The old Wild West is the stuff of legends: Gunslingers robbing banks and trains. Cowboys on long cattle drives. Gold and silver rushes.

Dinosaurs, UFOs, feral camels, and giant cannibals probably don’t come to mind.

But every time period has its strange stories, and the Wild West is no different. Some of those stories are exactly what you’d expect, while others are surprisingly modern.

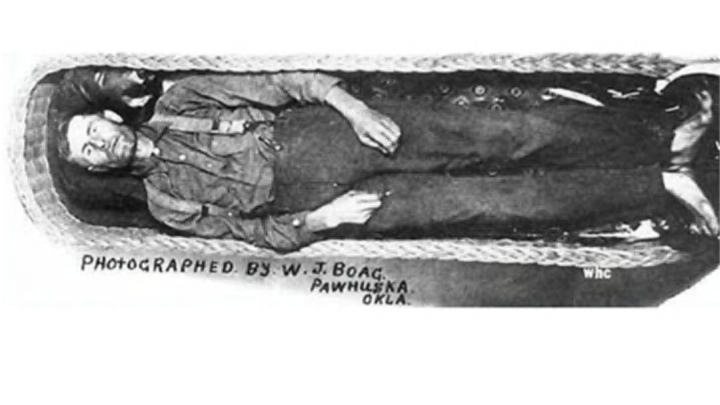

1. ELMER MCCURDY’S AFTERLIFE WAS STRANGER THAN HIS LIFE AS AN OUTLAW.

Elmer McCurdy is not exactly a household name. Unlike Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Jesse and Frank James, or Billy the Kid, his exploits as a train and bank robber never gained him much infamy. Neither did his status as one of the last real Wild West outlaws, killed in a shootout with the law. (He’d never be taken alive, he said.)

No, Elmer McCurdy gained his fame more than 60 years after his death, in 1976, when memories of those wild days on the frontier were dying with the last people who’d lived them.

That’s when the crew of The Six Million Dollar Man borrowed an amusement park funhouse to shoot an episode. As one of the crew members moved a dummy, its arm fell off—revealing that the dummy was actually a mummy. McCurdy, specifically, as an autopsy later revealed.

It seems that after being shot, someone had gone to the funeral home and identified themselves as McCurdy’s long-lost brother in order to take the body. In fact, he was a carnival owner. (Carnivals did a brisk trade in outlaw corpses to attract crowds in the early days of the 20th century.) McCurdy's body also spent time as repayment for a bad debt, playing a mummy in a freak show, and collecting dust in a wax museum storage space before he became a funhouse prop.

McCurdy was finally laid to rest on Boot Hill in Guthrie, Oklahoma, 66 years after he was killed. Were it not for a clumsy prop crew member, who knows where he'd be today.

2. SMALL TOWNS IN CALIFORNIA AND TEXAS REPORTED CLOSE ENCOUNTERS 50 YEARS BEFORE ROSWELL.

Col. H.G. Shaw, as caricatured in the San Francisco Call, Wikimedia Commons// Public Domain

Ask many people about the first major modern UFO incident, and they’ll think back to Roswell, New Mexico. In July of 1947, an Army Air Forces press release reported that airmen had collected a “flying disk” that fell from the sky. It was later reported to be a weather balloon (and even later a nuclear spying apparatus), but by then the concept of flying saucers and government conspiracy theories were well-entrenched in the American imagination.

Except Roswell wasn’t the first UFO incident in U.S. history. Not by a long shot. Turns out, “Cowboys vs. Aliens” has its roots in Wild West pop culture.

Long before close encounters with off-planet visitors offered relief from the tensions of the Cold War, two men from Lodi, California reported an attempted abduction by three alien strangers in 1896. That year, Col. H.G. Shaw and Camille Spooner were traveling from the small town of Lodi to the Fresno Citrus Fair when, they said, they came across three beings that were, well, not human. They were reportedly seven feet tall and very slender.

According to Shaw, the aliens tried to abduct the two men, but Shaw and Spooner were much too heavy to kidnap. Their attempt was foiled, and the three beings leapt back into their spaceship and left.

“I have a theory, which of course, is only a theory, that those we beheld were inhabitants of Mars, who have been sent to the earth for the purpose of securing one of its inhabitants,” Shaw wrote in an account he published in the Evening Mail, a Stockton newspaper at the time.

Lodi resident John Callahan, who is writing a book about the encounter, has tracked down later incidents of UFO sightings in the area. He shares some of his research, including the original news story by Col. Shaw, at the Callahan UFO Report.

A year later, Texas residents reported a strange sight: Cigar-shaped airships (oddly similar to Col. Shaw’s description of the craft in Lodi) flying over the state. Then, one of these crafts crash-landed outside Aurora, Texas. According to a story published in 1979, the townspeople went to the site of the crash and found the body of the pilot, which was “not of this world.” Being good neighbors, they gave the being a proper burial.

In 1973, Mary Evans, who lived in Aurora at the time of the crash, shared her memories with a reporter. “That crash certainly caused a lot of excitement,” she said. “Many people were frightened. They didn’t know what to expect. That was years before we had any regular airplanes or other kind of airships.”

While Evans was not allowed by her parents to go to the crash site, they told her about the alien pilot who was found and its burial. In the same story, one physics professor shared that iron had been found near the purported crash site—iron that did not display the usual magnetic properties of the metal.

Did either story really involve aliens? Probably not. UFO fans have been searching for the alien gravesite in Aurora for decades now with no luck—though they have not been permitted to exhume what they believe is a likely grave, either. The tales may show nothing more than that cowboys believed in alien encounters, too. Or that the thirst for adventure that took many to the Wild West was directed outward, to the skies, as cities grew.

3. TWO TOMBSTONE COWBOYS SHARED ONE HECK OF A HUNTING STORY.

Library of Congress // Public Domain

Dig deep enough in the western United States, and you have a decent chance of finding a fossil. From ichthyosaurs in Nevada to an apatosaurus in Colorado, relics from earlier epochs dot the West.

They’re long dead, though. The creature two cowboys claimed to have bagged near Tombstone, Arizona in April 1890 was reportedly very much alive before they met it.

According to the story that ran in the Tombstone Epitaph back then, “A winged monster, resembling a huge alligator with an extremely elongated tail and an immense pair of wings, was found on the desert between the Whetstone and Huachuca mountains last Sunday by two ranchers who were returning home from the Huachucas.”

After a chase, they shot the bird down, and reported that it was about 92 feet long and and 160 feet from wingtip to wingtip. “The monster had only two feet, these being situated a short distance in front of where the wings were joined to the body. The head, as near as they could judge, was about eight feet long, the jaws being thickly set with strong, sharp teeth. Its eyes were as large as a dinner plate and protruded about halfway from the head,” the Tombstone Epitaph reported.

A photo of the supposed thunderbird, which resembled a prehistoric pterodactyl, was also taken. Or was it?

The story was likely a hoax, and the photo was almost certainly fake. While there are claims the photo was printed with the original article, it was not; the first mention of it appears in 1963. The story itself was never printed by the Epitaph’s competition in Tombstone, and the 1890s was the golden age of yellow journalism in the United States.

But as hoaxes go, it’s a pretty good one, considering all of the thunderbirds, winged serpents, and other strange flying creatures that are found throughout the myths of the Southwest.

4. THE RED GHOST TERRORIZED RANCHERS OF THE SOUTHWEST.

Larry D. Moore via WikimediaCommons //CC BY-SA 4.0

If not for the Civil War and a Washington lobbying group, the Wild West might have been populated by camelboys instead of cowboys. When Edward Fitzgerald Beale, a Texan war veteran, saw how poorly horses fared in the deserts of the Southwest, he suggested importing camels.

It was in 1855 that the idea first took off, under then-Secretary of War Jefferson Davis. Two years later, the U.S. military imported 75 camels and formed a U.S. Army Camel Corps. One group was stationed in Texas, and the other headed for California under Beale’s command.

But with the Civil War looming on the horizon, U.S. Congress was not inclined to pay for still more camels. Mule breeders fought the idea, too. And when the fighting broke out, Confederate forces captured the Texas herd and let most of the camels loose.

That’s where things get interesting, because it turns out Beale and Davis were right. The camels really were exceptionally suited to the desert. And most cowboys had never seen the beasts, meaning that as they roamed Arizona and New Mexico until the late 1890s, they spawned a lot of strange tales.

Take, for example, the Red Ghost. Settlers described it as a terrifying beast with some terrifying rider strapped to its back. According to a Smithsonian article, legend said the ghost took down a bear and could disappear into thin air. But when the Red Ghost was finally caught, it was not by a hardy cowhand who tracked it through the desert, but by a rancher who shot the beast in his tomato patch. That’s when they discovered that the Red Ghost was just a mean, reddish feral camel and a lot of tall tales.

All of the camels were eventually captured or killed, and the last feral camel, Topsy, died in a Los Angeles zoo in 1934.

5. THE WEST IS CHOCK FULL OF MISSING MINES.

The supposed location of the "Lost Dutchman Mine" by Alan English via Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 2.0

With so much gold, silver, and copper in the Wild West, it's no wonder there are so many tales of lost treasure troves throughout the western half of the country. There are dozens of such rumored troves, including the San Saba Gold Mine, the Wheelbarrow Mine, and some that don’t even have a name. There are whole lists of these spots located throughout the United States, but especially in the Old West.

The most famous of these is probably the Lost Dutchman Mine. According to the legend, Jacob Waltz was a German prospector who searched for gold all over the United States, and he found it in Arizona’s Superstition Mountains.

“Near those mountains is the richest gold mine in the world,” he reportedly told his friends. But he died before he could tell any of them the precise location.

Since then, the mine has become legendary. People spend their vacations searching for the Lost Dutchman. Sales of maps purporting to lead to the mine were once bustling. False discoveries have been made.

But the Lost Dutchman and the other missing mines have never been found. It’s possible most of them never existed. But if those that did are ever found, somebody is going to make a lot of money.

6. SOME BELIEVE RED-HAIRED, CANNIBAL GIANTS ONCE ROAMED NEVADA.

Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins. Image credit: Wikimedia // Public Domain

According to the Northern Paiute people, red-haired cannibals once menaced Nevada. Sarah Winnemucca tells the story in her 1883 book about her people's folklore and culture, Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims: “Among the traditions of our people is one of a small tribe of barbarians who used to live along the Humboldt River. It was many hundred years ago. They used to waylay my people and kill and eat them.” The Paiute, she went on to explain, spent three years fighting the “barbarians” before cornering them in a cave, filling the cave with branches, and setting it on fire. They pleaded with the red-haired people to give up eating flesh, but got no answer, and burned the barbarians to death.

The Paiute story sounds like a folk tale, and most likely is. But white settlers heading into Nevada weren’t so sure—nor were they beyond adding their own details to the story. For example, in her account, Hopkins never calls the cannibals giants. That aspect came later, added to the legend sometime between her book in 1883 and the discovery of human remains by guano miners in a cave in Lovelock, Nevada in 1911.

Many of the artifacts recovered by the miners during that excavation disappeared, which may be how legends that the miners found the skeletons of giants sprung up. While no giant remains have ever reappeared, that hasn’t stopped the rumors that the red-haired cannibals were real. Even respected newspapers like the Los Angeles Times have reprinted the story that the miners found 7-foot mummies as fact.

7. THE BODIE CURSE HAS TOURISTS TREMBLING AFTER THEY TAKE HOME ARTIFACTS.

Chris Feichtner, Flickr // CC BY-NC 2.0

Collecting souvenirs is a traditional part of traveling. Every good tourist spot offers plenty of tchotchkes for tourists to take home, either to remember their own trip or to share it with those who couldn’t come along.

But some tourists don’t want to settle for the T-shirts and trinkets in the gift shop. Visitors have been stealing bits of Arizona's Petrified Forest National Park for decades. In February of this year alone, a heavy ore car was stolen from Joshua Tree National Park and the Ahwahnee Hotel sign was stolen from Yosemite.

Bodie State Historic Park—the site of the Wild West ghost town of Bodie—is no exception. The mining town on the border of California and Nevada was founded in 1877 and abandoned in the 1940s, when mining in the region dried up. The state of California took it over and turned it into a park in 1962—and tourists have been stealing artifacts ever since.

But here’s where Bodie differs from other parks plagued by pilfering: Many of the artifacts taken from the town are later returned. Rangers at the park regularly receive letters from people who claim to have stolen an item, only to have their luck turn sour. Tourists who have taken historical items report that their luck went sharply downhill after the thefts. They attributed car accidents, unemployment, chronic illness, and more to the Bodie Curse. (There's even a book called Bad Luck, Hot Rocks collecting these letters.)

In 1996, rangers reported people driving from as far as San Francisco, a six-hour trip, to return items to the exact place they were taken from. One visitor even stopped to return a nail that punctured her tire as she drove through the town.

No one seems to know what’s behind the curse, but many believe that Bodie puts the “ghost” in ghost town. Visitors to the town have reported seeing strange lights and hearing spectral music. One ranger said he’d never seen, heard, or smelled any of the strange things others do, but that he does get a strange feeling when working on the buildings.

Is Bodie really haunted or cursed? Logic says no—but logic also says it’s probably best not to steal anything when visiting the old mining town.