Over the centuries, yuletide revelers have enjoyed far different culinary fare than we do today. Here are seven Christmas dishes of yesteryear that are sure to confuse—or tantalize—your taste buds.

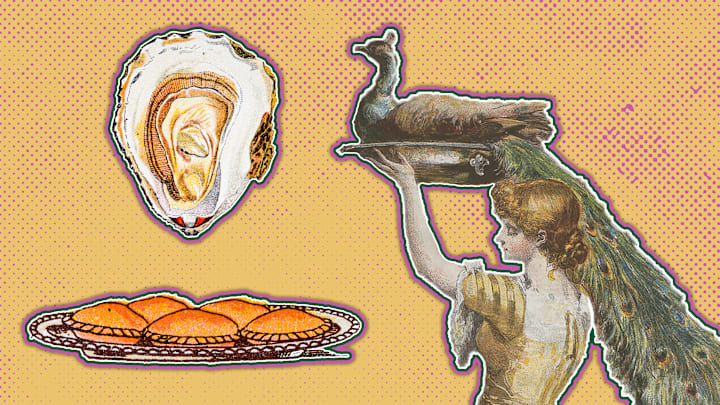

Peacock

During the Medieval ages, some wealthy Europeans dined on peacock at Christmas dinner. The colorful, plumed bird was often baked into a pie, or roasted with its head and tail still intact. Adding to the flamboyant display, the peacock’s feathers were reattached (or the skinned bird was placed back inside its intact skin), and its tail feathers were fully fanned out.

Peacocks likely looked impressive on a banquet table, but the meat reportedly tasted terrible. “It was tough and coarse, and was criticized by physicians for being difficult to digest and for generating bad humors,” author Melitta Weiss Adamson writes in her book Food in Medieval Times. “To make the meat more easily digestible, it was recommended to hang the slaughtered bird overnight by its neck and weigh down the legs with stones.”

In addition to peacock, swans and geese were also on the Christmas menu. But by the 1520s, another roast delicacy—turkey—had been introduced to Great Britain. Explorer William Strickland is credited with bringing the turkey from the New World to England, and King Henry VIII was reportedly one of the first people to enjoy the new bird for Christmas dinner. Edward VII is said to have made the meal trendy.

You May Also Like ...

- 6 Ways Christmases Past Used to be Terrible

- The Ultimate Christmas Trivia Roundup

- 9 Olde-Timey Holiday Drinks to Whip Up This Winter

Add Mental Floss as a preferred news source!

Boar’s Head

In Medieval and Tudor England, wealthy parties celebrated Christmas by feasting on boar’s head. The boar’s head “formed the centrepiece of the Christmas Day meal,” writes Alison Sim, author of Food and Feast in Tudor England (as quoted by the Food Timeline). “It was garnished with rosemary and bay and evidently was presented to the diners with some style, as told by the many boar’s head carols which still exist.”

One English Christmas carol, dating back to the 15th century, is actually called the “Boar’s Head Carol.” Its lyrics include lines like “The boar’s head, as I understand/Is the rarest dish in all this land/Which thus bedecked with a gay garland/Let us servire cantico (serve with a song).” You can listen to a version here.

Oyster Stew

Today, oysters are a delicacy, but for early Americans who settled along the East Coast, they were a plentiful and nutritious food source. People enjoyed them in stuffing, roasts, and chowder—and 19th-century Irish-American immigrants used them to make a traditional Christmas Eve stew.

Most of these Irish transplants were Catholic, and their religious traditions required them to skip the meat on Christmas Eve. Instead, they enjoyed a soup made from dried ling cod—a common fish back in the Old Country—milk, butter, and pepper. But since Irish Americans couldn’t find dried ling cod in America, they substituted it with fresh, canned, pickled, or dried oysters.

Mincemeat Pies

Historians trace mincemeat pie (also called mince pie) back to the 11th century, when Crusaders returned from faraway lands with spices. These spices worked as a preservative, so they were baked into pies containing finely chopped meat, dried fruits, and other ingredients.

Mincemeat pies eventually became associated with Christmas. Bakers added three spices to their pies—cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg—to represent the three gifts the Magi gave the baby Jesus. The pies were also baked into the shape of Jesus’s manger, and a model of the Christ Child was placed on top. People believed that eating a mincemeat pie on each of the 12 Days of Christmas (December 25 to January 6) would bring them good luck.

Over the centuries, the pies grew smaller and rounder, and their filling became less meat heavy, containing ingredients including suet, spices, and dried and brandied fruit.

Sugar Plums

As a child, you might have been inspired by one of ballet's most famous movements—The Nutcracker’s “Dance Of The Sugarplum Fairy”—to wonder what a “sugarplum” actually is. The answer? A hard candy.

Between the 17th and 19th centuries, the term sugarplum was interchangeable with the words dragee or comfit. All referred to a hard, sugary layered candy. Often, the candy contained caraway, cardamom, fennel, ginger, cinnamon, walnut, aniseed, and almond cores. It took time, skill, and special equipment to make these sweets, so they were originally quite expensive and eaten only by wealthy people. Later, innovations in manufacturing made both sugarplums and other candies cheaper, and available for consumption by the masses.

In addition to getting a shout-out in The Nutcracker, sugarplums are also famously mentioned in Clement Clark Moore’s anonymously published 1823 poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” better known as “Twas the Night Before Christmas” after its first line.

Posset

Long ago, the English enjoyed a predecessor to eggnog known as posset, a kind of “wine custard” made from hot milk curdled with hot ale, wine, or sherry, and mixed with sugar and spices. The drink remained common from the Middle Ages until the early 19th century; over time, it disappeared from the culinary landscape.

Throughout the centuries, winter revelers enjoyed variations on the recipe, and eggs were eventually added to the mix. But since milk, eggs, and liquors like sherry and Madeira wine were either expensive or hard to come by, the drink’s popularity dwindled among the masses. Meanwhile, in America, early settlers created their own version of posset, which we today know as eggnog.

Animal Crackers

Ever wondered why boxes of Barnum’s Animal Crackers have a string attached to them? According to the most popular story, it was so they could be used as a Christmas ornament. Some doubt that version of events—instead, they say that the handle was there for ease of carrying—but by the 1920s at the latest, Nabisco was definitely advertising that the containers could be festively hung on branches.

A version of this story originally ran in 2019; it has been updated for 2025.