cult of Antinous

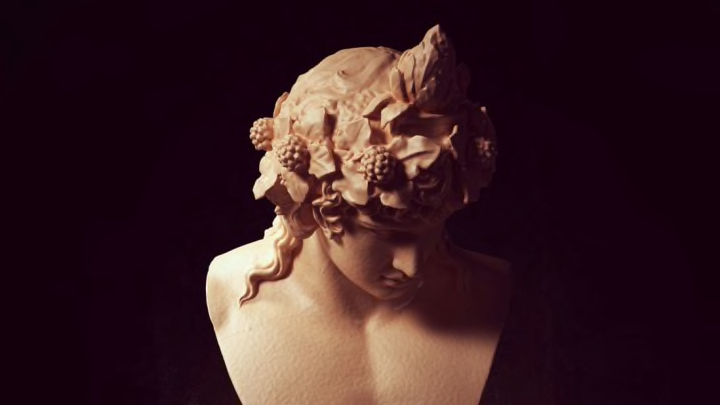

In the immediate aftermath of Antinous’s death, Hadrian was overcome with grief. He ordered that a new city, Antinoöpolis, be built on the spot where Antinous died. Hadrian sanctioned a religious cult to worship the youth as a god and ordered statues made of the new deity in abundance. To thoroughly incorporate Antinous into Rome’s pantheistic religion, some statues showed him in the guise of other deities, such as Dionysus, Osiris, and Sylvanus.

While the cult of Antinous seems to have died out soon after the death of Hadrian himself in 138 CE, it was harder to destroy the youth’s image. Hundreds of statues, cameos, and coins all bore his face and mass of unruly curls. Thanks to Hadrian’s devotion, Antinous remained one of the most recognizable personae from antiquity. And more than a thousand years after he drowned, he inspired a new generation of admirers.

In the Renaissance, gay men rediscovered Antinous’s beauty and tragic story. The god gave legitimacy to their desires while the legal system forbade them to act on their feelings.

Since at least the 8th century in Europe, the church had handed down penances for those caught performing “unnatural acts.” Legal punishments were codified in England in 1533 by the Buggery Act of Henry VIII. This law moved cases involving homosexual acts from ecclesiastical courts to the state courts. For the first time, those convicted of such acts could be put to death. (The last men to be executed under this law were hanged in 1835.) The persecution forced gay men to express themselves in code.

From Statue to Symbol

Johann Winckelmann, the most influential art critic of the 18th century, reintroduced the story of Antinous to post-Enlightenment Europe. His widely read studies of Greek and Roman art presented new interpretations of the ancient world. For Winckelmann, the pinnacle of these treasures of antiquity were the statues of Antinous, which he described as “the glory and crown of art in this age as well as all others.” About a large sculpted head of the youth called the Antinous Mondragone (now in the Louvre), Winckelmann wrote, “it is the most beautiful work that has come down to us.” When he had his own portrait painted, Winckelmann—who had romantic relationships with younger men—was shown with an engraving of Antinous in front of him. The image could move even heterosexual critics: Edward Gibbon described it as “soft, well-turned, and full of flesh.”

Around the same time, well-to-do Britons began embarking on the Grand Tour—lengthy jaunts through European capitals to absorb culture and broaden their horizons. Rome was a must-see stop on the circuit, and many in Britain feared that young men who went off on the Grand Tour might be lured by the vices on the continent. A 1731 pamphlet even described Italy as "the Mother and Nurse of Sodomy." Like modern students on spring break, young people could satisfy their desires far from parents and the law.

Bringing antique statues of Antinous (or replicas of the originals) back to Britain was a way for gay men to remember the freedom and liberties they experienced on their tours. A nobleman, displaying an Antinous in his stately home, could show off his taste and knowledge of the Classics, and perhaps drop a hint about his sexual inclinations.

An 1861 British law did away with the death penalty for homosexual acts but made them punishable by a minimum of 10 years in prison. Victorian poets and writers began using Antinous as a code word for love between men, shielding their explorations of the forbidden concept from censorious eyes.

Victorian Vices

In 19th-century England, one of the first literary critics to dare write of Antinous’s implicit symbolism was John Addington Symonds. Though married, Symonds had affairs with men and wrote poems and studies celebrating the love that dare not speak its name. In his 1878 poem, “The Lotos-Garland of Antinous,” he wrote:

“But Adrian dreaming lay, and at his side Antinous with large eyes blank and wide Lay dreaming. Thus adown the sleepy tide, As in a trance toward Lethe through still air, Lost to the joy of living did they fare.”

The poem ends with Antinous offering himself to the Nile in exchange for ensuring the health of the Roman emperor, romanticizing the youth’s untimely death from drowning: “I give my life for Adrian’s! Wherefore should I live?” Symonds argued that love between men rose to the plane of heroism.

Other gay writers were not as overt as Symonds but used Antinous as code for same-sex desire, knowing that gay readers would pick up on the subtext and prudish types would be none the wiser.

In Oscar Wilde’s decadent novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), the title character embodies the late 19th-century tension between sexuality and morality. His friend, painter Basil Hallward, becomes infatuated with Dorian’s good looks. He tells his bad-influence friend, Lord Henry Wotton, that Dorian’s face is a world-shaking moment:

“I sometimes think, Harry, that there are only two eras of any importance in the world's history. The first is the appearance of a new medium for art, and the second is the appearance of a new personality for art also. What the invention of oil painting was to the Venetians, the face of Antinous was to late Greek sculpture, and the face of Dorian Gray will some day be to me.”

Wilde returned to the image of Antinous in his poem “The Sphinx” (1894), imagining what the Egyptian monument saw in its long life:

“Sing to me of that odorous green eve when crouching by the marge You heard from Adrian's gilded barge the laughter of Antinous And lapped the stream and fed your drouth and watched with hot and hungry stare The ivory body of that rare young slave with his pomegranate mouth!”

Unfortunately, Wilde’s praise of the relationship between Hadrian and Antinous would become part of the legal case against him in 1895. Wilde’s romantic affair with the younger Alfred Douglas eventually led to his criminal prosecution for “gross indecency”—another, less appealing code word for homosexuality. Wilde’s conviction and sentence to hard labor cast a chill over the gay literary scene in Victorian London, breaking the code of Antinous.