Referring to someone as a “worm” usually expresses a pretty low opinion of that individual. Betrayed at work? Your foe could be a worm. Relationship gone sour? Perhaps you were dating a worm. Yet bookworm is just the opposite. It ascribes complimentary traits to the proverbial well-read larvae in question, including intelligence and a desire for knowledge. So how did bookworm become the exception to the rule?

Initially, it wasn’t. According to Merriam-Webster, the use of bookworm dates to the 1500s when the word was a rather naked insult. A bookworm was someone who was insulated, prone to idle behavior, and failing to make any significant contribution to society. It was not unlike calling someone useless.

Even in the context of being a voracious reader, a bookworm was thought to be someone who lacked discriminating taste. They would read anything, no matter how insubstantial. A window sign in a shop, for example, might prompt the bookworm to stop and stare; an outdated newspaper could provide an hour’s entertainment for the lowly bookworm. They were too consumed by their passion and it was perceived as an unattractive trait. What wretches these despicable people of literacy were.

Bookworms were also perceived as idle, or candle-wasters. One correspondent in the 1500s decried a bookworm as being comparable to a maltworm, or alcoholic.

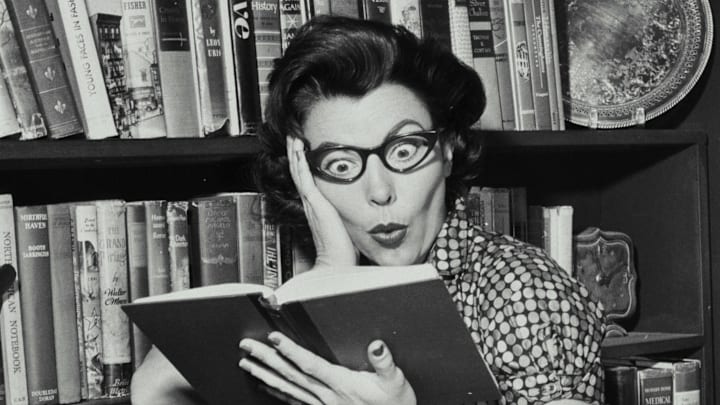

Bookworm as a term of scorn persisted well into the 20th century. “Now, of bookworms there are several sorts,” observed one gleefully cruel 1907 Baltimore Sun column. “There is the lady bookworm known to you by sight. She is the lady of the inquisitive nose and eager eye, whose arm is usually encircling books and whose mind runs to books, not to men. Then there is the male bookworm to whose days and nights books are the one and necessary means of solace [...] thinness and haggard looks mark the true bookworm.”

Curiously, bookworm as an insult predates bookworm as a reference to a literal book-devouring creature. Per The Oxford English Dictionary, insects weren’t labeled as bookworms until the 1600s, when the term came to describe certain species of beetles and moths that dined on paper and binding glue.

It’s difficult to know exactly when the tide began to turn on bookworms, though it’s been a relatively recent development, and one that might mirror the newly-laudatory references to once-derogatory words like geek and nerd. Bookworms, it turned out, held a pretty impressive repository of information. One proponent of the bookworm was Miles Wyatt, a high school student in Port Lincoln, Australia. Wyatt penned the following in a 1947 newspaper:

“Bookworms are among the most despised people on this earth,” he wrote. (This was, we’ll remind you, two years after the horrors of World War II.) “And for what reason? Only that, instead of rushing about in their spare time, they prefer to find a quiet book and, in the common vernacular, ‘bury their heads’ in a book. Truly an outrageous state of affairs!

“[…] I am convinced that the average bookworm who is generally depicted as an embryo genius, professor or scientist, delving into cold matter-of-fact volumes in search of more and yet more knowledge, long-haired and bespectacled, has been grievously wronged. In my humble opinion he is just an ordinary fellow who at times prefers the companionship of a good book by the fireside to that of a noisy crowd […] when next you are about to condemn someone as a bookworm, pause and think a little, and remember that that person is only blessed with a little more curiosity than others, and that you cannot blame him for satisfying that curiosity.”