Of the unusual guest requests received by employees of New York’s Hotel Bellclaire, dozens of pounds of raw meat ranked near the top. Nonetheless, the bellhop who was dutifully sent to field the order the afternoon of May 24, 1920, could not have anticipated what awaited behind the door. There, in a posh suite, lounged a very real and presumably very hungry lion.

The bellhop did an about-face and made a mad dash for a supervisor. Authorities were phoned, and soon, a picture emerged. The guest booked in the room had just checked in. He claimed to be a pianist who required heavy instrumental equipment be pulled up via rope to the upper floor. (The actual contents of the box: the lion.) The hotel’s registry listed him as a “Mr. Zann.” Closer inspection revealed initials: T.R.

Whether things clicked in place at once or whether it took them a few moments is unknown. What is confirmed is that a sedated and possibly toothless lion had been smuggled into the Bellclaire by a “T.R. Zann” just as a new film, The Revenge of Tarzan, was due to hit theaters.

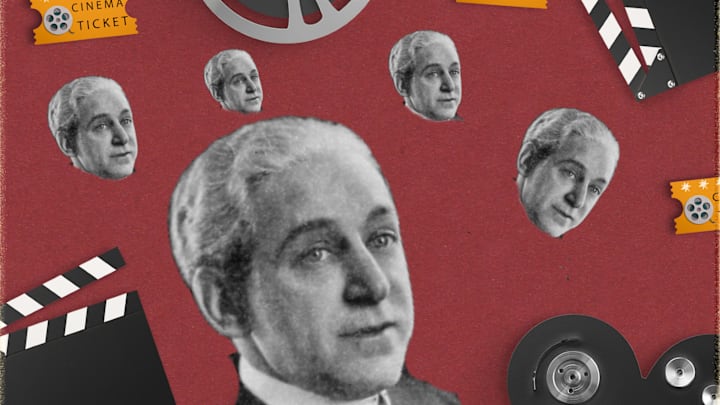

This was hardly a coincidence. The story made headlines, and so did its orchestrator: Harry Reichenbach, a sultan of shameless promotion who would frequently cross boundaries both legal and ethical if it meant drawing attention to a client’s movie or business. Long before marketing campaigns went viral, Reichenbach had mastered the art of subversive publicity, even if it meant being brought before a District Attorney to answer accusations he was a public menace.

The Greatest Showman

The problem with hucksters and carnival barkers is that they’re unreliable narrators—their biographic details should be treated with some measure of suspicion. Harry Reichenbach is no different.

He was (probably) born in 1882 in Frostburg, Maryland, fueled by youthful restlessness that (possibly) led him to run away from home at 13 and join the circus. One early and perhaps apocryphal tale has young Reichenbach noticing a man hefting one brick after another, slowly placing them every few feet and drawing the attention of curious passerby. When enough people had gathered, absolutely befuddled at his intentions, the man hung a poster for an attraction he was promoting.

This kind of marketing showmanship made an impression. Reichenbach once bolstered a restaurant’s business by setting up a water tank in the window and setting up a fan to blow on it. The resulting waves were, he claimed, caused by an exotic “invisible fish.” When Reichenbach got older, he began assisting Maurice Francis Raymond, also known as the Great Raymond, a touring stage magician. The bombast accompanying the illusionist was a perfect training ground for Reichenbach, who demonstrated immense ingenuity in promoting his employer’s act.

While in Rutland, Vermont, for a show, local press caught on to the fact that a girl had been reported missing in a nearby town. Reichenbach quickly approached authorities and raised the possibility of the Great Raymond using his psychic abilities to try and assist in finding her. The police, feeling no harm could be done, agreed.

Reichenbach and Raymond prowled the area, the magician using himself like a divining rod, making sharp turns in the direction of the girl and uttering gibberish as though he were in a trance. She was soon located unharmed, and the press made a fuss of the magician’s clairvoyance. His subsequent shows were sellouts, or close to it.

Reichenbach omitted the fact he had paid the girl’s mother (either $20 or $50, depending on the source) to report the girl missing and that her location was known to him at all times.

The Great Raymond soon ventured to New York. When he packed up, Reichenbach stayed behind. By this point in the early 1910s, stage shows and the nascent film industry seemed to be safer bets for his talents, particularly in the world’s greatest media market. Reichenbach opened an office and hung a shingle.

You Might Also Like ...

- 12 Surprising Facts About Old Hollywood

- Watch Bloopers From the Golden Age of Hollywood

- ‘Colorizers’: When Ted Turner and Hollywood Clashed Over Colorizing Classic Movies

Add Mental Floss as a preferred news source!

What happened next is another story that comes with a heavy asterisk. As Reichenbach told it, he was low on funds for rent and decided to take up with an art dealer who was hoping to sell off his excess stock of 2000 art prints. The copies were of September Morn, a painting by French artist Paul Chabas in which a young girl is depicted wading into a lake, nude.

Reichenbach had perhaps heard of the controversy surrounding September Morn in Chicago and other locations in which local moral authorities condemned it as pornographic. He suggested the art dealer hang the print in his window; Reichenbach then paid a group of children 50 cents each to come and gawk at it as though entranced, their impressionable brains corrupted by the female form.

Reichenbach also placed a call to Anthony Comstock, New York’s vice czar, who frequently monitored the city for any moral lapses. Reichenbach posed as a concerned citizen—something he did often—and implored Comstock to visit the gallery. He did, took note of the assembled children, and began berating the art dealer, insisting it be taken down. The dealer refused. The controversy spilled into newspapers, and the publicity led the gallery to sell its 2000 prints at 10 cents apiece.

September Morn became one of the most infamous artworks of the early 20th century, with prints eventually selling in the millions, but Reichenbach likely exaggerated his contributions to that notoriety.

Exaggeration, of course, is what Reichenbach did best.

At the Movies

Reichenbach’s arrival in New York seemed to coincide with a newfound demand for movie studios to employ publicity specialists to help fuel growth of the motion picture industry. When an actor approached Reichenbach looking to increase his visibility, Reichenbach advised him to walk to his next audition while dropping change out of his pocket. When his prospective employers saw the actor swamped by people, they assumed he had a loyal following. Another actor with the same issue saw Reichenbach enlist a woman to deliver a smoke-filled box to the performer, insisting it was a bomb and she was aiming to blow up her beloved.

Among Reichenbach’s first publicity stunts for a film came in 1915, when he was charged with drawing attention to Trilby, an adaptation of the George du Maurier novel in which a woman is seduced by Svengali. Reichenbach arranged for a woman to run around the block 12 times, sit for the film, and then appear to be in a trance when the character appeared onscreen, as though she were having a visceral reaction (complete with racing pulse) to his hypnotic gaze. Theater workers phoned for an ambulance, at which point she was coherent enough to utter what must have been a Reichenbach-scripted flourish: “Those eyes, Svengali, those eyes—take him away!”

In 1918, Tarzan of the Apes was released. It was the first film based on the Edgar Rice Burroughs character who debuted just a few years earlier in print, and the studio felt it was in need of some advance hype. Reichenbach opted to acquire an orangutan, dress it up in a tuxedo, and set it loose inside of New York’s Knickerbocker Hotel. (No such stunt was executed for the Tarzan sequel, which did not do as well as the original; the third film once again employed Reichenbach, who repeated his animal-in-hotel formula with the lion in residence at the Belleclaire.)

You Might Also Like ...

- Curious Facts About Movies

- 7 Not-Very-Scandalous Retro Hollywood Scandals

- 10 Juicy Facts About Mary Astor’s Purple Diary, Old Hollywood's Most Infamous Sex Scandal

At some point, studios began insisting that Reichenbach assume liability for any humans or animals harmed during such stunts. But his next idea was no less audacious. For 1920’s The Virgin of Stamboul, about a kidnapped girl in Turkey, Reichenbach enlisted 12 men of Turkish descent, outfitted them in regional apparel, and set them loose upon the city, telling hotel employees they were on the trail of a sheik’s daughter who had gone missing. This “Rockefeller of Turkey” was so concerned he was offering a huge cash reward for her safe return. It was a drama even The New York Times picked up without scrutiny.

The exotic nature of the outlandish story ate up newspaper columns, even after one reporter noticed one “Turkish soldier” had an American-made dress shirt in his luggage. The plot was eventually uncovered, but Reichenbach had gotten his movie the attention he had promised.

By this point, Reichenbach was making anywhere from $1000 to $2000 weekly to plot and execute such schemes, which grew increasingly tasteless. In 1920, police discovered a note that appeared to be the last words of a woman visiting New York from Japan, with intimations her body could be found in the Central Park lake. Police combed the water but found nothing.

Soon, New York City’s District Attorney, Edward Swann, settled on Reichenbach as a prime suspect of the hoax. (Conveniently, a film was coming out featuring a Japanese woman who goes missing in New York.) Called in to speak to the DA’s office, Reichenbach denied involvement, though one could hardly blame them for profiling him.

More stunts followed, including a campaign for the Biblical tale The Queen of Sin in which Reichenbach left a wooden model for police to find that was encased in salt, as though some vengeful deity had turned someone into a pillar of the stuff. (An exposed back revealed the wooden framing.)

This time, no one bit, and the pillar of salt went unnoticed by newspapers. By the late 1920s, film publicity was turning a page, with fewer socially-invasive stunts and more of a focus on the lives and dramas of the talking movie stars who had emerged out of the silent film era.

But Reichenbach’s influence lingered. Audiences were left wondering if people were really fainting during screenings of The Exorcist in 1972 or whether the onscreen claim that The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was indeed based on a true story was accurate (it wasn’t). In 1999, pre-release speculation was that The Blair Witch Project was a true documentary, its missing film crew truly lost to a witch of the woods. Surely all of it would have made Harry Reichenbach crack a smile.

Before his death on July 3, 1931, Reichenbach co-authored his memoirs, Phantom Fame. Given his penchant for embellishment, it’s hard to know whether to file it as fiction or non-fiction. A 1932 film loosely based on the book probably said it best. It was called The Half-Naked Truth.